Stroke & Vascular Disorders

Neoplastic and infectious aneurysms

Dec. 29, 2024

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Worddefinition

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas.

Basilar artery brainstem infarctions are perhaps the most feared and devastating of all ischemic strokes. With the development of advanced high-resolution MRI wall imaging, our understanding of symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic disease has expanded beyond the presence of luminal diameter stenosis. Basilar arterial wall remodeling and symptomatic non-stenosing intracranial atherosclerotic disease (and its significant contribution to embolic stroke of undetermined source) are presented. The latest basilar artery mechanical thrombectomy randomized controlled trial data, bridging intravenous thrombolysis prior to mechanical thrombectomy, intra-arterial thrombolysis, and basilar artery percutaneous angioplasty and stent randomized controlled trial evidence, are discussed.

|

• Basilar artery stroke can be a grave condition. | |

|

• Basilar artery stroke is most commonly caused by atherothrombosis and cardioembolism. | |

|

• Patients with acute ischemic stroke in the basilar artery territory should receive intravenous thrombolytic therapy with tenecteplase or alteplase, even if mechanical thrombectomy is planned. | |

|

• Mechanical thrombectomy has been proven to be beneficial in basilar artery thrombosis. | |

|

• Current evidence does not support the use of percutaneous angioplasty and stent in the intracranial posterior circulation. | |

|

• Arteriographic absence of arterial luminal imaging is no longer the “gold standard” in ruling out symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis. Symptomatic non-stenosing intracranial atherosclerosis appears to play a substantial role in stroke. |

The first clinico-pathologic report of basilar artery occlusion appeared in 1868 by Hayem (80). In 1882, Leyden reviewed prior cases of basilar artery occlusion, reported two additional clinico-pathologic cases of his own, described aneurysmal dilation of the basilar artery, and discussed the differential diagnosis between atherosclerotic basilar artery disease and superimposed thrombosis, embolism to the basilar artery, and syphilitic basilar artery endarteritis with thrombosis (106). His discussion of three patients who presented with sudden (but nonfatal) bulbar signs, presumed to have basilar artery thrombosis, probably represents the first recorded instance of basilar artery stroke. Charles Dana, in an extensive review of infarctions and hemorrhages of the pons and medulla surveyed 39 autopsied cases of lower brainstem infarction and noted that many patients had prodromal transient attacks of hemiparesis, vertigo, dysarthria, and double vision during the months or years preceding their major strokes (43). He divided the clinical presentation into two major categories: (1) long tract motor and sensory dysfunction and (2) bulbar symptoms and signs. Foix and Hillemand published a detailed review of pontine infarcts and the anatomy of the basilar artery and its branches (63).

Kubik and Adams's classic report on basilar artery occlusion in 1946 shaped modern conceptions of pathology and pathogenesis of basilar artery steno-occlusive disease (96). They analyzed 18 necropsy cases, concluding that basilar artery occlusions are characterized by frequent early loss of consciousness, common bilateral involvement, and combinations of pupillary disturbance, ocular and other cranial nerve palsies, dysarthria, extensor plantar responses, hemiplegia or quadriplegia, and often a marked remission of symptoms. Biemond emphasized amnesia, hemianopsia, and other posterior cerebral artery manifestations of basilar artery distribution ischemia (23). Millikan and Siekert detailed vertebrobasilar transient ischemic attacks ("vertebrobasilar insufficiency") and advocated anticoagulants as therapy. Kemper and Romanul described a patient with the loss of the ability to communicate due to limb and bulbar paralysis, a condition later coined "locked-in syndrome." A public light was shed on this rare and devastating disorder with the 1997 publication and film of the same name in 2007, Le Scaphandre et le Papillon (The Diving Bell and The Butterfly) a moving, first-person account by Jean-Dominique Bauby, former Editor-in-Chief of the French magazine Elle and a victim of a basilar artery stroke. The locked-in syndrome had already been depicted in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte Cristo, when he created Monsieur Noirtier de Villefort. Dumas described his character as a “corpse with living eyes” (188). Caplan described the "top of the basilar syndrome” and attributed it to embolic occlusion of the distal basilar artery producing ischemia of the rostral brainstem and the posterior cerebral artery territories (35).

The clinical manifestations of basilar artery ischemia vary according to the site and nature of vascular compromise. Four broad clinical profiles may be distinguished.

Proximal and middle basilar artery occlusive disease. Stenosis or occlusion of the proximal or middle segments of the basilar artery is frequently atherosclerotic in origin. It produces unilateral or bilateral pontine dysfunction and less often cerebellar, midbrain, occipital, or mesial temporal lobe ischemia. The clinical profile of large vessel pontine ischemia is dominated by long tract motor dysfunction, frequent altered consciousness, and disordered horizontal eye movement.

The most characteristic motor manifestation is asymmetric quadriparesis, though hemiparesis, hemiplegia, and quadriplegia can occur. Weakness of bulbar musculature, including the face, pharynx, larynx, and tongue, is frequent and typically bilateral. A crossed pattern of motor deficit occasionally is encountered, for example, simultaneous lower motor neuron left facial weakness and upper motor neuron right arm and leg paresis. Bulbar symptoms include facial weakness, jaw weakness, dysarthria, dysphonia, and dysphagia. Impaired handling of secretions with aspiration is a common complication. The most extreme motor manifestation of pontine ischemia is the locked-in syndrome; this is characterized by complete loss of all voluntary limb and facial movement, with retained consciousness and preserved vertical gaze. Basilar artery thrombosis may also present as a transient locked-in syndrome (64).

Oculomotor signs include a sixth nerve palsy, horizontal gaze paresis, internuclear ophthalmoplegia, the one-and-a-half syndrome (ipsilateral horizontal gaze palsy in one direction of gaze and internuclear ophthalmoplegia in the other), ocular bobbing (rapid downward movement of the eyes with slow return to primary position), horizontal nystagmus, vertical nystagmus, ptosis, and skew deviation. Pupils are often spared, but pinpoint, reactive pupils may be seen in comatose patients with large pontine lesions.

Acutely altered consciousness is present in up to half of patients with proximal-middle basilar artery occlusions. Findings range from mild somnolence to coma.

Less prominent manifestations of proximal-middle basilar artery territory ischemia include limb ataxia, pseudobulbar affect, somatosensory deficits, and hemianopsia. Limb ataxia occurs frequently, is often bilateral, and usually coexists with, but is disproportional to, homolateral weakness. Pathologic crying and laughing appears occasionally. Unilateral or bilateral somatosensory deficits are reported in one-fifth of patients. Occasionally, artery-to-artery embolism from the proximal basilar artery to the posterior cerebral artery produces homonymous hemianopsia, visual agnosia, memory dysfunction, and other features of occipital or mesial temporal lobe ischemia. Basilar artery ischemia can manifest as acute unilateral or, more rarely, bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (91) or rhythmic tonic movements of all the extremities, often mistaken as seizures (155; 189).

Transient vertebrobasilar circulation ischemic attacks precede stroke in about three fourths of infarcts due to proximal and middle basilar artery stenosis or occlusion. Often one or more transient ischemic attacks culminate in infarction over a 3- to 6-month time period. Occasional patients may have transient ischemic attacks alone, or incidental, asymptomatic disease. Infarcts often progress with a stuttering course of stepwise worsening over minutes, hours, or days, although abrupt onset of maximal deficit can occur.

Basilar artery thrombosis may cause auditory hallucinations. Galtrey evaluated a 60-year-old man with episodes of bilateral auditory hallucinations described as “white noise,” which were associated with basilar artery thrombosis and attributed to ischemia of the auditory pathways in the brainstem (65).

Distal basilar artery occlusive disease ("top of the basilar syndrome"). Occlusion of the distal basilar artery is frequently embolic in origin, and produces signs of midbrain and thalamic ischemia, occipital and mesial temporal lobe ischemia, or both.

Infarction of the rostral brainstem and cerebral hemispheres fed by the distal basilar artery causes a clinically recognizable syndrome characterized by visual, oculomotor, and behavioral abnormalities, often without significant motor dysfunction. Leading features of midbrain ischemia are abnormalities of oculomotor and pupillary function and alertness.

Somnolence, vivid hallucinations, and dreamlike behavior can also accompany rostral brainstem infarction. Temporal and occipital lobe infarctions frequently cause hemianopsia with distinctive characteristics, fragments of the Balint syndrome named for the Austro-Hungarian neurologist Rezso Balint in 1909 (a triad of optic ataxia, oculomotor apraxia, and simultanagnosia), amnesia, and agitated behavior. More than three fourths of patients exhibit disruption of voluntary and reflex vertical gaze, rarely selectively affecting upgaze or downgaze but more often disrupting both. Convergence abnormalities are common, most often esotropia at rest or convergence retraction nystagmus (quick phases that converge or retract the eye) on attempted vertical gaze. Bilateral eyelid ptosis and lid retraction occur. Pupils will be fixed and dilated if the third nerve nucleus is compromised. Hypersomnolence may be present at onset, and rarely can persist for months. Ataxia occurs frequently, but hemiparesis is rare. Visual hallucinations, vivid but generally nonthreatening, are infrequently observed ("peduncular hallucinosis") (35).

When ischemia extends to the mesial or anterior thalamus, memory dysfunction, abulia, or both, may appear.

Occipital lobe infarction produces visual field defects, generally homonymous hemianopsia or homonymous quadrantanopsia. Alexia without agraphia may appear with dominant occipital lesions involving the splenium of the corpus callosum. Bilateral lesions may produce other higher visual function disturbances, including cortical blindness, prosopagnosia, visual object agnosia, and Balint syndrome. Mesial temporal lobe infarction can produce memory disturbance, especially if lesions are bilateral (135). Agitated delirium at onset can occur with dominant occipitotemporal infarcts.

Transient ischemic attacks commonly precede strokes when distal basilar artery disease is due to local and upstream atherosclerosis within the vertebrobasilar system, whereas embolism from the heart and ascending aorta usually produces sudden infarcts without warning.

Generalized tonic clonic seizures may rarely be the initial presentation of the top of the basilar syndrome (123).

In 1977, Archer and Horenstein elegantly documented the clinical symptomatology and angiographic findings of 20 patients with basilar occlusions at various sites along the artery and three patients with bilateral vertebral artery occlusions (13). Although the clinical symptoms have been separately discussed in this article, a review of this concise, clinical-radiographic correlation is a useful exercise.

Basilar branch disease. Basilar artery atherothrombosis may occlude the ostium of a penetrating vessel without compromising flow in the basilar artery itself, producing a fractionated ventral pontine clinical syndrome. Ataxia, hemiparesis, and dysarthria in various combinations are common, including syndromes of pure motor hemiparesis, ataxic-hemiparesis, and clumsy hand-dysarthria, which may occur in paramedian pontine perforator occlusions. Either vertigo or diplopia appears infrequently, accompanying mild, transient sensory loss. Occlusion of the thalamogeniculate branches arising from the posterior cerebral artery may produce contralateral subjective sensory symptoms and limb hemiataxia and hemichorea. Occlusion of the thalamoperforating artery branches may produce unilateral or bilateral thalamic infarctions, which may culminate in cognitive dysfunction, somnolence, and aphasia (34).

Basilar artery dolichoectasia (elongation and tortuosity). When the basilar artery becomes markedly widened, elongated, and tortuous, distinctive syndromes related to compression may arise in addition to ischemic syndromes related to abnormal laminar flow causing thrombosis and occasional distal embolism, torsion occluding the origins of small penetrating vessels, and associated intrinsic small vessel disease (45). Cranial nerve compressive signs are present in over half of symptomatic cases, most often hemifacial spasm and trigeminal neuralgia. It can also cause abducens nerve (CN VI) paralysis, and rarely compress the optic tract, accounting for optic atrophy and homonymous hemianopsia. Direct brainstem compression of the ventral pons may produce ataxia and hemiparesis, progressing over months to years. Hydrocephalus may arise and produce gait, bladder, and cognitive abnormalities. Headaches occur in 15%. Almost half of reported symptomatic cases have coexisting or isolated ischemic symptoms, affecting pontine, midbrain, cerebellar, thalamic, or occipitotemporal regions. Subarachnoid hemorrhage can occur infrequently. In younger people, dolichoectasia may be associated with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), Marfan syndrome, Ehler-Danlos syndrome, sickle cell disease, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, neurofibromatosis type I, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, tuberous sclerosis complex, Pompe disease, moyamoya disease, cavernous malformations, and Fabry disease (115; 45). Ischemic symptoms are often attributable to lacunar infarctions. Apart from symptomatic cases, dolichoectatic basilar arteries are often an asymptomatic finding at imaging or autopsy.

Series of patients diagnosed by noninvasive imaging suggest a less ominous prognosis than earlier autopsy and angiographic cohorts, but basilar artery stroke remains a grave condition. One review found that patients presenting with consciousness disorders or the combination of dysarthria, pupillary disorders, and lower cranial nerve involvement invariably had poor outcomes compared to only 11% of patients without these signs (49). In addition, patient age and comorbidity, the size of infarct, and whether the vascular lesion is stenotic or totally occlusive are major determinants of outcome.

Prospective data on acute outcome from basilar artery stroke are sparse. In the New England Medical Center Registry series of 87 patients with severe basilar artery occlusive disease, only 2.3% of patients died of their acute stroke. At hospital discharge 40% had no neurologic deficit, whereas residual deficits were minor in 31%, and severe in 26%. Predictors of poor outcome included distal territory involvement, embolism, occlusion, impaired consciousness, tetraparesis, and abnormal pupils. Similarly, in a series of 27 patients with top of the basilar stroke, only 4% died within the first 30 days (131).

The typical course of basilar artery occlusions is more devastating than basilar artery stenoses. Angiographic series have reported mortality in 80% to 90% of patients. (99; 78; 57). Other studies suggest a less grim prognosis, especially in patients with atherothrombotic occlusions of only a short basilar segment and good collateral supply (98; 29). Endovascular therapy may improve the outcome of acute basilar artery occlusion.

There is a paucity of long-term follow-up information regarding patients who suffer from locked-in syndrome. Five-year survival rates have been estimated to be 80%, and some patients have been reported to live for more than 20 years. In an attempt to further understand locked-in syndrome, 44 patients surviving an average of 62 months following onset of locked-in syndrome were surveyed (103). Attention level was described as good by 86%, and 77% were able to read. A majority (85%) characterized themselves as being more emotional than before their stroke, and 48% reported a good mood. Although communication is difficult for patients with locked-in syndrome, 66% could communicate without technical aids using a system of eye movements and blinking, and 78% were capable of emitting sounds. This survey highlights the importance of multidisciplinary treatment of patients with locked-in syndrome in order to maximize their abilities. In another study of 67 patients with locked-in syndrome for a median of 7 years, including 51 due to stroke, self-reported quality of life survey results were relatively satisfactory compared to those with other severe conditions. Satisfaction persisted during a 6-year follow-up interval. However, those whose communication was limited to yes-no code rather than an electronic communication device reported lower satisfaction (152).

Patients with basilar artery embolism with spontaneous dissolution may fare better than those with persistent occlusion. In a study of patients with presumed basilar artery embolism without occlusion, 42% had no or only mild neurologic deficits 8 to 12 weeks after stroke onset, and 18% died (161).

The long-term risk of recurrent transient ischemic attack or stroke after first ischemic presentation of basilar artery disease is poorly defined. Anecdotal clinical experience suggests that intrinsic atherothrombotic disease is attended by frequent subsequent transient ischemic attacks or recurrent strokes. In the Oxford Vascular Study, the 90-day risk of recurrent stroke or transient ischemic attack was 46% for patients with greater than or equal to 50% basilar or vertebral artery stenosis (122). Distal basilar artery low flow status as measured by quantitative MRA in patients with at least 50% symptomatic stenosis of the vertebral or basilar arteries within the preceding 60 days is strongly associated with subsequent stroke risk (10). Moreover, despite the overall increased stroke risk with higher blood pressure in patients with intracranial stenosis, blood pressure 140/90 mm Hg or lower may increase the stroke risk in patients with symptomatic vertebrobasilar stenosis and low-flow status (11). Advancements in intracranial high-resolution MRI arterial wall imaging can demonstrate “active” culprit plaques that have been symptomatic with recent infarction as well as presymptomatic active plaques.

Nearly half of patients with basilar artery dolichoectasia deteriorate clinically over 5-years (194). Infarction (18%), transient ischemic attack (10%), compressive symptoms (10%), intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage (6%), and hydrocephalus (3%) account for the clinical deterioration (45). Those with large, bilateral pontine infarcts related to basilar artery occlusion almost uniformly experience poor outcomes. Those with smaller, unilateral pontine infarcts, likely due to obstruction of the origin of a pontine penetrator or associated intrinsic small vessel disease, have a more favorable early outcome. The long-term course is poor, with up to one third of patients dying within 5 years, often from recurrent stroke (125). Symptomatic initial presentation, dolichoectasia severity at diagnosis, worsening angioarchitecture during follow-up and mural thrombus, contribute to delayed morbidity. Radiographic progression occurs in 42%.

Complications of basilar artery stroke include aspiration, dysphagia requiring G-tube or J-tube placement, urinary tract infection, pressure ulcers, and venous thromboembolism.

Vignette 1. A 65-year-old man with arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and coronary artery disease, was admitted with transient dysphagia, dysarthria, binocular diplopia, and impaired consciousness from which he markedly improved on arrival to the emergency room. He had mild dysarthria on examination at 1 hour after fluid resuscitation and blood pressure support for hypotension, which was thought to be responsible for his presentation.

A code was called later the first night of admission (12:34 am) at which time he was found unresponsive and profoundly hypertensive, tachycardic, and tachypneic.

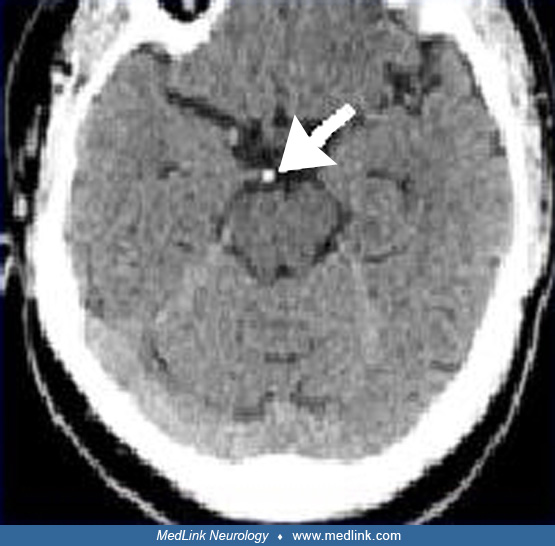

The patient was intubated and transferred to the intensive care unit on intravenous antihypertensive agents. Evaluations for cardiac etiology and pulmonary embolism were unremarkable. Neurology consultation was obtained when patient examination did not improve by the morning. MRI of the brain demonstrated restricted diffusion in the pons. MRA demonstrated thrombus in the mid-basilar artery. Endovascular treatment was unsuccessful. The patient remained in a “locked-in” state and mechanical ventilation was eventually withdrawn at his own wish.

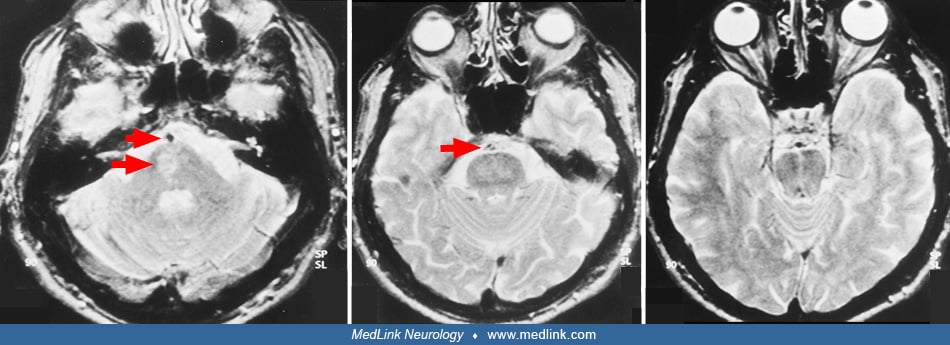

Vignette 2. A 65-year-old woman presented with acute onset ataxia, headaches, bilateral arm numbness, and binocular diplopia. Examination was remarkable for decreased alertness, bilateral sixth nerve palsies, and bilateral upper limb dysmetria. Further deterioration in her level of consciousness prompted an acute CT without contrast, which was normal. MRI showed restricted diffusion in bilateral thalamic, bilateral cerebellar, and right midbrain regions. Presentation after 3 hours prompted catheter cerebral angiography where basilar artery thrombus superior to the anterior inferior cerebellar artery branches was demonstrated. Intraarterial tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in combination with MERCI (Mechanical Embolectomy Retrieval in Cerebral Ischemia) retriever restored flow to the remainder of posterior circulation with good clinical outcome. (Courtesy of Dr. Tim Malisch and Dr. José Biller.)

Vignette 3. An 81-year-old woman with arterial hypertension and a left middle cerebral artery bifurcation aneurysm was evaluated at an outside hospital for nausea, dysarthria, headache, and dizziness. She was intubated after exhibiting decreased alertness in the emergency department. Gaze-evoked nystagmus, decreased arousal, and inability to follow commands were noted on examination prior to intubation. She was transferred to our institution for further evaluation and management. MRI and MRA showed right cerebellar, midbrain, bilateral occipital, and pontine tegmentum infarcts from proximal basilar artery thrombosis. (Courtesy of Dr. José Biller.)

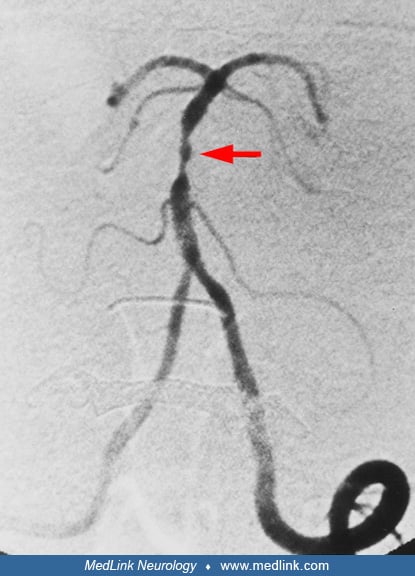

Vignette 4. A 51-year-old man was evaluated for transient quadriparesis and dysarthria. At the time of examination, the patient was asymptomatic with unremarkable neurologic exam. He had a history of prior transient right hemiparesis. Diffusion-weighted MRI showed no acute lesion. MRA demonstrated moderate to severe midbasilar artery stenosis. Catheter cerebral angiography showed a 65% to 70% midbasilar stenosis with poststenotic dilatation above the level of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery and below the labyrinthine arteries. (Courtesy of Dr. José Biller.) The patient was placed on antiplatelet and statin therapy.

Vignette 5. A 69-year-old man with diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, and a previous stroke was found unconscious at home. He was last known to be well 8 hours before. His trachea was intubated on the scene by Emergency Medical Services and he was taken to the emergency department. Initial neurologic exam was confounded by residual pharmacologic paralysis and sedation used for intubation. Emergent CT showed a midbasilar hyperdensity suggesting thrombus and MRI demonstrated restricted diffusion in bilateral cerebellar, bilateral thalamic, and bilateral occipital regions. Follow-up examination showed impaired consciousness, bilateral decerebrate posturing, bilateral nonreactive pupillary reflex, bilateral absent corneal reflex, absent eye movements with oculovestibular reflex testing, and preserved gag reflex.

Vignette 6. A 70-year-old man with a past history of trigeminal neuralgia awoke with dysarthria, left hemiplegia, and nausea. Examination also revealed horizontal and vertical nystagmus, skew deviation, and hoarse voice. Noncontrast brain CT showed hyperdensity anterior to the pons consistent with dolichoectasia of the basilar artery with acute or chronic thrombus. CT angiography demonstrated dolichoectasia of the basilar artery with occlusion of bilateral vertebral arteries and proximal basilar artery. MRI showed displacement of the brainstem with restricted diffusion in the right pons consistent with paramedian pontine small vessel distribution infarction. Motor examination initially improved to antigravity strength in the left arm and leg. Non-bolus intravenous heparin nomogram was started on hospital day 1 with target aPTT 50 to 70. He was transitioned to subcutaneous enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily on hospital day 2, and warfarin was initiated. On hospital day 4, he became acutely unresponsive, apneic, bradycardic, and pulseless. A code was called, trachea was intubated, and return of spontaneous circulation was achieved. Noncontrast brain CT demonstrated diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurologic examination did not recover, and death was subsequently declared by neurologic criteria.

Atherothrombosis and cardioembolism are the most common causes of basilar artery territory infarctions. Less frequent etiologies include cervicocephalic vertebral artery dissection, migraine, dolichoectasia, hematologic disorders (eg, sickle cell disease, hypercoagulable states), vasculitis, meningovascular syphilis, and paradoxical embolism (124; 196).

The vertebral arteries unite to form the basilar artery at the base of the pons. The vertebral arteries arise from their respective subclavian arteries medial to the anterior scalene muscle. After originating (ie, V1 or first segment) from the subclavian arteries, the vertebral artery traverses the foramina transversaria from C6 to C2 (ie, V2 or second segment), loops around the atlanto-occipital joint (ie, V3 or third segment), and finally pierces the dura passing through the foramen magnum to enter the intracranial cavity (ie, V4 or fourth segment) to join the other vertebral artery at the pontomedullary junction. The V2 segment is further subdivided into proximal V2 segment (C6), mid V2 segment (C2-5), and distal V2 segment (C1-2). The basilar artery ascends in a shallow groove on the anterior surface of the pons, with an average length of 32 mm and width of 2.6 mm to 3.5 mm (157). In most patients, the artery is curved, whereas in one fourth of patients it follows a straight-line rostral course. The basilar artery ends by dividing into the two posterior cerebral arteries in 80% of the population at the level of the interpeduncular cistern. Many variations can occur, including fetal origin of one or both posterior cerebral arteries, a vertebral artery ending as a posterior inferior cerebellar artery, and a persistent trigeminal artery. Thalamoperforating arteries arise near the basilar artery bifurcation and perfuse the medial and anterolateral thalamus. Thalamogeniculate arteries arise from the posterior cerebral artery and perfuse the lateral thalamus. Asymmetric vertebral arteries are found in over two thirds of cases. Throughout its rostral course in the middle third, the basilar artery gives off approximately 14 small paramedian branches that penetrate directly into the ventral pons and lower midbrain, and 14 small circumferential arteries that loop around the pons and midbrain to give off lateral basal and lateral tegmental penetrators (153; 133).

The major branches of the posterior circulation include the paired posterior inferior cerebellar arteries, which arise from the V4 segment and can have intra- or extradural origins in some cases. Paired anterior inferior cerebellar arteries arise next from the more proximal basilar artery. Distal paired superior cerebellar arteries arise last, prior to the basilar artery termination into bilateral posterior cerebral arteries, and serve the superior cerebellum. Clinically, superior cerebellar artery territory infarcts can potentially interrupt Mollaret’s triangle and cause palatal tremor (myoclonus).

The pons is a knob-like process measuring approximately 2 cm in length. It is organized into white matter tracts that travel transversely whereas most other fibers in the brainstem travel rostral and caudal. The posterior surface of the pons forms the anterior wall of the fourth ventricle. The pons may be further subdivided into the basis pontis and pontine tegmentum.

The basis pontis or anterior portion of the pons houses the corticospinal tracts and the nuclei of cranial nerves V, VI, VII, and VIII. The mid-pons houses the motor nucleus and chief sensory nucleus of cranial nerve V. The lower pons houses the cranial nerve nuclei VI, VII, and VIII. Corticopontine fibers carry signals from the primary motor cortex to the ipsilateral pontine nuclei in the anterior pons. Pontocerebellar fibers then relay information to the contralateral cerebellar hemispheres, allowing action modification and correction in complex motor activities. The pons also controls arousal and regulates respiration. The pontine tegmentum located more posteriorly is involved in sleep and wakefulness and is postulated to be involved in initiation of REM sleep. It contains the richly serotonergic raphe nucleus and locus coeruleus, a norepinephrine-producing area involved in stress response and anxiety. Tegmental lesions in various models can reduce or eliminate REM sleep and dreaming.

Basilar artery fenestration (BAF), considered an anatomic variant, has been reported in association with arteriovenous malformations and developmental arterial anomalies (16). Basilar artery fenestration has a reported prevalence of 1.5% and may play a role in basilar aneurysmal formation and basilar artery thrombosis (20).

Atherothrombotic disease is the most common cause of basilar artery strokes. In a series of 87 consecutive cases of basilar artery ischemia, atherothrombotic disease accounted for approximately 86% (184). Among intracranial vessels, the basilar artery is a frequent site of atherosclerotic change. The middle and proximal thirds of the basilar artery are more susceptible than the distal segment, but the difference is slight. In a review of 412 reported cases of basilar artery atherostenosis, the middle portion was involved in 56%, the proximal in 48%, and the distal in 40% (36). Patterns of vessel injury included atherosclerosis confined to the basilar artery, complex plaques arising in a distal intracranial vertebral artery extending into the basilar artery, and diffuse, disseminated vertebral and basilar artery atherosclerosis.

The 1991 TOAST criteria classified ischemic stroke as due to intracranial atherosclerosis if the luminal diameter stenosis was greater than 50% and without other causes. Following advances in high-resolution MRI vessel wall imaging, clinically significant non-stenosing atherosclerotic plaque can rupture, producing artery-to-artery embolization. This has been increasingly observed and is currently considered to be one of the major causes of embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) (51).

Symptomatic non-stenosing intracranial atherosclerosis is considered one of the most significant etiologies for ESUS. Recurrent transient ischemic attack or acute ischemic stroke in the same vascular territory should raise suspicion of a symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic plaque. Stroke recurrence with intracranial atherosclerosis is estimated to be 15% in 1 year. When including non-stenosing intracranial atherosclerosis, it increases to 25% in 1 year. This emphasizes the need to determine the risk of artery-to-artery embolization by assessing high-risk plaque features (44).

Vessel wall remodeling. Intracranial arteries with atherosclerosis may develop luminal narrowing without enlargement of the atherosclerotic lesions. Many vessel wall plaque segments display compensatory enlargement, which may or may not prevent luminal narrowing. Two forms of vessel wall remodeling have been described. Positive remodeling is consistent with vessel enlargement. Negative remodeling produces vessel and luminal narrowing. Positive remodeling is associated with increased lipid-rich plaque, which increases the risk for plaque rupture (120).

The basilar artery has a greater capacity for positive remodeling, with increasing plaque burden in comparison to the anterior circulation. Suspected mechanisms include the markedly slower blood flow in the basilar artery compared to the anterior circulation, which may impose different endothelial stress on the vessel wall. The relatively sparse sympathetic innervation in the vertebral and basilar arteries in comparison to the anterior circulation make autoregulation less robust, with the potential for arterial dilatation and remodeling (145).

Many of the studies imaging intracranial atherosclerosis using high-resolution MRI vessel walls compared the suspected culprit plaque with an adjacent reference area of vessel appearing to be normal. One of the few studies to longitudinally follow the same intracranial atherosclerotic plaque segment over time revealed that diabetes and wall contrast enhancement were significantly associated with advancing plaque progression, almost 11% in 1 year (75). This produced a 6.6% decrease in luminal area and 6.7% increase in wall thickness.

Plaque enhancement, intraplaque hemorrhage, plaque surface irregularity, degree of stenosis, plaque burden, and positive vessel remodeling were predictors of symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis. Plaque enhancement was the most significant of all the biomarkers for demonstrating culprit plaque in downstream infarctions (167; 84).

Plaque enhancement. Abnormal plaque MRI contrast enhancement is considered a high-risk marker for future stroke in the same vascular territory, both with and without hemodynamically significant luminal diameter stenosis. Although most intracranial arteries do not have a vasa vasorum, neovascularization of inflammatory atherosclerotic plaque may produce gadolinium leakage and enhancement. A 2016 meta-analysis of predominantly anterior circulation infarctions performed high-resolution vessel wall MR-detected plaque enhancement in the intracranial internal carotid artery or middle cerebral artery within 30 days of the index stroke (76). Plaque enhancement was strongly associated with downstream acute infarction. An infarction was 10 times more likely in tissue supplied by the enhancing artery than a non-enhancing artery.

Significance of the atherosclerotic plaque location within the basilar artery wall. High-resolution MRI wall imaging of the basilar artery within 48 hours of symptom onset in patients with normal-appearing basilar artery on MRA revealed that 60% of the vessels demonstrated non-stenosing atherosclerotic wall plaque; 58.3% of those plaques were located along the dorsal or dorsolateral surface of the basilar artery in the expected location of the origin of penetrating branch arterioles, on the same side and axial image as the acute infarction (41). These findings were significant for branch vessel atheromatous disease and were associated with neurologic deterioration and worsened functional outcome.

Basilar artery tortuosity may be associated with atherosclerotic plaque, which tends to form on the inner arc of the tortuous vessel and is more likely to produce positive vascular remodeling of the artery, greater plaque burden, and plaque enhancement (203).

A systematic review of 21 studies of patients with acute and subacute ischemic infarction found that although there was no MRA evidence of hemodynamically significant stenosis as defined by either no stenosis or less than 50% arterial luminal diameter stenosis, MRI arterial wall imaging demonstrated that over half of these patients had atherosclerotic plaque without significant luminal stenosis in the vascular distribution of the infarction (186). Furthermore, radiographic markers that these were active, culprit plaques included intra-plaque hemorrhage, positive arterial wall remodeling, and plaque surface irregularity. Intraplaque hemorrhage was the strongest independent marker of a symptomatic state, with an odds ratio of 27.5. The prevalence of intraplaque hemorrhage did not significantly differ between low- and high-grade stenotic plaque. Low-degree stenosis in the basilar artery was more prevalent than in the middle cerebral artery (63.1% versus 45.4%, respectively) due to the greater capacity for positive (ie, outward) remodeling of the basilar artery wall from atherosclerosis and decreased sympathetic innervation. Suspected infarction mechanisms include artery-to-artery embolization from plaque rupture and plaque-related occlusion of arterial branch vessels.

MRI vessel wall imaging may assist in detecting response to treatment and predict stroke recurrence following intracranial atherosclerotic-mediated stroke.

Song and colleagues demonstrated a combination of atherosclerotic culprit plaque enhancement at the time of the index stroke, and the magnitude of collateral vessels was associated with a higher incidence of stroke recurrence (20% of 60 study patients, p < 0.05) (168).

In a small retrospective study of 29 patients (reduced from 40 patients following exclusion criteria) 3D MR vessel wall imaging was performed within 8 weeks of ischemic stroke onset and subsequently repeated 3 to 18 months after stroke onset (193). Arterial luminal stenosis greater than 50% of the major intracranial artery in the ischemic territory and at least two atherosclerotic risk factors were required. Patients were divided into recurrent and nonrecurrent stroke groups. All were treated with antiplatelet and intensive lipid-lowering therapy. There was no significant difference in the plaque features in baseline scans between the two groups. Of the plaque morphological features analyzed (degree of stenosis, plaque burden, intraplaque hemorrhage, and plaque enhancement ratio), patients with no stroke recurrence had improvement in all of the aforementioned parameters. In patients with recurrent stroke in the same vascular territory, there were statistically significant increases in the plaque wall contrast enhancement, the maximal ratio of wall area to vessel area, and the magnitude of plaque enhancement. The radiographic differences between patients without and with recurrent stroke in this small study demonstrated that MR vessel wall imaging may lead to the identification of patients who may not be responsive to a prescribed medical therapy, which may lead to modification of treatment type or duration.

Lv and colleagues found the risk of stroke recurrence to be significantly increased with increasing plaque burden, degree of stenosis, and contrast enhancement (119).

Stroke mechanism cannot be accurately assessed without visualization of the intracranial arterial walls and characterization of plaque properties (186). Approximately half of acute and subacute ischemic stroke patients with non-stenotic intracranial MRA have identified plaques on vessel wall MRI. Approximately half of acute and subacute ischemic stroke patients with clinical intracranial atherosclerosis have less than 50% stenosis on MRA. Intracranial high-risk plaque with zero or a mild degree of stenosis is associated with ischemic stroke and multiple unfavorable outcomes. Vessel wall MRI can identify the high-risk plaque features and better risk stratify stroke patients.

MRI techniques. 3D black-blood variable-flip-angle intracranial vessel wall MRI can perform whole-brain vessel imaging with higher spatial resolution, greater signal-to-noise ratio, and the ability to reformat in multiple planes. It is superior to conventional 3D time-of-flight MRA and contrast-based CTA in detecting symptomatic plaque, active inflammatory plaque, and plaque length, especially in the posterior circulation. There is greater sensitivity to detect culprit plaque not seen with other conventional imaging as well as plaque showing contrast enhancement consistent with active inflammation, which increases the likelihood of a recurrent infarction (176).

MRA techniques. 3D 5T time-of-flight MRA is superior to demonstrating small intracranial branch arteries in comparison to 3T time-of-flight, with comparable image quality to 7T (162).

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) techniques. 4D-DSA applies a reconstruction algorithm to three-dimensional time-resolved digital subtraction angiography, which allows significantly greater small vessel spatial resolution, can be reconstructed in any plane, and allows quantification of vascular flow. In addition to providing significant presurgical detail for the management of intracranial arteriovenous malformations and fistulas and intracranial aneurysm, there is potential utility for the evaluation of basilar artery occlusive disease and assessment of perforating and collateral vessels (56).

Radiomics in the assessment of symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic plaque. With advances in computer processing power and the development of artificial intelligence modeling, early research in the emerging field of radiomics has demonstrated enhanced ability to detect culprit intracranial atherosclerotic plaque likely responsible for acute ischemic stroke and vulnerable unstable plaque (especially in non-stenotic vessels) for personalized prediction of stroke recurrence. Radiomics in high-resolution MRI vessel wall imaging analyzes features of signal intensity, texture, and spatial orientation within a specified field-of-view. These quantitative high-dimensional mineable features use machine learning to process complex relationships amongst a large number of variables. Radiomics has the potential to enhance detection of abnormalities and differentiate between symptomatic and asymptomatic intracranial arterial plaque beyond the thresholds detected by human direct visualization. Beyond the qualitative detection of the aforementioned parameters that current radiographic interpretation provides, radiomics has the benefit of identifying quantitative variables to enhance accuracy. Three circumstances in which machine learning of signal quantification may provide benefit are establishment of prognosis, future infarction risk, and tailored therapies. Intraplaque hemorrhage signal changes can quantify volume, shape, signal intensity, and proximity to the arterial wall. Secondly, pre-contrast T1 wall hyperintensity may represent intraplaque hemorrhage, and low T1 pre-contrast signal may represent lipid core. Post-contrast T1 hyperintensity may be caused by contrast enhancement of the fibrous cap or vasa vasorum. Thirdly, machine learning analysis of combined radiographic and clinical data can predict preoperatively poor functional outcome following basilar artery thrombectomy. Machine prediction models exceeded traditional scoring systems, such as Brain Stem Score, pc-ASPECTS, and NIHSS (41; 164; 203; 108; 174; 117).

In 1971, C Miller Fisher and Louis Caplan were the first to report their autopsy findings of atheromatous plaque in the basilar trunk, which occluded the ostia of a dorsal wall paramedian perforating arteriole producing a deep pontine infarction (60). The concept was further discussed by Caplan in 1989 (34). These observations expanded the etiology of deep pontine infarctions beyond hypertensive-mediated lipohyalinosis and may also be responsible for some occlusions of the thalamogeniculate, thalamoperforating, and short circumferential basilar artery branches.

Hemodynamically significant atherosclerotic stenosis of the basilar artery lumen is not needed to occlude the ostia of penetrating arteries. Basilar perforating artery origin occlusion should be suspected if there are no vascular risk factors for lacunar disease, especially hypertension.

In 2005, Klein and colleagues reported the first high-resolution MRI vessel wall imaging of basilar artery atherosclerotic plaque in the context of a normal appearing basilar artery lumen. Over 75% of their patients demonstrated non-stenosis plaque (93). Their technique was further refined in 2010 using black blood imaging sequences for high-resolution MRI vessel wall imaging, proving that small deep pontine infarctions not reaching the pial surface originally considered to be lacunar may also be caused by branch vessel occlusive disease from non-stenosing basilar artery plaque (94). Further discussion of intracerebral high-resolution MRI while vessel imaging is described in the Diagnostic Workup section.

Embolism to the basilar artery is the second most common cause of basilar artery territory strokes, responsible for 14% of cases in one series (184). Emboli lodging in the basilar artery generally produce acute occlusion rather than stenosis. Origins for the emboli include the heart, atherosclerotic lesions of proximal extracranial and intracranial vertebral arteries, proximal subclavian arteries, the aortic arch, and vertebral artery dissection. Because the width of the basilar artery narrows as it courses distal, most emboli small enough to pass through the vertebral arteries will traverse the proximal basilar segment and occlude the middle or distal segments.

High-resolution cerebral MRI wall vessel imaging has demonstrated unstable active, inflammatory atherosclerotic plaque that does not have to demonstrate significant luminal diameter stenosis to become symptomatic with plaque rupture and embolization. High-risk MRI features include lipid-rich necrotic core, intraplaque hemorrhage, gadolinium contrast enhancement that may be consistent with neovascularization and vessel leakage, thin fibrous cap, and ulcerations. Embolization from an active non-stenotic cerebral atherosclerotic plaque is considered one of several major causes of embolic stroke of undetermined source (51).

Cervical spine surgical interventions including reduction of cervical spondylolisthesis can rarely result in distal vertebrobasilar embolization (179).

The basilar artery and the distal vertebral arteries, along with the internal carotid arteries, are particularly susceptible to a dilatative arteriopathy, producing vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia (dolichos meaning “long”, ectasia meaning “distended”), also called “fusiform aneurysm” (115). Its prevalence ranges between 0.05% and 18%. Various theories for the development of basilar and carotid dolichoectasia have been advanced, including congenital defects of the media or fragmentation of the internal elastic laminae; and unrecognized preceding arterial dissection with formation of dissecting aneurysms (12). Some or all of these mechanisms likely operate together to account for most cases. Although atherosclerosis can be found within dolichoectatic vessels, atherosclerosis is associated but not primarily causative. Both conditions can coexist. However, data from high-resolution MRI vessel wall imaging in 34 patients with vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia (22 with stroke, 12 without) demonstrated that stroke occurs more commonly in vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia with an associated atherosclerotic plaque (54.5% versus 8.3% in patients without stroke). The degree of basilar artery luminal diameter stenosis and arterial wall remodeling were lower in the stroke group, suggesting that hemodynamic insufficiency is not a cause for stroke. Rather, infarction was suspected due to occlusion of the ostia of perforating arterioles and plaque vulnerability with artery-to-artery embolization. Slow flow within the dilated segment may result in intraluminal thrombus (190). In a study of 719 consecutive patients evaluated for stroke, 238 (33%) demonstrated basilar artery dolichosis, of which 12 (1.7%) patients demonstrated basilar artery dolichoectasia (33). There was increased incidence of stroke in the dolichoectatic versus dolichosis population. Diabetes and smoking, risk factors for intracranial atherosclerosis, are also observed in basilar artery dolichosis. This may exacerbate the development of coexisting atherosclerosis and increase stroke risk. Arterial wall remodeling can occur. Direct compression on the pons and cranial nerves may occur. On rare occasion, there may be vessel rupture producing subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Bow hunter syndrome is a rare condition whereby lateral head rotation produces symptoms of vertebrobasilar ischemia by mechanical compression of a vertebral artery. The term was coined by Sorensen in 1978, who described a patient who developed a Wallenberg syndrome during archery practice (169). Symptoms include syncope or presyncope, vertigo, diplopia, nystagmus, hemiparesis, paresthesias, nausea and vomiting, Horner syndrome, dysphagia, and headache. Symptoms may be transient or persistent due to ischemic stroke in cases of sufficient hemodynamic compromise or formation of thromboembolism.

A case series of 11 patients diagnosed by dynamic catheter-directed vertebral angiography over 14 years at a tertiary referral center reported that the level of vertebral artery compression was most commonly C1-2 and C5-7, with a slight predilection for the left vertebral artery (200). In the same study, the direction of head rotation did not predict the laterality of the compressed artery; 55% of patients had compression contralateral to head rotation, whereas 45% had ipsilateral symptoms. Surgical decompression may be beneficial in alleviating symptoms, although clinical trial data are lacking.

Rare causes of basilar artery thrombosis include meningovascular syphilis, Behçet disease, antiphospholipid syndrome, meningitis, giant cell arteritis, and neuroborreliosis. Back and colleagues reported 11 patients with neuroborreliosis-associated cerebral vasculitis (17). Eight cases involved the vertebrobasilar circulation, and two had basilar artery thrombosis.

Posterior circulation infarcts represent 12% to 27% of all strokes in hospital-based registries, and basilar artery disease accounts for a substantial proportion of these (26; 27). Among 520 consecutive patients with posterior circulation ischemia in three series, basilar artery stenosis or occlusion was responsible for 20% (25; 36). These data suggest that basilar artery stenosis or occlusion is responsible for approximately 4% of all infarcts.

Well-established systemic vascular risk factors strongly influence the development of atherosclerotic change. In the New England Medical Center series of 66 consecutive patients with basilar artery atherostenosis, hypertension was present in 64%, diabetes in 36%, tobacco use in 35%, hyperlipidemia in 35%, coronary artery disease in 45%, and peripheral vascular disease in 20%. Affected individuals tend to be over the age of 50, and more men are reported than women. People of African descent, and possibly those with Asian ancestry, have a predilection to stenosis in more distal segments of the basilar artery, whereas Caucasians are predisposed to stenosis in more proximal segments (72; 36).

Atrial fibrillation was previously considered to be the most common risk factor for cardioembolism to the basilar artery. Currently, artery-to-artery embolization from ruptured non-stenosing intracranial atherosclerotic plaque may play an even more significant role. Valvular disease, left ventricular dysfunction, and patent foramen ovale are also important. Acute basilar artery occlusion is an infrequent complication of cardiac papillary fibroelastoma (113; 51). Other cardioembolic sources include myxoma, papillary fibroblastoma, mural cardiac thrombi, and both infectious and nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis.

Dolichoectasia of the basilar artery is increasingly encountered. Older autopsy and angiographic series of consecutive cases estimated an incidence greater than 0.1% (83; 81; 198). An MRI study identified dolichoectatic vertebrobasilar arteries in 0.9% of 1416 consecutive patients (160). However, in clinical series of patients with posterior circulation ischemia, vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia is present in 3% to 14% of cases (25; 36). In a population-based study of patients with first ischemic stroke, 2.5% had a dolichoectatic basilar artery (87). In a multiethnic study of stroke-free patients older than 55 years, at least one dolichoectatic intracranial artery was found in 19% (77). Risk factors for dolichoectasia of the basilar artery include increasing age and male sex, with an average age at diagnosis of 59 years, and men accounting for approximately 70% of reported cases (105). Risk factors for stroke occurrence include more severe ectasia and vertical elongation and superimposed atherosclerosis (139).

Primary prevention of atherosclerotic disease of the basilar artery includes long-term control of established vascular risk factors. Tobacco abstinence and management of arterial hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia as well as dietary modification should be pursued according to standard guidelines. Primary prevention of cardioembolism to the basilar artery should also follow standard guidelines. In patients with atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation with warfarin with a target international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 or a direct oral anticoagulant such as a direct thrombin inhibitor or anti-Xa agent should be employed if the patient has no major contraindication to anticoagulation and if there is also a history of hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, prior transient ischemic attack or stroke, or if the patient is over age 75. Younger patients with lone atrial fibrillation may adequately be treated with aspirin at a dose of 325 mg daily.

Basilar artery disease is most closely mimicked by other illnesses that cause brainstem pontine dysfunction. These include brainstem encephalitis, demyelinating disease, central pontine myelinolysis (osmotic demyelination syndrome), and basilar migraine.

Basilar artery stroke can also mimic a host of other conditions, leading to a missed diagnosis of basilar artery stroke. These include other causes of acute coma or depressed levels of consciousness. Distal basilar artery occlusion may result in top of the basilar syndrome, which can present with acute neuropsychiatric abnormalities, including visual disturbances and hallucinations that may be confused with psychiatric disease. Basilar artery occlusion may present with rhythmic movements of the extremities mimicking convulsive seizures (189). Clues to basilar artery ischemia include abrupt onset, the presence of a Parinaud syndrome, Collier sign (retraction and elevation of the eyelids), pupillary abnormalities indicating midbrain involvement, and vertical gaze paresis.

Infectious rhombencephalitides tend to have slower onset over hours to days, be accompanied by fever, follow infectious exposures, and have a marked cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis. Multiple sclerosis tends to have slower onset over hours, history of prior lesions disseminated in time and space, lesions confined to white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid positive for oligoclonal bands, and elevations in IgG synthesis and index ratio. The clinical differentiation of both disorders from basilar artery ischemia is sometimes challenging as basilar artery atherosclerotic disease produces abrupt, maximal onset of deficits less often than ischemia at other sites, and a stuttering, progressive course over hours to days is not unusual. Central pontine myelinolysis tends to follow episodes of rapid correction of hyponatremia or other systemic illness and produces bilateral tegmental lesions not fully respecting vascular territory boundaries. Migraine with brainstem aura (previously known as basilar-type migraine) tends to occur in younger adults, often children, and usually produces transient episodes of posterior circulation territory dysfunction (dysarthria, vertigo, diplopia, ataxia, tinnitus, visual symptoms, simultaneous bilateral paresthesias, decreased level of consciousness, etc.) lasting 20 to 30 minutes. The diagnostic picture can be mixed as migraine can rarely be associated with basilar artery stroke, and ischemia related to basilar artery disease can precipitate headaches.

Acute peripheral nerve demyelination and neuromuscular junction defects, such as Miller Fisher syndrome, botulism, and myasthenic crisis, respectively, can mimic symptoms of basilar artery occlusion (114).

Occasional patients with bilateral intracranial vertebral artery stenosis will experience pontine ischemia due to hemodynamic impairment or artery-to-artery emboli, mimicking intrinsic basilar artery disease.

Additionally, a number of other metabolic or systemic etiologies for basilar stroke must be considered. These include trauma leading to vertebral or basilar pseudoaneurysm or dissection with subsequent thrombus formation, cardioembolic sources, vasculitides, hypercoagulable states, Fabry disease, and sickle cell disease. Screening may involve rheumatologic investigation including sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, antiphospholipid syndrome panel, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, ANCA, CSF analysis, or more detailed hypercoagulable studies.

Analysis of clinical features of patients who present with posterior circulation ischemia show commonality with unilateral limb weakness (81.9%), central facial palsy (61.1%), dysarthria (46.3%), and dizziness (33.8%) (163). The incidence of crossed paralysis was relatively low (2.8%).

Pontine syndromes as rare as inappropriate laughter or “fou rire prodromique” have been described, as well as anosognosia for hemiplegia, blepharospasm, brief jerking movements, jaw dystonia, bilateral deafness, trunk ataxia without limb ataxia, hypoesthesias, painful Horner syndrome, sleep disturbances, and trigeminal neuralgia (30).

|

Symptoms and signs |

Vertebrobasilar artery territory |

|

Motor deficits |

Unilateral, bilateral, or shifting limb weakness; limb clumsiness or paralysis; ataxia, imbalance, or disequilibrium with or without vertigo |

|

Sensory deficits |

Unilateral, bilateral, or shifting limb numbness, sensory loss, or paresthesias |

|

Speech deficits |

Dysarthria* |

|

Visual deficits |

Binocular diplopia, partial or complete blindness in both homonymous visual fields |

|

Adapted from: (30) | |

Diagnostic evaluation is directed toward imaging the brainstem, cerebellum, and occipitotemporal regions to characterize the size and territory of the infarct, exclude stroke mimics, determine the vascular mechanism, and guide therapy.

MRI is the preferred modality for imaging posterior fossa structures. CT can be compromised by beam-hardening artifacts from the skull base. In candidates for treatment with intravenous tPA, CT can be helpful in promptly ruling out an intracerebral hemorrhage. MRI infarct patterns particularly suggestive of proximal-middle large artery basilar disease, rather than penetrator disease, are bilateral infarction in the basal or tegmentobasal pons; bilateral infarction in the brachium pontis (anterior inferior cerebellar artery territory); and upper pontine or midbrain infarction, plus anterior inferior cerebellar artery territory cerebellar or brachium pontis infarction. In patients with top of the basilar lesions, upper pontine or midbrain infarcts may coexist with unilateral or bilateral thalamic and hemispheric posterior cerebral artery infarcts. Diffusion or perfusion MRI sequences can be especially helpful in the first few hours after onset of ischemia, when findings on standard T2-weighted MR studies may be absent or subtle.

The posterior circulation Acute Stroke Prognosis Early CT score (pc-ASPECT) has been proposed as a measurement of vertebrobasilar ischemia severity. A pc-ASPECT score of 10 is normal. One point is subtracted for left or right ischemic changes in the thalamus, cerebellar hemisphere, or posterior cerebral artery territory, and 2 points are subtracted if any part of the midbrain or pons is involved (144). A pc-ASPECT score of less than 8 is considered severe. DWI-pc-ASPECTS imaging may provide a more sensitive assessment then CT-based imaging. It has been reported that even with a score of 6 or less, good 90-day clinical outcomes (mRS < 2) were achieved in almost 25% of patients after endovascular reperfusion (92).

MRI can also help distinguish basilar branch infarcts from small artery strokes (61; 177; 19). Basilar branch infarcts tend to produce unilateral ventral pontine infarcts, often larger than 1.5 cm, that extend to the pontine surface. Small artery disease tends to produce small, unilateral tegmental or ventral infarcts that do not reach the surface of the pons. Diffusion weighted MR sequences are helpful in differentiating lesions of recent onset from prior pontine lacunae or leukoaraiosis, as they can appear similar on T2-weighted sequences.

Clues to the status of the basilar artery and related vasculature can be gleaned from standard CT and MR imaging. Calcification of the basilar artery may be seen on CT but does not correlate well with the degree of associated atherosclerosis. Unenhanced CT may show a hyperdense basilar artery before a brainstem infarct is visualized. The presence of a hyperdense basilar artery often is a strong predictor of basilar artery thrombosis if no similar intra-arterial hyperdense changes are seen in the supraclinoid carotid arteries. (71). Absence of normal basilar artery flow voids on MR may indicate occlusion or slow flow, but also may arise from other causes such as in-plane flow effects in a tortuous, but open basilar artery. In addition, a FLAIR-hyperintense basilar artery is a strong marker of occlusion and a predictor of poor outcome (67). Dolichoectasia of the basilar artery may generally be demonstrated on both standard CT and MRI axial images. The MR will show an enlarged vessel often with inhomogeneous intraluminal signal, reflecting in situ thrombus, sometimes compressing the ventral surface of the pons.

Vessel imaging studies are crucial to characterize the status of the basilar artery as, in contrast to the anterior circulation, clinical measures such as the NIH Stroke Scale have been shown to be poor predictors of vascular occlusion in the posterior circulation (82). However, this has significantly improved following high-resolution MRI vessel wall imaging, 5T MRA, and 4D DSA. Other options include magnetic resonance angiography, transcranial Doppler sonography, CT angiography, and catheter angiography. Intracranial magnetic resonance angiography centered on the circle of Willis will demonstrate the basilar artery in its entirety, as well as the distal portions of the feeding vertebral arteries and the initial segments of the exiting posterior cerebral arteries. Magnetic resonance angiography generally correlates well with angiographic findings but has a tendency to overestimate degree of stenosis. However, basilar artery occlusive disease appears to be more accurately characterized on MRA than vertebral occlusive disease (22). CT angiography can rapidly image the basilar, vertebral, and posterior cerebral arteries and is less susceptible to stenosis overestimation (183). Transcranial Doppler can be a useful adjunctive study to confirm magnetic resonance or computerized tomography angiography findings, or to provide some noninvasive test information in patients intolerant of MR or iodinated contrast. The depth and tortuosity of the basilar artery can make insonation difficult, and false-positive and false-negative findings can occur, limiting its utility. Transcranial Doppler is most reliable in characterizing the proximal two thirds of the basilar artery (47; 159). Administration of IV contrast agent during transcranial Doppler sonography enhances insonation of the basilar tip and increases the total length of the basilar artery identified (86; 95; 170).

Although management decisions are often based on noninvasive MRA, CTA, and transcranial Doppler studies alone, functional imaging modalities allow real-time physiologic assessment. These include CT and MR perfusion in which cerebral blood flow, cerebral blood volume, and contrast transit-time are compared to distinguish ischemic versus likely infarcted brain tissue. CT and MR perfusion studies have been well-validated in the anterior circulation. However, their utility in the posterior circulation remains uncertain. The pc-ASPECTS score applied to CT perfusion imaging demonstrated improved performance compared to use of noncontrast CT or CTA source images and may be useful in selecting patients who may benefit from endovascular thrombectomy (182). Catheter cerebral angiography continues to play a crucial diagnostic role in a selective number of patients.

ECG and echocardiography allow screening for sources of cardioembolism. For patients in whom an embolic mechanism is clinically suspected, such as those with top of the basilar syndrome, but in whom no cardioembolic source is confirmed by ECG or transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography with contrast may be considered. Prolonged mobile outpatient cardiac telemetry should be considered in patients with suspected atrial fibrillation, although the duration of such monitoring is a subject of controversy.

• Acute basilar artery stroke is a medical emergency. | |

• Early recognition and diagnosis are crucial for the implementation of time-sensitive treatment. | |

• Acute treatment strategies include intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular thrombectomy. | |

• Management of secondary complications is crucial and may require intensive care unit monitoring. |

General principles of acute stroke treatment fully apply to basilar artery stroke. Acute supportive care includes correction of severe hyperglycemia and hyperthermia, administration of supplemental oxygen as needed to maintain normal oxygen saturation, intubation if the airway is threatened by bulbar weakness or altered sensorium, assessing swallowing function before oral intake is instituted, and administration of isotonic crystalloids to maintain euvolemia (142; 143).

The common occurrence of a slowly progressive or stuttering course suggests that hemodynamic failure may be contributing to basilar artery ischemia. Regulating intravascular volume and blood pressure to improve blood flow may be useful. In general, blood pressure should not be lowered unless it exceeds a systolic pressure of 220 mm Hg or a diastolic pressure of 120 mm Hg; the patient is to be treated by an intravenous thrombolytic agent (< 185/110); or permissive hypertension acutely threatens an existing co-morbidity (eg, heart failure or concomitant myocardial infarction) (142). In select cases with a progressive or fluctuating course, cautious blood pressure augmentation, although not well established, may be beneficial, theoretically taking advantage of collateral pathways. However, the coexistence of active cardiovascular dysfunction (eg, left ventricular failure) may render such patients intolerant of this strategy. Admission to an intensive care unit is often warranted in the setting of profound or unstable neurologic deficits, decreased level of consciousness, hemodynamic instability, or cardiac or respiratory failure.

The natural history of basilar artery occlusion carries such a poor prognosis that acute reperfusion constitutes an important goal for the urgent management of these patients, increasing 2- to 4-fold the odds for a favorable neurologic outcome (110; 97; 74). Studies have demonstrated that failure of basilar artery recanalization is associated with a dismal prospect for favorable outcome (110). Presently, clinical and investigative strategies include intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular rescue techniques (ie, intraarterial thrombolysis, endovascular thrombectomy, and angioplasty with or without stenting combined with best medical management).

Intravenous thrombolytics should be offered to all patients with basilar artery stroke who present within 4.5 hours of onset and who qualify for such treatment based on accepted criteria, even in older children and adolescents (24; 142). However, the reported rates of basilar artery recanalization following intravenous tPA following this approach approximate 40% to 50%, and only 20% to 40% of patients achieve a favorable neurologic outcome (110; 154; 127). Moreover, it is evident that clot burden negatively influences the effectiveness of intravenous thrombolysis. Smaller clots more commonly result in distal basilar artery occlusion and relatively better outcomes (173).

Bridging thrombolytics before endovascular thrombectomy. Multiple randomized trials have demonstrated improved functional outcomes after bridging intravenous thrombolytics prior to endovascular thrombectomy versus direct thrombectomy alone, including the DIRECT-SAFE (126) and SWIFT DIRECT trials (59). Although not FDA approved for use in ischemic stroke, tenecteplase has shown promise for achieving higher rates of recanalization in basilar artery occlusion before endovascular thrombectomy when compared to alteplase (reperfusion > 50%; TNK 26% vs. tPA 7%) based on retrospective observational data (05). EXTEND-IA TNK parts I and II have demonstrated a similar benefit overall; however, the number of basilar artery occlusions in these studies were low (32; 31). Randomized trials are needed to confirm that the recanalization benefit can also be consistently achieved in the basilar artery. The use of intravenous thrombolytics (unless contraindicated in an individual patient) before endovascular thrombectomy is recommended in both the most recent guidelines from the American Stroke Association and European Stroke Organisation (32; 31; 181).

Technological advances have proven the benefit of mechanical thrombectomy in the anterior circulation. There is robust evidence of its utility in the treatment of acute internal carotid artery and middle cerebral artery occlusion, leading to American Heart Association and European Stroke Association guideline recommendations in the treatment of these patients (142).

Only four of 414 patients randomized in the mechanical thrombectomy after intravenous alteplase versus alteplase alone after stroke (THRombectomie des Artères CErebrales [THRACE]) trial and six of 202 patients randomized in the Tenecteplase versus Alteplase before Endovascular Therapy for Ischemic Stroke (EXTEND-IA TNK) trial had basilar artery occlusion (31). Although registry series and retrospective studies have demonstrated the benefit of endovascular thrombectomy in basilar artery occlusion, improving recanalization defined as thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI, score = 2b–3) and favorable neurologic outcome defined as modified Rankin scale of 0 to 2 while reducing 90-day mortality, the first two randomized controlled studies demonstrated neutral outcomes without statistically significant superiority over medical therapy.

The first of two neutral randomized controlled studies, the Basilar Artery Occlusion Endovascular Intervention versus Standard Medical Treatment (BEST) trial, was a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial conducted between 2015 and 2017 (112). It randomized 131 patients with basilar artery occlusion within 8 hours of symptom onset to endovascular thrombectomy plus standard medical therapy (n=66) or standard medical therapy alone (n=65). The primary outcome was a modified Rankin scale score of 3 or lower at 90 days. The trial was terminated early due to poor recruitment and a high crossover rate. In the intention-to-treat analysis, there was no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome (42% in the intervention group vs. 32% in the control group; OR 1.74; 95% CI 0.81 to 3.74), but there was a trend towards favorable outcome in the group utilizing best medical management. The primary safety outcome was 90-day mortality and did not differ between groups. The trial was underpowered due to its early termination.

The second neutral randomized controlled trial, the Basilar Artery International Cooperative Study (BASICS) trial, was a prospective randomized trial of endovascular thrombectomy within 6 hours of symptom onset for stroke due to basilar artery occlusion (101). The trial was conducted between 2011 and 2019 in 23 centers in seven countries and randomized 300 patients to standard medical care or endovascular thrombectomy. Most patients in each group received IV thrombolysis. The primary outcome was a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-3 at 90 days and occurred in 44.2% in the endovascular thrombectomy group and in 37.7% in the medical care group, a difference that was not statistically significant (RR 1.18; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.50). Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage occurred in 4.5% in the endovascular thrombectomy group and in 0.7% in the medical therapy group (RR 6.9; 95% CI 0.9 to 53.0).

There are multiple reasons why these two initial trials failed to demonstrate superiority of endovascular thrombectomy. In both trials, results may have been confounded by the loss of equipoise over the course of the trial period due to positive results from thrombectomy trials in the anterior circulation. This likely led to selection bias, with patients more likely to benefit from endovascular thrombectomy receiving treatment outside of the trial. This resulted in low recruitment and high crossover between groups. For example, of the 424 eligible patients screened in BASICS, 29% (n=124) were not enrolled and were treated outside of the trial; 79% (n=98) of these patients received endovascular thrombectomy. The outcomes in these patients are not known (101). The BEST trial had limited enrollment and a high crossover of patients treated with endovascular thrombectomy (06). The BASICS trial demonstrated slow recruitment, taking 8 years to enroll 300 patients across 23 centers. Initially using an entry criteria NIHSS greater than 10, the slow recruitment rate forced enrollment of less severely affected patients experiencing transient ischemic attack and minor symptoms, which diluted the treatment effect. The substantially high use of intravenous alteplase in BASICS and a greater number of patients randomized to the endovascular thrombectomy group experiencing atrial fibrillation (29%) also reduced the interventional treatment group benefit. Sudden basilar artery occlusion from atrial fibrillation–induced cardiogenic embolization may fare worse after endovascular thrombectomy in comparison to atherosclerotic basilar artery occlusion due to the latter having more time to develop collateral vessels. The BEST trial used first-generation endovascular thrombectomy devices, which were inferior to subsequent devices.

Taken together, these two early studies utilizing endovascular thrombectomy for basilar artery occlusion were inconclusive. However, they demonstrated that arterial recanalization could be successfully achieved by endovascular thrombectomy (75% to 80%) and result in lower mortality (25% to 48%) and better neurologic outcome (ie, mRS 0-2 in approximately 33% to 43%) (97; 73).

Following improvements in patient selection and study design, two randomized control trials in 2022 demonstrated that basilar artery endovascular thrombectomy was superior to best medical management, with good functional outcomes at 90 days with lower mortality.

The Endovascular Treatment for Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion (ATTENTION) trial enrolled patients within 12 hours of estimated time of stroke onset utilizing an NIHSS of greater than 10 and pc-ASPECTS score of less than 6 if younger than 80 years old and less than 8 if older than 80 years old (175). The median pc-ASPECTS score was 9 in the thrombectomy group and 10 in the control group. There was a low crossover rate. Endovascular thrombectomy demonstrated better 90-day functional outcome (mRS 0–3) than the best medical management group, 46% versus 23%, respectively (p < 0.001). Similar to thrombectomy in the anterior circulation, the number needed to treat to achieve an ambulatory outcome was four. The endovascular thrombectomy group was more likely to have a patent basilar artery at 4 hours. Forty percent of the endovascular thrombectomy group experienced basilar artery atherosclerosis requiring angioplasty and stent placement, which prolonged procedure time and increased risk. The symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage rate was 5.3% in the endovascular thrombectomy group versus none in the best medically managed group, counterbalanced against a statistically significant lower mortality in the thrombectomy group (37% vs. 55%, p < 0.001).