Epilepsy & Seizures

Tonic status epilepticus

Jan. 20, 2025

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Worddefinition

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas.

Epilepsia partialis continua is a rare form of simple focal motor status epilepticus of mainly cerebral cortical origin. It manifests with repetitive, regular, or irregular localized clonic muscle twitching, lasting for a few milliseconds and repeated at least every 10 seconds for hours, days, or months without impairment of consciousness. Onset occurs at any age but starts before 16 years of age in a third of cases. Both sexes are equally affected. Prevalence is extremely small, probably less than one per million population.

Causes are multiple and diverse. Rasmussen syndrome and malformations of cortical development are the main causes in children; cerebrovascular disease and brain space-occupying lesions are the main causes in adults. Nonketotic hyperglycemia is the most common reversible cause. The long-term prognosis is cause-dependent and usually poor. Most patients will continue with intractable epilepsia partialis continua and also develop neurologic and cognitive defects. Only a few patients may have remission. Epilepsia partialis continua is typically drug-resistant. When resective surgery is not possible, successful treatment with multiple subpial transections has been reported in a minority of operated patients. In this update, the author details the historical aspects, classification, clinical manifestations, pathophysiology, diagnostic workup, differential diagnosis, and management of epilepsia partialis continua, paying particular attention to recent advances.

|

• Epilepsia partialis continua is a rare type of simple focal motor status epilepticus characterized by continuous, involuntary focal muscle jerking of mainly cortical origin occurring at least every 10 seconds for at least 1 hour and not impairing awareness. | |

|

• Epilepsia partialis continua is a rare condition with a wide range of underlying etiologies; in children, the most common cause is Rasmussen syndrome, and in adults, the most common causes are cerebrovascular disease and neoplasm. | |

|

• Epilepsia partialis continua is typically resistant to medications, and whenever possible, treatment should focus on the underlying cause. | |

|

• The outcome of epilepsia partialis continua is variable and is highly dependent on the underlying cause: seizures are more likely to remit in patients with stroke or other acute insults than in patients with chronic encephalitis. |

In 1894 Aleksei Yakovlevich Kozhevnikov gave a superb description of “corticalis sive partialis continua” by detailing the clinical manifestations of four patients, localized the cause around the motor center, and accurately attributed the disease to chronic encephalitis (41; 42).

See English translation by Asher and Gadjusek and other details in more recent publications (03; 80; 46; 81; 30).

Encephalitis as a definite cause of epilepsia partialis continua was also established in the Western literature by Wilson and Winkelman in 1924 who described three cases with neuropathologic confirmation (85).

Omorokov reviewed 42 cases of “Kozhevnikov syndrome” (as he called it) in the literature and described a further 52 cases from his Siberian clinic (56). Many of his cases with epilepsia partialis continua in Siberia (Kozhevnikov was practicing in Moscow) had acute encephalitis, and a few had cysticercosis. It was much later in 1937 that patients with acute encephalitis and epilepsia partialis continua proved to have Russian spring-summer tick-borne encephalitis (56; 57; 81; 51).

Dereux described over 100 cases of Kozhevnikov syndrome, with many having chronic encephalitis (24). Subsequently, Theodore Rasmussen documented epilepsia partialis continua as a cause of chronic encephalitis in children (63; 62).

In 1966, Juul-Jensen and Denny-Brown published a case series and review of the literature, observing that epilepsia partialis continua could be caused by several pathologic lesions in both cortical and subcortical structures (38). They proposed a definition of the clinical syndrome as “clonic muscle twitching repeated at fairly short intervals in one part of the body for a period of days or weeks.” They suggested that this syndrome differed from most focal epilepsies because in epilepsia partialis continua there is no progression from the tonic to clonic phase and no Jacksonian march from one body area to another.

In 1974, Thomas and colleagues refined the definition of epilepsia partialis continua, based on the review of the clinical characteristics of 32 patients, as a syndrome “characterized by regular or irregular clonic muscular twitches affecting a limited part of the body, occurring for a minimum of 1 hour, and recurring at intervals of no more than 10 seconds” (76).

In 1985, Obeso and colleagues added three additional features to this definition: (1) the muscle jerks should occur spontaneously, (2) action and somesthetic stimuli could provoke jerks in some patients, and, perhaps most significantly, (3) the movements should be of cortical origin (53).

In 1996, Cockerell and colleagues reported 16 patients who underwent detailed clinical and neurophysiological assessments: only six had direct EEG and EMG evidence of a cortical origin of their jerks; five patients had indirect evidence of a cortical origin; two did not have myoclonus of cortical origin but of some other source (brainstem and basal ganglia); and the origin in the remaining three patients was uncertain. The authors simplified the definition of epilepsia partialis continua to “continuous muscle jerks of cortical origin” and suggested the term “myoclonia continua” for situations in which the cause is extracortical (18).

In 2011, a European survey and analysis of 65 cases of the clinical course and variability of non-Rasmussen, nonstroke, motor, and sensory epilepsia partialis continua was published (46).

Other authors have noted that epilepsia partialis continua can be defined in two ways: based on the clinical features alone or by combining clinical with neurophysiologic evidence to confirm the cortical origin of the abnormal movements (09).

ILAE classification, nomenclature, and definition. The ILAE Commission on Classification in 1985 recognized “two types of Kozhevnikov’s syndrome, but only one of these two types is included among the epileptic syndromes of childhood because the other one is not specifically related to this age” (19).

“Kozhevnikov syndrome type 1” referred to epilepsia partialis continua and was defined as follows:

|

This type represents a particular form of rolandic partial epilepsy in both adults and children and is related to a variable lesion of the motor cortex. Its principal features are: (a) motor partial seizures, always well localised; (b) often the late appearance of myoclonus in the same site where somatomotor seizures occur; (c) an EEG with normal background activity and a focal paroxysmal abnormality (spikes and slow waves); (d) occurrence at any age in childhood and adulthood; (e) frequently demonstrable aetiology (tumor, vascular); and (f) no progressive evolution of the syndrome (clinical, electroencephalographic, or psychological). This condition may result from mitochondrial encephalopathy (MELAS). |

“Kozhevnikov type 2 syndrome” was defined as:

|

Childhood disorder, suspected to be of viral etiology, has an onset between 2 and 10 years (peak, 6 years) with seizures that are motor partial seizures but are often associated with other types. Fragmentary motor seizures appear early in the course of the illness and are initially localized but later become erratic and diffuse and persist during sleep. A progressive motor deficit follows, and mental deterioration occurs. The EEG background activity shows asymmetric and slow diffuse delta waves, with ictal and interictal discharges not strictly limited to the Rolandic area. |

In the 1989 ILAE classification, Rasmussen syndrome was introduced as a synonym of Kozhevnikov type 2 syndrome (20). In subsequent ILAE revisions on classification and terminology (26; 25), the name Kozhevnikov was removed (59). The revision of seizure terminology by the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology lists Rasmussen syndrome under the category “distinctive constellations” (08), a name that is now abandoned (21).

Epilepsia partialis continua of Kozhevnikov is a seizure type (26; 25), though this is not mentioned in the ILAE positional papers of the operational classification of seizure types (29; 28).

According to the ILAE epilepsy diagnosis manual, “Epilepsia partialis continua refers to recurrent focal motor seizures (typically affecting hand and face, although other body parts may be affected that occur every few seconds or minutes for extended periods (days or years). The focal motor features may exhibit a Jacksonian march. A Todd’s paresis may be seen in the affected body part” (21).

In the ILAE report on the definition and classification of status epilepticus, epilepsia partialis continua is listed amongst those with prominent focal motor symptoms (77). In the epilepsy classification of the ILAE report, epilepsia partialis continua is listed amongst immune etiology (66).

Epilepsia partialis continua is a prolonged focal motor status epilepticus of segmental muscle twitching lasting a few milliseconds and repeated nearly every second for hours, days, or months. The twitching is limited to a muscle or a small group of contiguous or unrelated muscles on one side of the body. Agonist and antagonist muscles are simultaneously contracted. Facial and hand muscles are preferentially affected. Consciousness is not impaired though some patients in coma may present with the clinical symptomatology of epilepsia partialis continua.

The video shows continuously repetitive lower facial rhythmic and arrhythmic jerks without impairment of consciousness and without discernible ictal EEG changes. Each jerk lasts a few milliseconds and repeated every 1 to 4 seco...

The presentation of the disorder depends on the underlying cause. Patients with localized neoplastic, vascular, or infectious brain lesions may have neurologic deficits and isolated seizures before the onset of the focal status epilepticus (04). However, with metabolic causes, such as nonketotic hyperosmolar hyperglycemia or reactions to certain drugs, the onset of epilepsia partialis continua is sudden (67; 35). On neurologic examination, approximately half of all patients with epilepsia partialis continua may have focal abnormalities, including weakness, sensory loss, or changes in the tendon reflexes (76; 18).

The lengthy focal epileptic muscle twitching of epilepsia partialis continua is characterized by location, frequency, intensity, duration, and coexistence with other types of more conventional seizures (76; 04; 05; 18; 71; 83; 46; 47). Activation reflex, by movement or other means, is characteristic in some patients (53; 67; 17).

Location. Epilepsia partialis continua may involve one muscle or a small muscle group of agonists and antagonists. These may be in the same region (tongue, corner of the mouth, thumb, and other fingers) or occur simultaneously in other locations on the same side without direct anatomical continuity.

Facial and distal muscles of the upper limbs are more commonly affected than proximal or leg musculature. Truncal muscles on one side, such as the rectus abdominus, teres major, or other muscles, may be involved.

Epilepsia partialis continua that involves both sides of the body alternately is exceptional.

Frequency. The frequency and rhythmicity of the muscle jerks vary between patients and even between different limbs and muscle groups within an individual patient. The frequency of the twitches ranges from 0.5 to 10 Hz, although most patients have muscle twitches at a rate of 3 Hz or less (76; 18). Typically, jerks occur about once every second or so. In one quantitative study, 33% of patients experienced 10 jerks/minute, 19% 10 to 20 jerks/minute, and 14% less than 20 jerks/minute (17). Epilepsia partialis continua usually persists during slow-wave sleep, though is often of diminished frequency and intensity. It may be reduced or exaggerated during rapid eye movement sleep (84; 82).

Intensity. The intensity and course of epilepsia partialis continua is variable. Commonly, the jerks are not violent, and the patient, though distressed, can tolerate them well.

The video shows continuously repetitive lower facial rhythmic and arrhythmic jerks without impairment of consciousness and without discernible ictal EEG changes. Each jerk lasts a few milliseconds and repeated every 1 to 4 seco...

Intensity varies from nearly inconspicuous to visible repetitive rapid movements of the affected parts.

In many patients, the twitching starts suddenly and reaches peak intensity almost immediately after onset, either gradually improving or remaining unchanged over time. In other patients, the twitching is mild at onset and gradually increases in intensity as time progresses (76).

Duration. The duration of the twitching is variable, ranging from a few hours to years, although most patients display twitching for less than 1 month (76; 71). Each jerk lasts for only a few milliseconds.

Activation. Epilepsia partialis continua is “aggravated by action or sensory stimuli” in approximately one-third of patients (76; 53; 71; 46). Movement or other means of activation of the affected muscles may be a characteristic feature in some patients (67; 46). In other patients, loud noises, anxiety, and certain postures can aggravate or improve the twitching (76; 46).

Other seizure types. About 60% of patients exhibit, in addition to epilepsia partialis continua, other types of seizures, such as motor focal seizures or secondarily tonic-clonic seizures and, more rarely, complex focal seizures. These may occur independently, or they may precede or follow the appearance of epilepsia partialis continua. More often, motor focal seizures are interspersed with epilepsia partialis continua.

The long-term prognosis of epilepsia partialis continua depends on the underlying cause. Epilepsia partialis continua secondary to transient metabolic disturbances or medication effects may resolve with correction of the underlying abnormality or removal of the offending agent. In epilepsia partialis continua associated with Russian spring-summer encephalitis, the focal clonic movements are usually unresponsive to medical therapy, and surgical excision seems to offer the only hope of remission (87). Epilepsia partialis continua secondary to Rasmussen syndrome is also usually associated with a poor outcome. There is a progressive phase in most patients, with a mean duration of 5.3 years in a series, followed by static neurologic dysfunction (54). In a few exceptional patients, the epilepsia partialis continua disappeared after some months to years, suggesting that the disease can "burn out." Epilepsia partialis continua associated with a structural lesion is often poorly responsive to medication and either resolves spontaneously over time or responds to surgical excision. The outcome is probably better in patients with epilepsia partialis continua secondary to ischemic stroke (76; 71). There may be a weakness in muscle groups involved in the clonic activity, which can persist after the epilepsia partialis continua abates. It is unclear to what extent this may be due to persistent epileptic discharges or the underlying lesion.

In a retrospective series of 26 patients with epilepsia partialis continua of various causes, 11 patients were alive, and 15 had died during a follow-up period of 1 to 18 years (76). Additional series demonstrated lower rates of mortality of 4% to 6% (18; 71). In a series of 76 patients with epilepsia partialis continua, 60% of patients were controlled on medications, whereas 36% of patients were not controlled and 4% of patients died as a result of the underlying cause of epilepsia partialis continua. The underlying cause largely determines the outcome; seizures were more likely to remit in patients with stroke or other acute insults than in patients with encephalitis (76; 71).

In a European survey and analysis of 65 cases with non-Rasmussen, nonstroke, motor, and sensory epilepsia partialis continua, three types with two subtypes each were described (46):

(1) Epilepsia partialis continua as a solitary event (de novo or in preexistent epilepsy). This group consisted of 12 cases of different etiology and pathogenesis, both de novo (n = 7), and in established epilepsy (n = 5). The episodes lasted from 4 days to 3 months, except for one patient with probable herpes simplex encephalitis who died after 36 hours.

(2) Chronic repetitive non-progressive epilepsia partialis continua (with frequent or rare episodes). This group included a total of 18 cases having this pattern for up to 29 years. This type seems not to be homogeneous but to split into two subgroups. In the first (2a, “frequent,” n = 10), the single episodes of epilepsia partialis continua lasted not longer than 24 hours and occurred more than once per month. In the other subgroup (2b, “rare,” n = 8), the single episodes lasted several days up to some weeks and occurred at longer intervals of typically several months. Within one episode of type 2b, epilepsia partialis continua could be fully continuous or present with brief interruptions. Both patterns remained stable over periods up to 29 (2a) and 25 years (2b), respectively.

(3) Chronic persistent nonprogressive epilepsia partialis continua (primarily or evolving out of an episodic course). This group had a total of 35 cases, lasting from 1 to 25 years. In seven of these, epilepsia partialis continua started with episodes (3 type 2a and 4 type 2b) and after 3 months to 4 years secondarily evolved into the persistent type. The reverse course was seen only once--not as a spontaneous evolution but as a partial effect to therapy with tiapride.

In a series of 51 children, the outcome assessed at the end of a long follow-up period showed unchanged neurologic status in 10 children, neurologic consequences in 33 children, and lethal outcome in eight children (43).

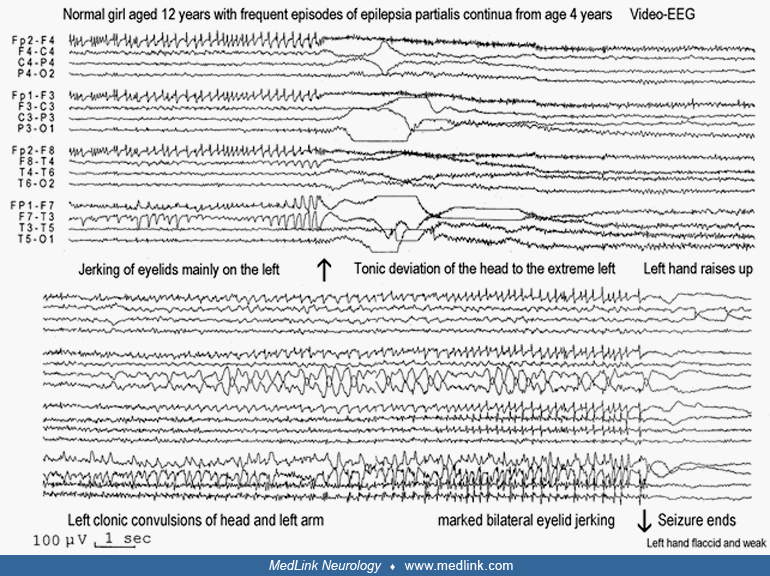

Clinical vignette 1: Epilepsia partialis continua of unknown cause. A 12-year-old girl had epilepsia partialis continua, which started at the age of 4 years and continued to date of examination with increasing frequency and duration. Fast (3 to 10 Hz) twitching of the left eyelid occurred simultaneously with the left rectus abdominis (during the examination she pointed close to the midline by the umbilicus) and a muscle in the armpit (probably the latissimus dorsi). This lasted from hours to 2 to 3 days and was continuous day and night. This was interspersed with ipsilateral left-sided, focal motor seizures mainly affecting the face and upper limbs. Additionally, there was postictal, and probably ictal, left hemiparesis mainly of the upper limb. She did not lose consciousness during these attacks and communicated well. She was also able to understand, but could not speak, during the focal motor seizures. She had never had a tonic-clonic seizure.

Initially, the seizures occurred once or twice per year but eventually progressed to the point they were occurring every 2 weeks. Neurologic and mental status was normal. High-resolution brain MRI was normal. All appropriate tests for metabolic or other diseases associated with epilepsia partialis continua were normal. Drug treatments had failed; only rectal diazepam provided temporary relief during the attacks.

Differential diagnosis. Epilepsia partialis continua is a focal motor status epilepticus that may occur in different conditions and has several etiologies (59). In a child, the first syndrome that comes to mind is Kozhevnikov-Rasmussen syndrome. However, the patient’s good clinical status over the years, as well as her normal MRI and the lack of background EEG abnormalities, was rather against this diagnosis, though some exceptional cases of Kozhevnikov-Rasmussen syndrome in which deterioration occurs 10 years after onset of epilepsia partialis continua have been described.

Clinical vignette 2: Epilepsia partialis continua due to focal cortical dysplasia, treated surgically. A 22-year-old woman with epilepsy since childhood was admitted to the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit for evaluation. Her first seizure was a generalized tonic-clonic seizure at 7 years of age. After this, she began having complex partial seizures characterized by left-arm extension, drooling from the left side of her face, and behavioral arrest. At peak severity, she had up to five complex partial seizures per day. Many antiepileptic medications were attempted without success before the patient became seizure-free for several months on topiramate, approximately 1 year before the admission.

Six months earlier, she had experienced continuous rhythmic twitching of her left eyelid, cheek, lips, tongue, and chin. She also had tightness in her throat, hoarseness, and difficulty swallowing. She had been evaluated at other institutions and had been treated with phenobarbital, topiramate, oxcarbazepine, and levetiracetam, with no benefit. Her general and neurologic examinations were normal, except for dysarthria, hoarseness, and jerking movements of the left side of her mouth and face at a rate of approximately 0.5 Hz.

Her EEG showed continuous focal slowing in the right hemisphere, which was maximal in the right frontocentral region, intermittently rhythmic, and sharply contoured.

Brain MRI showed a focal region of increased T2 signal in the cortex and subcortical white matter of the posterior right inferior frontal gyrus.

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) showed a region of decreased metabolism in the right temporal and inferior frontal lobes.

Because of ongoing epilepsia partialis continua, the patient underwent surgical resection of the lesion in the right inferior frontal gyrus.

She underwent awake craniotomy with electrocorticography to determine the margins of the epileptiform activity and to preserve language, motor, and sensory function. Her seizures stopped immediately after the resection, and her only neurologic dysfunction postoperatively was mild, left-sided tongue weakness that did not affect her speech. Pathologic examination of the resected brain tissue revealed focal cortical dysplasia.

Approximately 6 months after surgery, she began experiencing simple partial seizures characterized by an unusual cephalic sensation, followed by clonic jerking of the left side of her face and mouth. Some of the seizures would progress to impairment in awareness. These occurred as clusters of one to three seizures every few months.

Due to ongoing refractory seizures, she underwent additional epilepsy surgery at 26 years of age, 4 years after the prior surgery. She underwent intracranial monitoring with subdural grids and strips over portions of the right frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes. The interictal and ictal recordings demonstrated multiple independent epileptogenic foci in the right perisylvian area. There were also continuous, rhythmic epileptiform discharges in the right precentral gyrus, corresponding to subtle, continuous clonic jerking of the left side of the patient’s tongue.

A second resection was performed, including the (nondominant) primary tongue motor region, which demonstrated only gliosis on pathological examination. Postoperatively, the only neurologic deficit was a mild exacerbation of her tongue weakness, not affecting speech. At her last follow-up appointment, 6 months after surgery, she had no further complex partial seizures and rare, brief focal clonic seizures affecting her left face, in the context of missed medications.

Most authors agree (or require by definition) that epilepsia partialis continua is cortically generated, and involvement of the primary motor cortex is necessary to generate the muscle twitches. In the past, Juul-Jensen and Denny-Brown suggested that epilepsia partialis continua could be generated subcortically, based on the electrophysiological and pathologic features of nine patients with acute cerebral lesions with subcortical damage (38). This paper created a controversy regarding cortical versus subcortical origin and the differentiation from myoclonus. However, the patients in this report had large cerebral lesions, and cortical structures were also affected in most cases. Cockerell and colleagues suggested referring to extracortical continuous muscle jerking as “myoclonia continua” (18).

In almost all cases, the generator of the muscle jerks is in the primary motor cortex contralateral to the jerking muscles. However, Young and Blume reported epilepsia partialis continua of the right upper limb associated with periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges in the right parasagittal region (86). This was in a patient with a history of a large right hemisphere infarction as a result of complications of a right posterior communicating aneurysm clipping. The authors postulated that the jerks arose from direct projections from the right supplementary motor area to the medullary reticular formation.

In Kozhevnikov-Rasmussen syndrome, the disease process is more widespread, with diffuse patchy inflammatory changes in the cortex and white matter (microglial nodules, perivascular cuffs of small lymphocytes and monocytes, multifocal neuronal loss, and some spongy degeneration) depending on the features of the disease activity (64). See the MedLink Neurology article, Rasmussen syndrome, for further details.

The list of diseases related to epilepsia partialis continua is wide, reflecting the diverse etiology of the disease.

The cause of epilepsia partialis continua is abnormal electrical activity in the brain brought on by different causes:

|

• Inflammatory (chronic or acute encephalitis) | |

|

• Architectural brain disease | |

|

• Metabolic disease | |

|

• Mitochondrial disorders (eg, FARS2 mutations) | |

|

• Lesional diseases of the brain (eg, ischemic, neoplastic) | |

|

• Adverse effect of drugs | |

|

• Genetic causes |

A discussion of the pathophysiology of epilepsia partialis continua is problematic because of the lack of a widely accepted definition of the syndrome. In the past, the absence of epileptiform EEG abnormalities in some patients with epilepsia partialis continua (60) and the presence of epilepsia partialis continua in patients with subcortical lesions but preserved cortex (38; 11) led to the hypothesis that epilepsia partialis continua had a subcortical origin in some patients.

Three studies using depth electrode recordings provided the most definitive neurophysiologic evidence for a cortical origin of epilepsia partialis continua (06; 13; 84). Wieser and colleagues used quantitative methods to establish a definite temporal relationship between the muscle jerks and rhythmic electrical discharges in the motor cortex in a 14-year-old girl with a 5-year history of intermittent epilepsia partialis continua.

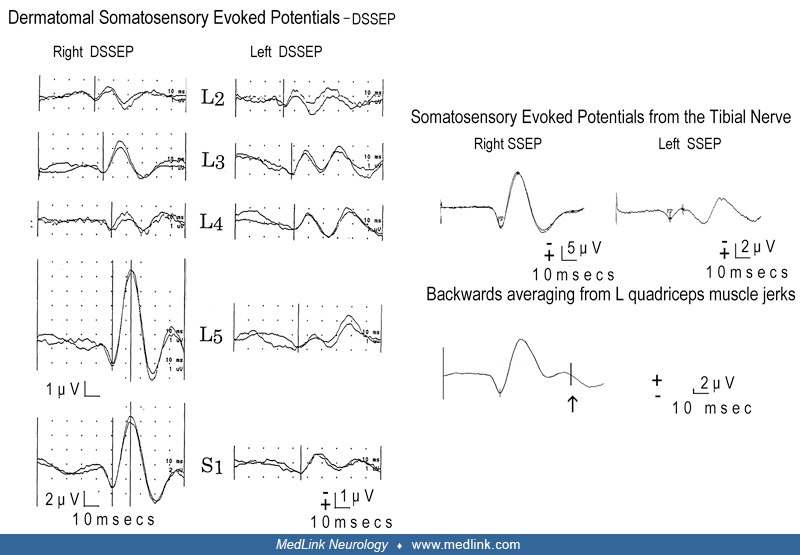

Less invasive methods can be used to distinguish muscle jerks of cortical origin from those of subcortical and brainstem or spinal origin. Shibasaki and Kuroiwa used a technique of back-averaging where the EEG signal was time-locked to the EMG signal of the jerking muscle to demonstrate an epileptiform EEG abnormality consistently preceding muscle jerks in four of seven patients with continuous focal myoclonus (68). These abnormalities were in the central region contralateral to the muscle jerking, suggesting that the origin of the clonus was in the contralateral motor cortex. Further evidence that the jerks originated from the abnormal function of the motor cortex came from the fact that somatosensory-evoked potentials in patients with presumed cortical myoclonus were abnormally enlarged (69). Obeso and colleagues reported the neurophysiologic features of 11 patients with different types of cortical myoclonus, including spontaneous and stimulus-sensitive myoclonus, epilepsia partialis continua, Jacksonian seizures, and generalized seizures (53). The EEG, back-averaged EEG, and somatosensory-evoked potentials characteristics in these patients were remarkably similar, regardless of the clinical manifestations. This suggests that epilepsia partialis continua is simply repetitive cortical myoclonus.

An experimental model of epilepsia partialis continua provided further evidence of origin in the motor cortex. In this model, Chauvel and Lamarche injected aluminum hydroxide into the motor cortex of monkeys, producing focal clonic muscle jerks (16). This model was useful in proving the role of long-loop reflexes in the generation of cortical myoclonus. Thermocoagulation of the thalamic nucleus ventroposterolateral oralis disrupted the reflex loop and led to a cessation of the myoclonus in most cases (37). The participation of the ventrolateral and intralaminar thalamic nuclei in the epileptic process was illustrated on FDG-PET by a simultaneous metabolic increase in both the cortex and the ipsilateral thalamus in a patient with epilepsia partialis continua (33).

In one study, three patients showed suppression of postsynaptic high-frequency somatosensory evoked potential burst and an amplitude reduction of the P24 wave of the low-frequency somatosensory evoked potentials. These components, which are related to cortical inhibitory interneuron activity, were normal in two patients with rolandic lesions but without epilepsia partialis continua (36). The authors concluded that these results support the hypothesis that epilepsia partialis continua might be correlated to dysfunction of GABA-ergic interneurons of a cortical sensory-motor network (36).

Subcortical or spinal myoclonus should be considered in a patient with continuous focal muscle jerking where neurophysiologic evidence of cortical origin is not available. As discussed in the introduction, many authors believe that the diagnosis of epilepsia partialis continua should refer exclusively to cortical myoclonus. Cockerell and colleagues suggested referring to extracortical continuous muscle jerking as “myoclonia continua” (18). Menini and Naquet called this variant type C myoclonus and suggested that the origin of the myoclonus might be in the brainstem (49). This variety is not as common or as well studied as the cortical myoclonus, and it is not clear whether this syndrome should be classified as an epileptic disorder or a movement disorder. See the MedLink Neurology article on myoclonic status epilepticus for further information on myoclonus and myoclonic status epilepticus.

Because most publications about epilepsia partialis continua are case reports and small series of patients, no good epidemiological data exist. Based on their survey of all registered cases in the United Kingdom in 1993, Cockerell and colleagues estimated the prevalence of epilepsia partialis continua to be less than one per million population (18).

Epilepsia partialis continua should not be difficult to diagnose on clinical grounds. There are not many other conditions that exhibit the characteristic segmental, continuous muscle twitching of this type. However, its diagnosis can sometimes be challenging, especially if movements are confined to a very small body region or strongly resemble movements encountered in other conditions, including "painful legs and moving toes syndrome" (12). Furthermore, EEG may or may not be useful. A normal ictal EEG is not against this diagnosis. Brain imaging may or may not be abnormal.

A main difficulty is to differentiate the genuine cortical from the noncortical cases, and this is often a formidable task without appropriate neurophysiological examinations (jerk-locked back averaging, somatosensory evoked responses, and sequential EMG). In clinical terms, the coexistence of other types of focal epileptic seizures practically identifies cortical epilepsia partialis continua. The differential diagnosis includes other syndromes that cause continuous focal body movements. It is usually possible to distinguish epilepsia partialis continua from the following movements.

Nonepileptic myoclonus. Jerks are nearly continuous, erratic, and often movement induced. In most myoclonus syndromes, the jerks are diffuse or multifocal. Continuous focal or segmental myoclonus (myoclonia continua) can be differentiated from epilepsia partialis continua because the neuroimaging and/or neurophysiologic features suggest subcortical or spinal origin.

Tremor. Tremor can particularly be differentiated from epilepsia partialis continua when the contraction affects agonist and antagonist muscles alternatively.

Parkinson disease. Parkinson disease often presents with unilateral or focal rhythmic limb movements and can be distinguished from epilepsia partialis continua because of the presence of associated features, including rigidity, akinesia, and postural instability.

Other movement disorders. These include dystonia, choreoathetosis, tics, and psychogenic movements. These can usually be distinguished on examination or based on associated clinical features, but there are reports of movement disorders coexisting with epilepsia partialis continua.

Nonepileptic facial nerve hemifacial spasm and facial tics may sometimes cause problems in the differential diagnosis. This peripheral type of hemifacial spasm is defined as unilateral, involuntary, irregular clonic or tonic movement of muscles innervated by the seventh cranial nerve. It manifests with unilateral, painless, irregular, and continuous clonic twitching of the facial muscles. It affects mainly women, aged 50 to 60 years, without known antecedent causes other than Bell palsy in a few cases. The spasms usually begin in the orbicularis oculi and gradually spread to other facial muscles and the platysma of the face. Most frequently attributed to vascular loop compression at the root exit zone of the facial nerve, the spasm-related electromyogram activity is probably generated by ephaptic transmission due to local demyelination at the entry zone of the facial nerve root. However, many other etiologies of unilateral facial movements must be considered in the differential diagnosis. In all such cases, EEG is normal during hemifacial spasms. Spread and variable synkinesis on blink reflex testing and high-frequency discharges on EMG with appropriate clinical findings are diagnostic. Stimulation of one branch of the facial nerve may spread and elicit a response in a muscle supplied by a different branch. Synkinesis is not present in essential blepharospasm, dystonia, or seizures. Needle EMG shows irregular, brief, high-frequency bursts (150 to 400 Hz) of motor unit potentials, which correlate with clinically observed facial movements.

Patient report. A 50-year-old woman had nearly continuous twitching in the left side of the face for 2 months. The diagnosis of hemifacial spasms was made by eminent neurologists. However, MRI and subsequent surgery revealed a large glioblastoma in the right side of the brain (58).

Limb-shaking transient ischemic attacks associated with severe stenosis of the internal carotid artery may also imitate focal clonic seizures (61). Limb-shaking is precipitated by rising or exercise (the arm is more frequently involved than the leg), usually lasts less than 5 minutes, and is often accompanied by paresis of the involved limb.

Epilepsia partialis continua is a rare condition with a wide range of underlying etiologies. It may be associated with focal, multifocal, or diffuse brain pathology and may include numerous syndromes (Tables 1 and 2) (76; 54; 18; 71; 70; 07; 45).

|

(76) |

(18) |

(71) |

(74) |

Total (percent) n=198 | |

|

Age range of patients (in years) |

0.5 to 76 |

1 to 84 |

1 to 81 |

0,1/13 | |

|

Cerebrovascular disease |

9 |

9 |

18 |

0 |

36 |

|

Rasmussen syndrome |

-- |

7 |

7 |

30 |

44 |

|

Neoplastic disease |

5 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

13 |

|

Meningoencephalitis |

5 |

-- |

8 |

0 |

13 |

|

Other CNS infection |

-- |

1 |

10 |

0 |

11 |

|

Hyperglycemia |

-- |

1 |

6 |

7 | |

|

Perinatal injury |

-- |

2 |

4 |

1 |

7 |

|

Inherited metabolic disease |

2 |

4 |

1 |

12 | |

|

Other acquired metabolic disorders |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 | |

|

Trauma |

9 |

7 |

17 |

0 | |

|

Other |

11 |

|

Chronic or acute encephalitis |

• Kozhevnikov-Rasmussen syndrome |

|

Metabolic disorders |

• Non-ketotic hyperglycemic diabetes mellitus, particularly when associated with hyponatremia |

|

Lesional brain diseases |

• Cerebrovascular disease, brain tumor, abscess, trauma, metastasis, granuloma, cysticercosis, hemorrhage, infarct, arteriovenous malformation and cortical vein thrombosis, neurosarcoidosis |

|

Drugs |

• Penicillin and azlocillin-cefotaxime (and the old contrast media metrizamide) may induce epilepsia partialis continua |

|

Others |

• Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease, COVID-19/SARS2 infection (79), mitochondrial disorders |

|

Unknown (20%) | |

|

| |

Epilepsia partialis continua is most likely a manifestation of focal dysfunction within the motor cortex, so every patient with epilepsia partialis continua should have a general medical and neurologic evaluation to determine potential causes of this dysfunction. This evaluation should include brain MRI to identify a lesion in or around the motor cortex. In children, when neuroimaging and general medical evaluation are nondiagnostic, testing for specific metabolic and hereditary disorders may be appropriate.

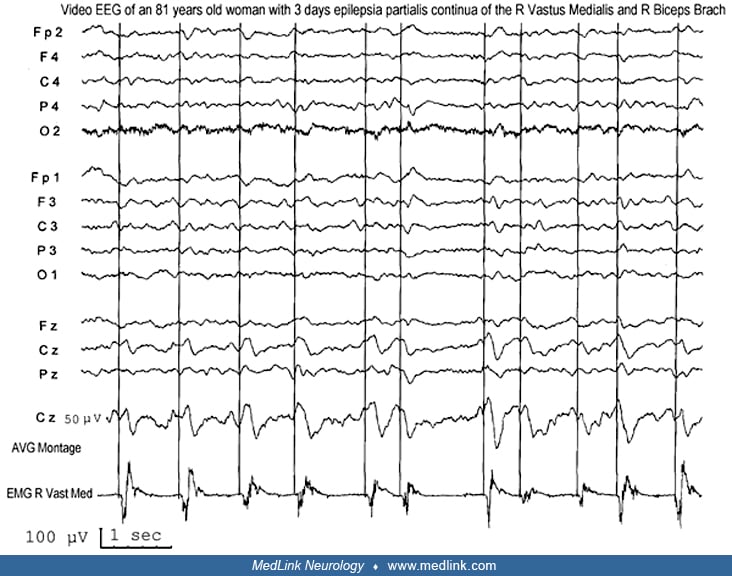

Neurophysiologic tests may be useful in distinguishing epilepsia partialis continua from myoclonic limb movements or other movement disorders that are not of cortical origin. EEG may show focal spikes or rhythmic focal slowing in the central region contralateral to the jerking limb. However, in many cases, standard scalp EEG recording will show no abnormalities, most likely because a relatively large area (about 10 cm2) of synchronously depolarizing cortex is required to produce an ictal EEG correlate on scalp EEG (75). Jerk-locked back-averaged EEG, which averages the EEG time-locked to the EMG signal in the jerking limb, is a more sensitive technique for detecting evidence of the cortical origin of the clonic limb movements.

Using this technique, one can demonstrate focal slow waves or epileptiform discharges in the contralateral peri-rolandic region (68). Jerk-locked, back-averaged magnetoencephalography (MEG) has also been used to identify potential dipole sources in a few patients with epilepsia partialis continua (55) Additionally, somatosensory evoked potentials in the affected limb may produce abnormally enlarged cortical potentials on the contralateral scalp (69), providing further evidence of hyperexcitability of the contralateral rolandic cortex. In patients with epilepsia partialis continua and no definite abnormality on standard neuroimaging, additional modern neuroimaging may help identify the origin of the myoclonus.

In patients with suspected Rasmussen syndrome, documentation of progressive hemispheric atrophy on neuroimaging is important in supporting the diagnosis.

Other pathologic findings on MRI, MR spectroscopy, SPECT, and PET may help provide early diagnostic clues and in guiding the location for a confirmatory brain biopsy. EEG usually demonstrates frequent or continuous lateralized epileptiform discharges and regional slowing in one hemisphere that gradually worsens as the disease progresses. CSF may be abnormal with an elevation of protein and lymphocytes, but a normal CSF does not rule out the diagnosis of Rasmussen syndrome.

The clinical, video-EEG, and neuroimaging findings from two cases of epilepsia partialis continua with video presentation have been reported (27).

An important contribution to diagnostics is the discovery of new antibodies by genetic and immunological laboratory investigations. In the case of epilepsia partialis continua of unknown origin in which an inflammatory etiology is suspected, it is important to research plasma and CSF as well as autoantibodies such as anti-MOG because several case reports have been reported.

Treatment should concentrate on the underlying cause, especially with reversal of iatrogenic or metabolic disturbances. In epilepsia partialis continua secondary to an autoimmune process, such as a paraneoplastic syndrome, anti-GAD antibodies, or anti-MOG antibodies, treatment of the underlying disorder with immune-modulating therapy, such as corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, or intravenous gammaglobulin, may result in cessation of muscle jerks.

There is also steroid-responsive epilepsia partialis continua with anti-thyroid antibodies. Hashimoto encephalopathy is thought to cause various clinical presentations including seizures, myoclonus, and epilepsia partialis continua. A 33-year-old Japanese woman acutely developed epilepsia partialis continua in the right hand as an isolated manifestation. Thyroid ultrasound showed an enlarged hypoechogenic gland, and a thyroid status assessment showed euthyroid with high titers of thyroid antibodies. A brain MRI revealed a nodular lesion in the left precentral gyrus. Corticosteroid treatment resulted in a cessation of the symptom (48).

Epilepsia partialis continua can sometimes be managed with antiseizure medications, though there are no controlled trials. Small series have reported effective treatment with phenytoin, primidone, carbamazepine, clonazepam, valproic acid, levetiracetam, topiramate, lacosamide, and perampanel either as monotherapy or in combination (67; 18; 71; 46; 72; 73; 02; 01; 50).

There are reports of effective treatment of Rasmussen syndrome with antiviral agents as well as corticosteroids, intravenous gammaglobulin, plasmapheresis, and other immune-modulating therapies. A complete discussion of the medical treatment options in Rasmussen syndrome is beyond the scope of this article. See a detailed update by Cay-Martinez and colleagues and the MedLink Neurology article, Rasmussen syndrome, for further information (14).

Botulinum toxin injection may be useful in the amelioration of continuous focal muscle jerks in epilepsia partialis continua (39).

In persistent epilepsia partialis continua secondary to a structural lesion, surgical resection may be necessary. However, the epileptogenic lesion often involves the primary motor cortex, and resection would result in disabling motor dysfunction. Extraoperative cortical mapping with subdural grids, strips and depth electrodes, or intraoperative mapping may allow for a more tailored resection with preservation of primary motor and sensory function (44). However, in some instances, epilepsia partialis continua due to focal cortical dysplasia may shift sides and reemerge in the contralateral, previously asymptomatic, hemibody (34). A mechanism of disinhibition by surgery of a suppressed contralateral and homologous epileptogenic zone is speculated. Three patients who underwent resection of the motor cortex under acute electrocorticography had reemergence of medically intractable epilepsia partialis continua in the other side of the body after rolandic resection. Two patients died, and the third continued with refractory attacks (34). A published case report presented the results of multimodality evaluation of a 15-year-old young man with longstanding focal motor epilepsy affecting his right leg, which had become refractory to treatment (40). High-resolution 3T MRI revealed a subtle focal cortical dysplasia at the bottom of a sulcus near the medial aspect of the left precentral gyrus. After confirmation of the extent of the lesion with PET and ultra-high-field 7T MRI, the patient underwent cortical mapping and focal resection and has remained free of seizures. When surgery is not possible, multiple subpial transections may be a treatment option.

In epilepsia partialis continua secondary to Rasmussen syndrome or other disorders causing severe multifocal hemispheric dysfunction, anatomical or functional hemispherectomy may be the most effective treatment for seizure control (10; 32), although the decision to pursue surgery must be weighed against the risk of postoperative functional impairment.

Robotic thermocoagulative hemispherotomy seems to be a safe, feasible, and bloodless procedure with a very low morbidity rate and promising outcomes (15). Repetitive low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a relatively benign treatment, and there is preliminary evidence that it may be effective in controlling epilepsia partialis continua in some patients. In a report of two children with epilepsia partialis continua of unknown etiology, rTMS produced focal cerebral hypoperfusion (as demonstrated on HMPAO SPECT) in the region that was stimulated (31). In one patient, the muscle jerks stopped within 24 hours of stimulation, whereas the other patient experienced no clinical improvement. In a series of seven patients with epilepsia partialis continua secondary to various causes, three patients experienced transient (20 to 30 min) cessation of limb movements, whereas two patients experienced longer-lasting improvement (65). Only one patient was still seizure-free over a 4-month follow-up period. The side effects were transient head and limb pain as well as limb stiffening, but all of these resolved with cessation of stimulation.

Application of transcranial direct current stimulation (iDCS) daily has been useful as an adjunctive therapy in a patient with epilepsia partialis continua (caused by mitochondrial disease) who failed to respond to five antiepileptic drugs at maximal doses (52). The electrical and clinical seizures stopped after 3 days of tDCS. The second course of tDCS was administered for 14 days when the focal seizures re-emerged a month later. The patient tolerated the procedure well. Following 4 months of hospitalization and prolonged community rehabilitation, the patient was able to return to full-time education with support, and there is no report of cognitive deficit (52).

Daoud and colleagues reported three patients undergoing a long-term protocol of multichannel tDCS (22). The patients received several cycles (11, 9, and 3) of 5 consecutive days of stimulation at 2 mA for 2 × 20 min, targeting the epileptogenic zone (EZ), including the central motor cortex with cathodal electrodes. The primary measurement was seizure frequency changes. tDCS cycles were administered over 6 to 22 months. The outcomes comprised a reduction of at least 75% in seizure frequency for two patients, and in one case, a complete cessation of severe motor seizures. However, tDCS had no substantial impact on the continuous myoclonus characterizing epilepsia partialis continua. No serious side effects were reported. Vagus nerve stimulation has been reported as an effective option for epilepsia partialis continua when medical treatment fails and other more invasive neurosurgical options are not feasible (23). Four children with medically unresponsive epilepsia partialis continua secondary to chronic inflammatory encephalopathy (two cases), Rasmussen encephalitis (one case), and poliodystrophy (one case) underwent vagus nerve stimulation treatment. After a mean follow-up of 3 years, one child stopped epilepsia partialis continua, two presented short and rare episodes, and in one patient two to three residual seizures per day were reported. In all cases, the reduction of epileptic activity was associated with mild improvement of motor and cognitive abilities. No serious side effects were reported (23).

Valentin and colleagues presented two patients with focal, drug-resistant epilepsia partialis continua, who were admitted for intracranial video-EEG monitoring to elucidate the location of the epileptogenic focus and identification of eloquent motor cortex with functional mapping (78). In both cases, the focus resided at or near the eloquent motor cortex and, therefore, precluded resective surgery. Chronic cortical stimulation delivered through subdural strips at the seizure focus (continuous stimulation at 60 to 130 Hz, 2 to 3 mA) resulted in a greater than 90% reduction in seizures and abolition of the epilepsia partialis continua after a follow-up of 22 months in both patients. Following permanent implantation of cortical stimulators, no adverse effects were noted. Epilepsia partialis continua restarted when intensity was reduced or batteries depleted. Battery replacement restored the previous improvement.

Evidence of enhanced neuroinflammation in the genesis of epilepsia partialis continua has led to an increased interest in potential therapeutic targets. In particular, the emerging role of cytokines and chemokines in the pathogenesis of other epilepsy syndromes has been extensively studied as a target for precision therapy. Neuroinflammation is a very common cause of epilepsia partialis continua in children. New targeted therapy against neuroinflammation could quickly become an effective treatment.

All contributors' financial relationships have been reviewed and mitigated to ensure that this and every other article is free from commercial bias.

Pasquale Striano MD PhD

Dr. Striano of the University of Genova, Istituto Gaslini, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

See ProfileAlessandro Orsini MD PhD

Dr. Orsini of Santa Chiara Children’s Hospital in Pisa, Italy has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

See Profile

Solomon L Moshé MD

Dr. Moshé of Albert Einstein College of Medicine has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

See ProfileNearly 3,000 illustrations, including video clips of neurologic disorders.

Every article is reviewed by our esteemed Editorial Board for accuracy and currency.

Full spectrum of neurology in 1,200 comprehensive articles.

Listen to MedLink on the go with Audio versions of each article.

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Epilepsy & Seizures

Jan. 20, 2025

Epilepsy & Seizures

Jan. 09, 2025

Epilepsy & Seizures

Jan. 09, 2025

Epilepsy & Seizures

Dec. 23, 2024

Epilepsy & Seizures

Dec. 19, 2024

Epilepsy & Seizures

Dec. 03, 2024

Epilepsy & Seizures

Dec. 03, 2024

Epilepsy & Seizures

Dec. 02, 2024