Peripheral Neuropathies

Gold neurotoxicity

Dec. 30, 2024

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Worddefinition

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas.

Hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning is the most common neurotoxic presentation of mushroom toxicity. Two main toxidromes associated with hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning are related to the responsible toxin: the psilocybin toxidrome and the muscimol/ibotenic acid toxidrome. Hallucinogenic mushroom toxins produce their associated toxidromes by selectively affecting neurotransmission. Psilocybin and psilocin have serotonergic properties, whereas muscimol is a potent, selective agonist for the GABAA receptors and binds to the same site on the GABAA receptor complex as GABA itself.

Magic mushrooms continue to be fashionable among drug users, especially young drug users, in part because they are often believed to be relatively harmless compared to other hallucinogenic drugs. However, serious adverse outcomes have been reported, including myocardial infarction; severe rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, and posterior encephalopathy; and protracted paranoid psychosis. Ingestion of magic mushrooms may result in horror trips combined with self-destructive and suicidal behavior, especially among people with mental or psychiatric disorders (34; 22). Serious and often permanent organ dysfunction or fatalities may result from accidentally ingesting a more toxic mushroom resembling one that is hallucinogenic (eg, mushrooms of the genus Cortinarius, which are nephrotoxic).

No particular diagnostic procedures are available or needed for most patients with hallucinogenic mushroom toxicity. Care of patients with hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning is primarily supportive and symptomatic. Most patients with hallucinogenic mushroom toxicity can be treated without medications. Seizures are uncommon with hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning, except in young children. The vast majority of poisoned individuals recover without serious permanent morbidity. However, uncommon fatalities and serious adverse outcomes do occur and include suicide, protracted psychosis, and myocardial infarction.

|

• Management of hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning is primarily supportive and symptomatic. | |

|

• Hallucinogenic mushroom toxins produce their associated toxidromes by affecting neurotransmission. | |

|

• Hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning is rarely fatal. | |

|

• Other serious and often permanent organ dysfunction or fatalities may result from accidentally ingesting a more toxic mushroom resembling one that is hallucinogenic. |

Basidiomycota are filamentous fungi composed of hyphae and reproduce sexually. Basidiomycota include inter alia some fungi that might be grown or foraged for food (eg, mushrooms, puffballs, bracket fungi, other polypores, and chanterelles) and fungi that infest plants and might be secondarily ingested (eg, smuts, bunts, rusts). The toxidromes associated with fungi of the phylum Basidiomycota include forms of hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning. With hallucinogenic mushrooms ("magic mushrooms" or "shrooms"), exposure to the fungal toxins is generally intentional, whereas the exposure is generally accidental with other forms of mushroom poisoning.

Hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning. Hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning is the commonest neurotoxic presentation of mushroom toxicity.

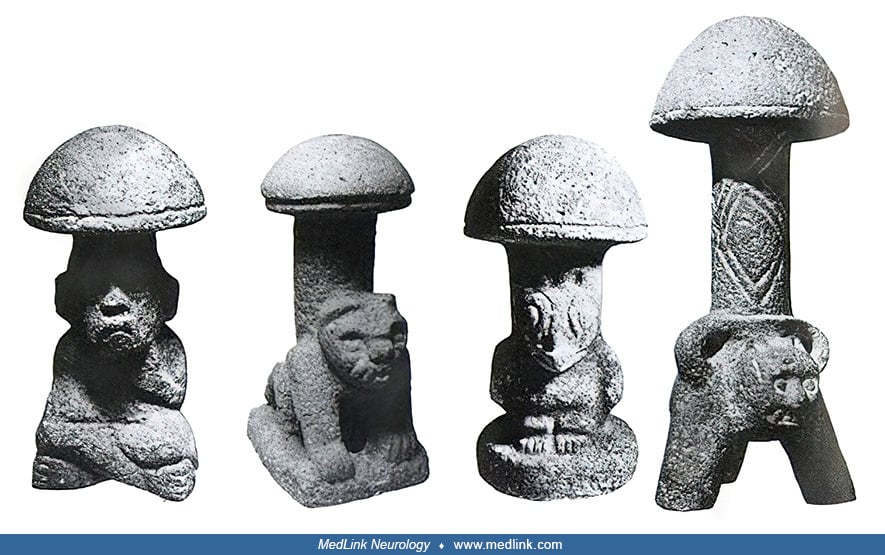

Psilocybin-containing mushrooms have been used in indigenous New World cultures in religious, divinatory, or spiritual contexts for millennia (35; 42). They are represented in the Pre-Columbian sculptures and glyphs seen throughout North, Central, and South America.

In 1800, Everard Brande first reported hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning in the Western medical literature: the disorder affected a father and four of his children, in varying degrees, as a function of age and quantity ingested (dose-response effect) (06). The portion of the report dealing with one child is abstracted below:

|

J.S. gathered early in the morning of the third of October [1799], in the Green Park [in London], what he supposed to be small mushrooms; these he stewed with the common additions in a tinned iron saucepan. The whole did not exceed a tea saucerful, which he and four of his children ate the first thing, about eight o'clock in the morning, as they frequently had done without any bad consequence; they afterwards took their usual breakfast of tea, & c. which was finished about nine, when Edward, one of the children (eight years old), who had eaten a large proportion of the mushrooms, as they thought them, was attacked with fits of immoderate laughter, nor could the threats of his father or mother restrain him. To this succeeded vertigo, and a great degree of stupor, from which he was roused by being called or shaken, but immediately relapsed. The pupils of his eyes were, at times, dilated to nearly the circumference of the cornea, and scarcely contracted at the approach of a strong light; his breathing was quick, his pulse very variable, at times imperceptible, at others too frequent and small to be counted; latterly, very languid; his feet were cold, livid, and contracted; he sometimes pressed his hands on different parts of his abdomen, as if in pain, but when roused and interrogated as to it, he answered indifferently, yes, or no, as he did to every other question, evidently without any relation to what was asked. ... By four o'clock every violent symptom had left him, drowsiness and occasional giddiness only remaining, both of which, with some head-ach, continued during the following day. |

These mushrooms were later identified as Psilocybe semilanceata ("liberty cap"). Its popular name is based on its resemblance to a Phrygian cap or liberty cap, which is emblematic of a slave's manumission (release from slavery) in classical antiquity. Such a cap is incorporated into the seal of the United States Senate and is portrayed in many iconic images of the national personification symbols of Liberty for the United States and of Marianne for the French Republic since the French Revolution, with similar representations in many other countries. In the 1960s, this species was found to contain the hallucinogenic compound psilocybin.

Lewis Carroll. English author, poet, and mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832–1898) is better known by his pen name: Lewis Carroll. His most notable works are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass (1871).

Photographic self-portrait, taken June 2, 1857, around the time that Carroll drafted the stories that made him famous. This photograph was first published in Carroll's biography by his nephew, Stuart Dodgson Collingwood. (Sourc...

In the late 1850s, Dodgson became friends with the family of the new Dean of Christ Church, Henry George Liddell (1811–1898). Dodgson grew into the habit of taking the Liddell children on rowing trips accompanied by an adult friend. On one such excursion in 1862, Dodgson developed the outline of a story that he told to one of the children, Alice Liddell, and she begged him to write it down. Dodgson eventually presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled Alice's Adventures Under Ground in November 1864 as "A Christmas gift to a Dear Child in Memory of a Summer Day." The original illustrations were by Dodgson, and even though these do not compare to the later iconic images of Sir John Tenniel (1820–1914), they do give a sense of what Carroll had in mind for what were later interpreted to be hallucinogenic experiences. Of most relevance here was Alice's meeting with the hookah-smoking blue caterpillar on top of a mushroom.

This occurred after Alice ate a bite of cake that had been labeled "Eat me." From Alice's Adventures Under Ground (1864). Manuscript by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. (Public domain. Image edited by Dr. Douglas J Lanska.)

|

Alice looked all round her at the flowers and the blades of grass, but could not see anything that looked like the right thing to eat under the circumstances. There was a large mushroom near her... She stretched herself up on tiptoe, and peeped over the edge of the mushroom and her eyes immediately met those of a large blue caterpillar, which was sitting with its arms folded, quietly smoking a long hookah, and taking not the least notice of her or of anything else (Carroll 1864). |

Later, the caterpillar and Alice discussed what size she wanted to be:

|

[I]n a few minutes the caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth, and got down off the mushroom, and crawled away into the grass, merely remarking as it went: "the top will make you grow taller, and the stalk will make you grow shorter." "The top of what? the stalk of what [?"] thought Alice. "Of the mushroom," said the caterpillar, just as if she had asked it aloud, and in another moment it was out of sight. Alice remained looking thoughtfully at the mushroom for a minute, and then picked it and carefully broke it in two, taking the stalk in one hand, and the top in the other. "Which does the stalk do?" she said and nibbled a little bit of it to try: the next moment she felt a violent blow on her shin: it had struck her foot! She was a good deal frightened by this very sudden change, but as she did not shrink any further, and had not dropped the top of the mushroom, she did not give up hope yet. There was hardly room to open her mouth, with her chin pressing against her foot, but she did it at last, and managed to bite off a little bit of the top of the mushroom. "Come! my head's free at last!" said Alice in a tone of delight, which changed into alarm in another moment, when she found that her shoulders were nowhere to be seen: she looked down upon an immense length of neck, which seemed to rise like a stalk out of a sea of green leaves that lay far below her. |

Dodgson's manuscript was ultimately published as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in 1865 under the Lewis Carroll pen name. In Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, as in the earlier manuscript, Alice tried portions of the stalk and cap of a mushroom and subsequently experienced distortions of her body image (08; 10). This phenomenon of self-experienced paroxysmal body image illusions involving distortions of the size, mass, or shape of the body or its position in space, often occurring with depersonalization and derealization, was later incorporated into English psychiatrist John Todd’s description of Alice in Wonderland syndrome in 1955 (44; 28; 27). Although there is no evidence that Dodgson ever tried hallucinogenic mushrooms, he did take belladonna alkaloids--plant-derived anticholinergic agents that have "deliriant" and hallucinogenic potential—for his insomnia and migraine (23). Apparently, he was also aware of accounts of the hallucinogenic effects of Siberian fly agaric mushrooms (23).

English illustrator Sir John Tenniel’s (1820-1914) illustration of Alice meeting the hookah-smoking caterpillar seated on a mushroom, from Lewis Carroll’s “The Nursery ‘Alice’” (Carroll 1889). Alice’s experiences were used as t...

The seeming references to hallucinogenic mushroom ingestion in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) were revisited a century later. For example, "White Rabbit" is an Alice in Wonderland-inspired song written by Grace Slick, reportedly after a drug-induced "trip" (ie, during a temporary altered state of consciousness induced by consumption of a hallucinogenic substance, most commonly LSD, mescaline, or psilocybin mushrooms). The song specifically references hallucinatory experiences after ingesting "some kind of mushroom" and refers to the similar experiences of "Alice," the protagonist of Lewis Carroll's fantasy works (08; 09; 10):

|

When men on the chessboard |

|

• Two main toxidromes associated with hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning are related to the responsible toxin: the psilocybin toxidrome and the muscimol/ibotenic acid toxidrome. | |

|

• At low doses, psilocybin produces perceptual distortions and alterations of thought or mood, with preserved awareness and minimal effects on memory and orientation. | |

|

• Ingestion of muscimol/ibotenic acid–containing mushrooms often produces a syndrome with gastrointestinal upset, CNS depression, and CNS excitation, either alone or in combination. | |

|

• Seizures may occur in children who ingest muscimol/ibotenic acid–containing mushrooms. |

Two main toxidromes associated with hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning are related to the responsible toxin: the psilocybin toxidrome and the muscimol/ibotenic acid toxidrome.

Hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning (psilocybin toxidrome). Among the classifications of mushroom poisoning, this toxidrome corresponds to Group C of Barbato (01), Group 6 of Blackman (04), Group 2A of White (45), and Group 6 of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (20).

At low doses, psilocybin produces perceptual distortions and alterations of thought or mood, with preserved awareness and minimal effects on memory and orientation. Alterations in perception and euphoria typically begin within 30 minutes of ingesting the psilocybin-containing mushrooms, though such manifestations may not develop for up to 2 hours. Symptoms generally last between 4 and 12 hours, depending on the amount ingested.

Various CNS manifestations have been reported, including euphoria, irritability, fear, agitation, depressed level of consciousness (ranging from lethargy to coma), confusion or delirium, incoherent babbling, misperceptions, hallucinations, delusions, dizziness, ataxia, myoclonus, seizures (mostly in young children), etc. Among the reported visual "hallucinations" is the perceived motion of stationary objects or surfaces, although this is, in fact, a perceptual disturbance of something that is actually seen and, hence, strictly speaking, a visual illusion rather than a hallucination. Other manifestations may include nausea, sympathomimetic activity (eg, mydriasis and tachycardia), hypotension, and hyperpyrexia (in children).

In addition, a clinical trial of psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depression found that individuals in at least one of the higher-dose psilocybin arms had more frequent headache, nausea, and anxiety at initiation of therapy (19). Subsequently, the higher-dose psilocybin arms had increased suicidal ideations and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors.

Hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning (muscimol/ibotenic acid toxidrome). Among classifications of mushroom poisoning, this toxidrome corresponds to Group D of Barbato (01), Group 5 of Blackman (04), Group 2C of White (45), and Group 3 of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (20).

Several mushroom species (eg, Amanita muscaria, A pantherina, and apparently A aprica) contain ibotenic acid and muscimol and may cause both excitatory and sedating symptoms. Ingestion of muscimol/ibotenic acid–containing mushrooms often produces a syndrome with gastrointestinal upset, CNS depression, and CNS excitation, either alone or in combination. In a study of ingestions of ibotenic acid and muscimol-containing mushrooms reported to a U.S. regional poison center from 2002 to 2016 (32), 34 cases met the inclusion criteria: 23 cases of ingestion of Amanita muscaria, 10 of A pantherina, and one of A aprica. Reasons for ingestion included foraging (12), accidental (eg, in young children) (12), recreational (6), therapeutic (1), self-harm (1), and unknown (2). Twenty-five patients (74%) were symptomatic, and all but one developed symptoms within 6 hours. Six patients had symptoms for less than 6 hours, whereas 15 had symptoms lasting less than 24 hours. Ingestion of A pantherina was more likely to cause symptoms than ingestion of A muscaria in terms of gastrointestinal symptoms (80% vs. 35%), CNS depression (70% vs. 35%), and CNS excitation (70% vs. 35%). Five patients (ie, 20% of the symptomatic cases) were intubated. No deaths were reported.

Five frayed panther cap (A pantherina) fruiting bodies were eaten by mistake by two persons (27 and 47 years of age), resulting from a confusion of toxic mushrooms with edible species (39). Symptom onset occurred after 120 min, with CNS depression, variable obtundation, hallucinations, religious delusions, ataxia, and hyperkinetic behavior.

In another report, dried fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) fruiting bodies were eaten by five young persons (aged 18 to 21 years) at a party, producing the intended visual and auditory hallucinations in four of them, but instead producing unconsciousness resulting in hospitalization in the fifth person (38).

One study reported the clinical features and management of nine cases of mushroom poisoning in infants and children due to Amanita pantherina (eight cases) and Amanita muscaria (one case) who were admitted to a children's hospital (02). Most ingestions were in toddlers, with boys more frequently involved. Symptom onset was between 30 and 180 minutes after ingestion, with the onset of CNS depression, variable obtundation, intermittent agitation, hallucinations, ataxia, or hyperkinetic behavior. Vomiting was rare. Seizures or myoclonic twitching occurred in four patients (44%) but was controlled with standard anticonvulsant therapy. Recovery was rapid and complete in all patients.

Magic mushrooms continue to be fashionable among drug users, especially young drug users, in part because they are often believed to be relatively harmless compared to other hallucinogenic drugs (03). However, serious adverse outcomes have been reported, including myocardial infarction (05); psilocybin-induced takotsubo cardiomyopathy (26); severe rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, and posterior encephalopathy (03); psychosis and mania complicated by violent behavior and rhabdomyolysis (43); and protracted paranoid psychosis (07). Ingestion of magic mushrooms may result in horror trips combined with self-destructive and suicidal behavior, especially among people with mental or psychiatric disorders (34; 22).

Despite the potential for serious adverse outcomes, magic mushroom ingestion is relatively safe (25). Out of 9233 magic mushroom users, 19 (0.2%) reported having sought emergency medical treatment in the past year, with a per-event risk estimate of 0.06%. Young age was the only predictor associated with a higher risk of emergency medical presentations. The most common symptoms were psychological: anxiety/panic and paranoia/suspiciousness. All but one returned to baseline within 24 hours.

Although fatal A pantherina poisoning has been reported in the Pacific Northwest (39), human deaths related to muscimol/ibotenic acid–containing mushrooms are rare and mainly occur in young children, the elderly, or those with serious chronic illnesses.

The duration of clinical manifestations after Amanita muscaria (fly agaric or fly amanita) ingestion does not usually exceed 24 hours; however, paranoid psychosis with visual and auditory hallucinations can appear 18 hours after ingestion and can last for up to 5 days (07). A 48-year-old man with no previous medical history gathered and ate mushrooms he presumed to be A caesarea but which were instead A muscaria. Half an hour later he started to vomit. He was subsequently found unresponsive, having a seizure-like episode. He was comatose on admission 4 hours after ingestion. Laboratory results, including blood and urine toxicology analysis, and a brain CT scan were normal, except for an elevated creatine kinase level. Activated charcoal was administered. Ten hours after ingestion, he awoke and was fully orientated, but he became confused and uncooperative 8 hours later (18 hours after ingestion). Paranoid psychosis with visual and auditory hallucinations subsequently appeared and persisted until these manifestations gradually resolved on the sixth day. Follow-up 1 year later found no symptoms of psychiatric disease.

Serious and often permanent organ dysfunction or fatalities may result from accidentally ingesting a more toxic mushroom resembling one that is hallucinogenic. For example, some individuals who intend to harvest or procure "magic mushrooms" (ie, hallucinogenic mushrooms) obtain species that are more toxic instead, like some species of mushrooms of the genus Cortinarius, which are nephrotoxic (36).

A common feature among all species in the genus Cortinarius is that young specimens have a "cortina" (veil) between the cap and the stem, hence the name, which means “curtained.” The renal toxicity of these mushrooms can vary, presumably based on toxin dose and physical constitution, from mild, transient renal failure to irreversible total acute renal failure that necessitates continual dialysis (36). The nephrotoxicity of Cortinarius orellanus was first recognized in the 1950s, when this mushroom was identified as the cause of a mass poisoning of 135 people in Bydgoszcz, Poland, that resulted in 19 deaths (16). Affected individuals develop an acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (with severe interstitial nephritis, acute focal tubular damage, and interstitial fibrosis). The responsible toxin was identified to be orellanine, a bipyridine N-oxide compound. The onset of renal symptoms is typically delayed for 1 to 2 weeks after ingestion, although patients may have gastrointestinal discomfort in the latency period (16).

|

• Mushrooms with significant psychoactive hallucinogenic effects fall into two main groups: (1) mushrooms containing psilocybin; and (2) mushrooms containing ibotenic acid and muscimol (isoxazoles). | |

|

• Both ibotenic acid and muscimol can cross the blood-brain barrier. | |

|

• Hallucinogenic mushroom toxins produce their associated toxidromes by selectively affecting neurotransmission. | |

|

• Psilocybin and psilocin are structurally similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine). | |

|

• Muscimol is a potent, selective agonist for the GABAA receptors and binds to the same site on the GABAA receptor complex as GABA itself. This is in contrast to other GABAergic drugs, such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines, which bind to separate regulatory sites. |

Mushrooms with significant psychoactive hallucinogenic effects fall into two main groups: (1) mushrooms containing psilocybin; and (2) mushrooms containing ibotenic acid and muscimol (isoxazoles). Both ibotenic acid and muscimol can cross the blood-brain barrier.

Hallucinogenic mushroom toxins produce their associated toxidromes by selectively affecting neurotransmission.

|

• Psilocybin and psilocin are both indolealkylamines that can be considered as derivatives of tryptamine. They are structurally similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) (46). | |

|

• Muscimol is a potent, selective agonist for the GABAA receptors and activates the receptor for the brain's principal inhibitory neurotransmitter, displaying sedative-hypnotic, depressant, and hallucinogenic activity (24). Muscimol binds to the same site on the GABAA receptor complex as GABA itself. This is in contrast to other GABAergic drugs, such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines, which bind to separate regulatory sites. | |

|

• Ibotenic acid, or (S)-2-amino-2-(3-hydroxyisoxazol-5-yl)-acetic acid, is a psychoactive toxin that occurs naturally in Amanita muscaria and related species of mushrooms that are found in the temperate and boreal regions of the Northern Hemisphere. It is a conformationally restricted analogue of the neurotransmitter glutamate and acts as a particularly potent agonist of the NMDA receptor and multiple types of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Ibotenic acid also serves as a prodrug to muscimol. |

Psilocybin-containing mushrooms. Psilocybin mushrooms, commonly known as "magic mushrooms" or "shrooms," are a polyphyletic (ie, derived from more than one common evolutionary ancestor or ancestral group) group of fungi that contain the hallucinogenic neurotoxin, psilocybin. In fact, more than 50 species of fungi contain psilocybin (and its derivative psilocin); most of these are small brown or tan mushrooms. Biological genera containing psilocybin mushrooms include Psilocybe, as well as Gymnopilus, Inocybe, Panaeolus, Pholiotina, and Pluteus.

Hallucinogenic mushrooms resemble the common store mushroom Agaricus bisporus, although the flesh of Psilocybe mushrooms characteristically turns blue or green when bruised or cut. Because it is difficult to distinguish non-psilocybin species from the hallucinogenic ones by morphological observation in the wild, psilocybin-containing mushrooms may also be easily ingested unintentionally. Conversely, those seeking hallucinogenic species may inadvertently ingest those with greater toxicity.

Psilocybin-containing hallucinogenic mushrooms are frequently used as drugs of abuse, particularly in adolescents and young adults, and are available fresh, treated/preserved (eg, dried, cooked, frozen), or as dry powders or capsules (41; 05; 37; 38; 33).

Psilocybin toxicology. Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) is a prodrug that is converted into the pharmacologically active form, psilocin, by dephosphorylation after ingestion. Psilocin itself is also present in the mushrooms in small amounts. Psilocybin and psilocin are both indolealkylamines that can be considered as derivatives of tryptamine and are structurally similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) (46). Besides psilocybin and psilocin, two further tryptamines (baeocystin and norbaeocystin) are present in these mushrooms as minor components.

Muscimol/ibotenic acid–containing mushrooms. The fly agaric mushroom (Amanita muscaria) occurs in coniferous and deciduous woodlands of the Northern Hemisphere.

It has often been the model for mushrooms in artistic representations of fairies, gnomes, and elves. Amanita muscaria has been consumed in Asia as a hallucinogen for centuries and possibly millennia: its use in this capacity in the Kamchatka Peninsula and Siberia was recognized in the West by the mid-19th century (13). It may be confused with several edible species (Lycoperdon spp, Calvatia spp, Amanita caesarea) (31). The mushroom’s species name comes from the Latin word musca, for fly, because the mushroom was often used to attract and catch flies (hence, also its common name, “fly agaric”). Other mushrooms with these toxins are A pantherina (also called “panther” or “panther amanita”) and apparently A aprica as well.

Other Amanita species may contain muscimol and ibotenic acid in addition to muscarine (11). Inosperma species may variously contain muscimol and ibotenic acid as well as muscarine (29).

Muscimol/ibotenic acid toxicology. The name of the toxin muscarine derives from the Amanita muscaria mushroom from which it was first isolated by German chemists Oswald Schmiedeberg (1838-1921) and Richard Koppe at the University of Dorpat, who reported their findings in 1869 (40). However, although present, the concentration of muscarine in this mushroom is actually quite low, and the neurotoxicity of this particular mushroom is instead related to muscimol and ibotenic acid (31).

Muscimol, also known as agarin or pantherine, is chemically an isoxazole (ie, a type of azole or 5-membered heterocyclic compound containing a nitrogen atom and at least one other noncarbon atom, and specifically for an isoxazole, an azole with an oxygen atom next to the nitrogen).

Pharmacologically, muscimol is a potent, selective agonist for the GABAA receptors, activating the receptor for the brain's principal inhibitory neurotransmitter and displaying sedative-hypnotic, depressant, and hallucinogenic activity (24). Muscimol binds to the same site on the GABAA receptor complex as GABA itself, which is in contrast to other GABAergic drugs, such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines, which bind to separate regulatory sites.

The effects of muscimol begin 30 to 120 minutes after consumption and last for 5 to 10 hours. These include euphoria; dream-like states; out-of-body experiences; nausea and stomach discomfort; increased salivation; muscle twitching or tremors; and, in large doses, strong dissociation or delirium. About one third of the muscimol ingested is excreted unchanged, and the rest is conjugated or oxidized (31).

Ibotenic acid, or (S)-2-amino-2-(3-hydroxyisoxazol-5-yl)-acetic acid, is a psychoactive toxin that occurs naturally in Amanita muscaria and related species of mushrooms that are found in the temperate and boreal regions of the Northern Hemisphere. It is a conformationally restricted analogue of the neurotransmitter glutamate and acts as a particularly potent agonist of the NMDA receptor and multiple types of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Ibotenic acid also serves as a prodrug to muscimol when the mushroom is ingested, converting to muscimol in vivo via decarboxylation; apparently it acquires its psychoactive properties in this way. However, in humans, most of the ibotenic acid ingested is excreted unchanged in the urine, with only some of it being metabolized to muscimol (31).

|

• Intentional intoxication with hallucinogenic mushrooms continues to be a significant problem in the United States and in parts of Europe. | |

|

• In the United States, the vast majority of mushroom poisoning cases reported to a poison control center with potentially neurotoxic exposures were for hallucinogenic mushrooms. | |

|

• The largest category of identified mushroom exposures reported to poison control centers in the United States was represented by psilocybin/psilocin-containing hallucinogenic mushrooms. | |

|

• Fatal outcomes from hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning are rare. |

Intentional intoxication with hallucinogenic mushrooms continues to be a significant problem in the United States and in parts of Europe. Among 174 adolescents already identified as substance abusers, a quarter (26%) reported having used hallucinogenic mushrooms, frequently in conjunction with alcohol or other drugs, typically producing intoxication for 5 to 6 hours (41). Among undergraduate college students, psilocybin users were significantly more likely than nonusers of psilocybin to use other drugs (eg, cocaine, ecstasy, opiates, nonprescribed prescription drugs, and LSD) (21).

From data collected between September 2008 and December 2009, the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 8% of high school students had used a hallucinogenic drug (eg, LSD, phencyclidine [PCP; "angel dust"], mescaline, or hallucinogenic mushrooms) at least once in their life (17). Hallucinogen use was more common among males (10.2%) than among females (5.5%) and more common among Caucasians (9.0%) than among Hispanics (7.9%) or African Americans (3.3%).

Although seizures of hallucinogenic mushrooms are not consistently monitored in Europe, 19 countries reported 950 seizures of hallucinogenic mushrooms in 2019, amounting to 55 kilograms (18). Among young adults (aged 15 to 34), the most recent national surveys report prevalence estimates for hallucinogenic mushroom use equal to or less than 1%, except for Finland (2.0% in 2018), Estonia (1.6% in 2018), and the Netherlands (1.1% in 2019).

In the 2019 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System, there were 5799 reports of single-substance exposures to mushrooms; the type of mushroom was unknown or unidentified in 76% (20). Categories of potentially neurotoxic exposures with substantial numbers of individuals affected were (using their classification system): 33 cases of Group 2 (muscimol/ibotenic acid); 49 cases of Group 3 (monomethylhydrazine); 18 cases of Group 4 (muscarine/histamine); 10 cases of Group 5 (coprine); and 590 cases of Group 6 (psilocybin/psilocin). Thus, the vast majority with potentially neurotoxic exposures were for hallucinogenic mushrooms (Groups 2 and 6).

The largest category of identified mushroom exposures reported to poison control centers in the United States was represented by psilocybin/psilocin-containing hallucinogenic mushrooms (20). Of 590 case mentions, there were 387 single exposures, meaning that many of these exposures involved multiple individuals simultaneously. Of the 387 exposures, 144 involved individuals aged 13 to 19, 188 involved individuals aged 20 years and older, and 55 involved adults of unknown age; 331 (96%) of these 346 exposures in adolescents and adults were acknowledged to have been intentional.

In 2019, there were no fatalities in these categories of potentially neurotoxic mushroom exposures reported to poison control centers in the United States (20). However, 354 individuals were treated in a healthcare facility, and of these, 112 (32%) suffered a minor adverse outcome, 176 (50%) suffered a moderate adverse outcome, and eight (2%) suffered a major adverse outcome.

Occasional fatalities following Amanita muscaria ingestion have been reported (30).

|

• Prevention is optimally achieved by eating only non-hallucinogenic mushrooms that are commercially cultivated for human consumption. | |

|

• If used, illicit recreational hallucinogenic mushrooms should be kept out of reach from children. | |

|

• Mushroom foragers should eat only one type of wild mushroom and save a sample in a dry paper bag for later identification, if this proves necessary. |

Prevention is optimally achieved by eating only non-hallucinogenic mushrooms that are commercially cultivated for human consumption. If used, illicit recreational hallucinogenic mushrooms should be kept out of reach from children. Mushroom foragers should eat only one type of wild mushroom and save a sample in a dry paper bag for later identification, if this proves necessary.

If ingestion or poisoning is suspected, various toxins need to be considered (depending on the particular presenting symptoms), including alcohol, cannabis, other hallucinogens (LSD, PCP, etc.), glue sniffing, nitrous oxide, anticholinergics, opiates, sympathomimetics (eg, methamphetamine, cocaine), etc. When considering hallucinogenic mushroom toxicity, it is important to keep in mind that (1) recreational exposures are often multiple; (2) mushrooms obtained by foraging are frequently misidentified; and (3) mushrooms obtained illicitly may also be misidentified and may contain adulterants.

|

• No particular diagnostic procedures are available or needed for most patients with hallucinogenic mushroom toxicity. | |

|

• The diagnosis of hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning should be based on the presenting syndrome and supported, if possible, by the description and toxicological analysis of the mushroom. | |

|

• Unfortunately, the exact mushroom species and toxins in cases of hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning typically go unidentified. | |

|

• Ideally, a sample of the mushrooms ingested should be obtained so identification can be confirmed by a mycologist. | |

|

• The regional poison control center may be contacted for consultation, referral, and assistance in mushroom identification. | |

|

• In the United States, a nationwide telephone number automatically directs calls to the nearest poison control center (1-800-222-1222). |

The diagnosis of mushroom poisoning should be based on the presenting syndrome, and supported, if possible, by the description and toxicological analysis of the mushroom (14; 15). Unfortunately, according to data from the American Association of Poison Control Centers, the exact mushroom species in cases of hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning often go unidentified (14; 15; 20). Ideally, a sample of the mushrooms ingested should be obtained so identification can be confirmed by a mycologist. In most cases, the mushroom in question has already been digested, but collecting the patient’s gastric contents by means of gastric lavage or after emesis might yield identifiable spores.

No particular diagnostic procedures are available or needed for most patients with hallucinogenic mushroom toxicity, although identification of the mushroom by a mycologist is still desirable. The regional poison control center may be contacted for consultation, referral, and assistance in mushroom identification. In the United States, a nationwide telephone number automatically directs calls to the nearest poison control center (1-800-222-1222). A mycologist can also be contacted through the North American Mycological Association, a local university, or sometimes a botanical garden.

The following blood studies are recommended for most patients with possible mushroom toxicity evaluated on an emergency basis: complete blood count, basic serum metabolic profile, baseline liver and renal function studies, and creatine kinase. Urine drug testing should also be considered, especially if the patient exhibits alterations of behavior or mental status, or if substance abuse, suicidal intent, or foul play is suspected.

|

• For hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning, care is primarily supportive and symptomatic. | |

|

• Most patients with hallucinogenic mushroom toxicity can be treated without medications. | |

|

• Seizures are uncommon with hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning, except in young children. |

Gastrointestinal decontamination. There is a very limited and somewhat controversial role for gastrointestinal decontamination in cases of mushroom poisoning, with some advocating the use of activated charcoal in the first hour and others discounting this as lacking evidence of efficacy. Furthermore, the CNS manifestations of hallucinogenic mushroom toxicity develop rapidly after ingestion, with absorption before activated charcoal is usually considered. A reasonable approach is to consider activated charcoal administration in patients who are alert and who present for care within 1 hour of hallucinogenic mushroom ingestion. Patients admitted to the hospital are typically given activated charcoal to stop the absorption of toxic compounds and to prevent further intoxication, even though adsorption to activated charcoal has not been demonstrated for these fungal toxins. Supportive evidence for the efficacy of activated charcoal administration in this setting is largely indirect, from animal studies and from analogy with other toxic ingestions. Because of the potential for further volume depletion, the combination of a cathartic (eg, sorbitol) and activated charcoal is not generally recommended.

Syrup of ipecac administration in remote locations soon after pediatric ingestion of toxic mushrooms may prevent or minimize toxicity, but unsupervised children typically only try exploratory nibbles of mushrooms in their local environments and, thus, rarely have serious consequences. Because most serious mushroom poisonings are only detected hours after ingestion, gastric emptying by gastric lavage or syrup of ipecac in the emergency department is not likely to be beneficial. If treatment occurs within the first hour of ingestion, gastric lavage may be considered; however, this recommendation also lacks strong empiric evidence. Nasogastric aspiration in alert patients to obtain a sample for spore analysis can be considered if no other mushroom sample of what was ingested is available and gastric contents might still contain partially digested mushrooms.

Hallucinogenic mushroom toxicity. In hallucinogenic mushroom toxicity, the most frequent form of neurotoxic mushroom poisoning, care is primarily supportive. Most patients can be treated without medications. Toxicity usually lasts between 6 and 8 hours, but some symptoms may take several days to subside.

CNS excitation with agitation and "panic attacks" may occur with hallucinations after ingestion of psilocybin-containing mushrooms. Patients with these findings should initially be placed in a quiet room. With severe agitation, benzodiazepines (eg, midazolam or lorazepam) may prove helpful.

Seizures are uncommon with hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning, except in young children. Seizures may occur in children, particularly after ingestion of mushrooms that contain muscimol and ibotenic acid. Initial management includes oxygenation, support of the airway and breathing, and administration of anticonvulsants (eg, lorazepam). Various anticonvulsants have been used to treat seizures in such patients, but respiratory depression may occur when some of these agents (eg, benzodiazepines) are administered intravenously.

Special attention should be given to monitoring breathing, airway control, and circulation. Intravenous fluids may be necessary to correct volume loss from vomiting. In rare cases, anticholinergic drugs, such as atropine, may be needed. With A muscaria poisoning, anticholinergic drugs (eg, atropine) are rarely, if ever, needed; the species name was applied because muscarine was first identified from preparations of this mushroom, even though few muscarinic effects are observed following ingestion of these mushrooms.

In the absence of a clinically evident infection, it is unnecessary to treat low-grade fever with antipyretics in an agitated or hyperactive patient with hallucinogenic mushroom ingestion.

If symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain begin 5 to 6 hours or more after ingestion, mushrooms that can cause potentially life-threatening or severe toxicity (eg, A phalloides or Cortinarius spp) should be considered.

The vast majority of poisoned individuals recover without serious permanent morbidity. Neurologic presentations of hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning are rarely fatal. Factors that increase the risk of a fatal outcome include age (eg, young children or the elderly) and amount ingested. Uncommon fatalities and serious adverse outcomes do occur, however, and include suicide, protracted psychosis, and myocardial infarction.

All contributors' financial relationships have been reviewed and mitigated to ensure that this and every other article is free from commercial bias.

Douglas J Lanska MD MS MSPH

Dr. Lanska of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and the Medical College of Wisconsin has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

See ProfileNearly 3,000 illustrations, including video clips of neurologic disorders.

Every article is reviewed by our esteemed Editorial Board for accuracy and currency.

Full spectrum of neurology in 1,200 comprehensive articles.

Listen to MedLink on the go with Audio versions of each article.

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Peripheral Neuropathies

Dec. 30, 2024

General Child Neurology

Dec. 11, 2024

General Neurology

Dec. 02, 2024

General Neurology

Nov. 09, 2024

General Neurology

Nov. 05, 2024

Headache & Pain

Nov. 04, 2024

Peripheral Neuropathies

Oct. 25, 2024

Peripheral Neuropathies

Jul. 17, 2024