Sleep Disorders

Sleeptalking

Jan. 18, 2025

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Worddefinition

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas.

Parasomnias are undesirable but not always pathological events. They consist in abnormal behaviors during sleep due to the inappropriate activation of the cognitive process or physiological systems, such as the motor and/or autonomic nervous system. For this reason, parasomnias are conditions constituting a window into brain function during sleep. Non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep parasomnias are recurrent abnormal behaviors emerging as incomplete arousals out of NREM sleep. NREM parasomnias are common in the general population, occurring more frequently in children, but they could persist more frequently than expected during adulthood, with a lifetime prevalence of about 7%. When episodes are frequent, NREM parasomnias can result in sleep disruption and injuries with adverse health or psychosocial consequences for the patients, bedpartners, or both. It is, thus, necessary for clinicians to recognize, evaluate, and manage these sleep disorders, especially in adulthood. Many problems hamper a differential diagnosis between non-REM parasomnias and epileptic seizures occurring during sleep. In this article, the authors describe the characteristics of the NREM parasomnias, suggesting the key points for a decisive diagnostic workup.

|

• The large number of parasomnias underscores that sleep is not simply a quiescent state but can involve more or less complex behaviors. | |

|

• NREM parasomnias are usually benign phenomena, but sometimes and especially in adulthood they could lead to injuries affecting not only the patient but also the bed partner. | |

|

• Parasomnias must be distinguished from epileptic seizures arising from sleep. | |

|

• Video-polysomnography remains the most useful support for the final diagnosis. |

Parasomnias have attracted the interest of writers and scholars for centuries. Their sometimes dramatic manifestations have been described by many. Perhaps the most famous literary examples of parasomnia are the sleepwalking and sleeptalking events by Lady Macbeth in Shakespeare's Macbeth, Moncrieff’s Somnambulist, a play regarding a nighttime walking phantom, and Bellini's La Sonnambula, an innocent girl who suffers from a quirk of nature, hence, eliciting sympathy and compassion. In the novel Tess of the d'Urbervilles Thomas Hardy describes one of the most fascinating and convincing scenes of sleepwalking ever written (58).

According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3-TR) parasomnias are characterized as a group of "undesirable physical events or experiences that occur during entry into sleep, within sleep, or during arousals from sleep" (01). Some are associated with violent motor and autonomic activity, whereas others, such as sleep enuresis, have minimal muscle disturbance. Parasomnias may be categorized in various ways. The ICSD-3-TR divides parasomnias into four categories: (1) NREM- related parasomnias, including disorders of arousal (confusional arousals, sleep terror, and sleepwalking), and sleep-related eating disorder; (2) REM-related parasomnias, including nightmare disorder, recurrent isolated sleep paralysis, and REM sleep behavior disorder; (3) other parasomnias, including exploding head syndrome, sleep-related hallucinations, sleep enuresis, parasomnia unspecified, parasomnia due to drug or substance, and parasomnia due to medical conditions; and (4) isolated symptoms and normal variants including sleep talking (01).

The disorders of arousal, a common subset of NREM parasomnias, are based on the fundamental hypothesis that incomplete arousals occur because of disturbed or immature mechanisms of arousal (10; 03; 64). The disorders typically occur during the deepest stage of NREM sleep (slow-wave sleep), usually within 1 to 2 hours after sleep onset, only once a night. Patients may exhibit a wide variety of behaviors that include some ability to interact with their environment (03). The level of consciousness, amnesia, and sensory disconnection during non-REM parasomnia episodes is variable and graded (62). Typically, these patients have no memory of the events, but they may remember fragments, flashes, vague impressions of the events, or, rarely, “dreams” that are shorter and more fragmentary than REM sleep dreams (09; 53; 49; 62). Sometimes disorders of arousal appear to involve the disinhibition of “basic drive states” such as feeding, aggression, and sex (17; 64).

Disorders of arousal (DoA) have been arbitrarily divided into three types, depending on the complexity of their features: confusional arousals, sleep terrors, and sleepwalking.

Confusional arousals are frequent during childhood and consist of partial awakenings in which the state of consciousness remains impaired, and the subject is disoriented in time and space. Although appearing alert, with eyes open, the subject typically does not respond, and more forceful attempts to intervene or to console may meet with resistance and increased agitation (53). The parents are often very alarmed and make vigorous attempts to wake the child, prolonging the episode. If the child is woken, he or she is likely to be confused and frightened. Each episode usually lasts 5 to 10 minutes before the child calms down spontaneously and returns to restful sleep (53). Most of the time, confusional arousal is idiopathic, but sometimes, particularly in adults, it is associated with other sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, restless legs syndrome, idiopathic hypersomnia, and narcolepsy. Confusional arousal may also occur secondary to neurologic disorders involving periaqueductal gray, ascending reticular activating system and hypothalamus, as well as medical disorders.

Sleep terrors are sudden awakenings associated with vigorous motor behavior and strong autonomic responses. The episode may be heralded by a loud scream: the patient has an expression of extreme terror on his or her face, with staring eyes, and presents agitated behavior with crying, wriggling, struggling, sitting up in bed, calling out, or thrashing about. Autonomic activation is present with tachycardia, tachypnea, mydriasis, and profuse sweating. The episode usually lasts no more than a few minutes, ending abruptly with the patient settling back to sleep. If any recollection of the event is present, it is usually fragmented: the patient may describe a feeling of primitive threat or danger, but not offer the extended narrative that characterizes a nightmare.

During sleepwalking the subject may calmly walk around his or her room or into other parts of the house such as to the toilet, toward a light, or to his or her parents’ bedroom. The subject may appear downstairs or may be found standing on the landing or elsewhere in the house, looking vague with eyes open but with a glassy stare. At most he or she will be partially responsive. Episodes usually last from 5 to 15 minutes. Sleepwalkers experience a significant increase in the frequency of somnambulistic episodes during post-deprivation recovery sleep (73). Febrile illness, sleep-related breathing disorders, hypnotics, and alcoholic beverages are other recognized triggers for sleepwalking (03). In adults, the presence of a physical injury, potentially harmful behaviors alerting the bed partner, or violence during disorders of arousal episodes are often one of the principal reasons for consulting a sleep specialist. Described behaviors include moving furniture, running out of bed, jumping from a window, escaping imaginary threats, driving, and so on (50).

Three specific motor patterns characterized by increasing intensity and complexity have been described in adult patients with disorders of arousal. Pattern I, also called simple arousal movements, is characterized by head flexion or extension (Pattern IA), head flexion or extension and limb movement (Pattern IB), or head flexion or extension and partial trunk flexion or extension (Pattern IC). Pattern II, also called rising arousal movements, is characterized by a complete trunk flexion with patient sitting up in bed. Pattern III, also called complex arousal with ambulatory movements, is characterized by sleepwalking. Although these episodes are characterized by different complexity, they are preceded by a similar EEG activation at spectral analysis, implying that they possibly share a similar pathophysiology (48). Onset is abrupt in more than half of the episodes; in one study, episodes lasted 33 ± 35 seconds as a mean (± standard deviation) (39).

A case-control study comparing 52 adult patients with disorders of arousal versus 52 participants without disorders of arousal found that two or more N3 interruptions containing eye opening yielded a sensitivity of 94.2% and a specificity of 76.9% for a disorders of arousal diagnosis (04).

Sleep-related eating disorder consists of recurrent episodes of involuntary or “out-of-control” eating and drinking during arousals from sleep (01).

Nocturnal enuresis (bedwetting) refers to the passing of urine when asleep and may occur during NREM and REM sleep. Primary enuresis refers to enuresis in a child who has never been dry consistently since birth; secondary enuresis is applicable to a child who has had at least 6 months of dryness prior to recurrence of enuresis (55). Enuresis is a clinically and pathogenetically heterogeneous disorder. Children with nocturnal polyuria, with or without vasopressin deficiency, respond favorably to antidiuretic treatment and don’t present daytime bladder dysfunctions. On the other hand, nonresponders to antidiuretic therapy could suffer from detrusor overactivity, responding well to detrusor relaxant treatment and showing daytime symptoms such as urgency or incontinence. In some cases, children exhibit signs of both diuresis and detrusor dependency (55). Usually, enuretic children show a high comorbidity with other sleep disturbances like sleep disordered breathing and parasomnias (02) but a low incidence of disorder in initiating or maintaining sleep. This is consistent with the parental perception of a more deep sleep and a high arousal threshold in enuretic children.

Sleep talking may occur during REM or NREM sleep and can be idiopathic or associated with other parasomnias.

Disorders of arousal usually occur in children (01) and could be associated with a higher risk of sleep onset delay independently of sleep duration as documented in two cross-sectional studies conducted among 21,704 children (45).

Sometimes arousal disorders can persist into adulthood, or more rarely, may appear de novo in adults (46; 50; 53). In chronic sleepwalkers, sleep mentation associated with somnambulistic episodes increases with age, and episodes worsen in frequency and severity from childhood to adulthood (35). A higher frequency of sleepwalking during adulthood seems to increase the chance of violent episodes, and there is a male prevalence among disorders of arousal subjects with violent episodes referred to sleep centers (50). Parasomnias, emerging from NREM or REM sleep or from sleep-wake transitional states, are the most common sleep disorders responsible for violent sleep-related behaviors. A systematic review reported that homicides during DOA episodes, though rare, are documented, validating the parasomnia defense’s use in forensic medicine. RBD-related fatal aggression seems very uncommon (12).

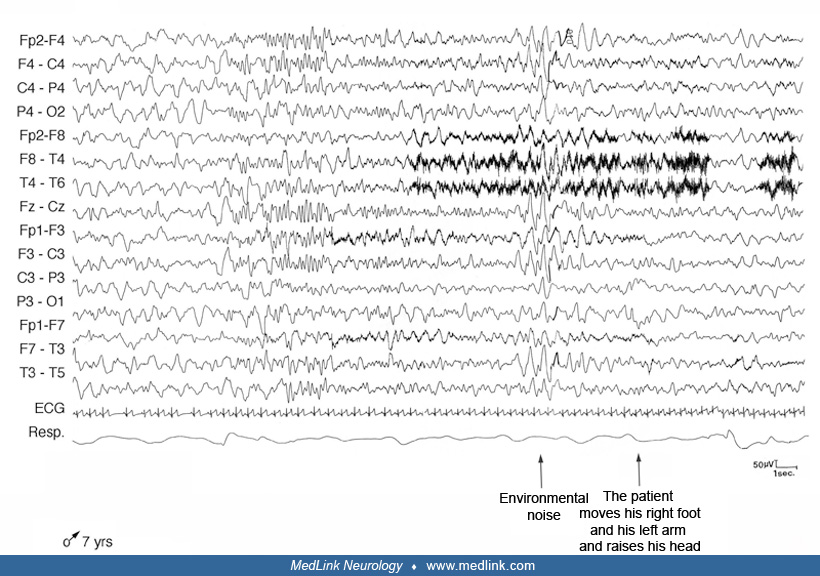

A 7-year-old boy presented with a 5-year history of sudden awakenings, usually in the first part of the night. The child’s medical history was unremarkable. Family history revealed that the patient’s sister experienced sleep enuresis and bruxism and a paternal aunt suffered from nightmares. His mother’s uncle had experienced sleepwalking during childhood.

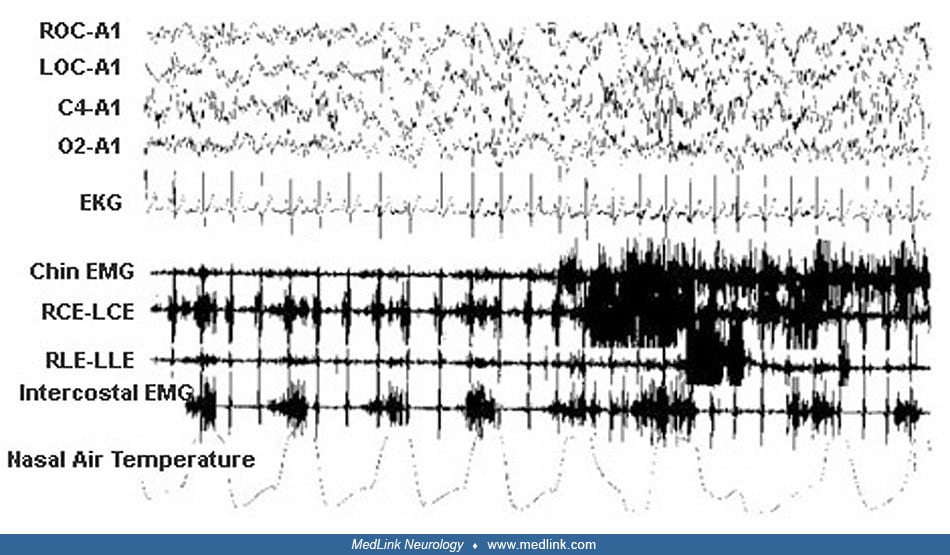

During nocturnal episodes the patient sat up, sometimes with a fearful expression, opened his eyes, moved his limbs, walked around or ran, screamed, and vocalized or uttered incomprehensible speech. He was pale with tachycardia and perspiration. He was unresponsive to external stimuli, rebelling if kept restrained. At the end of the episode the patient returned to his bed to sleep. Morning amnesia for the events was the rule. The episodes occurred weekly or monthly, lasting some minutes. Neurologic examination was negative; the child showed tonsillar hypertrophy. Video-polysomnography documented some nonstereotypical arousals from NREM sleep during which the patient raised his head and trunk from the bed with eyes closed, rubbing his nose.

The patient also presented snoring associated with obstructive hypopneas and apneas more often during REM sleep. Based on the characteristic history and on polygraphic findings, he was diagnosed with disorder of arousal. No pharmacologic treatment was begun, and his parents were reassured that the episodes are generally self-limiting, ceasing during adolescence. We advised tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy because obstructive sleep apnea could be a precipitant factor for the episodes.

Neuropathologic abnormalities are not present or have not been identified for most of the common parasomnias. A common motor dysregulation has been hypothesized in sleepwalking and REM sleep behavior disorder (29). Many of the NREM sleep parasomnias are thought to be due to a disturbance of arousal, in particular, an impaired ability to arouse fully from slow-wave sleep (28; 64).

The increase in the frequency of somnambulistic episodes during post-deprivation recovery sleep supports the view that sleepwalkers suffer from a dysfunction of the mechanisms responsible for sustaining stable slow-wave sleep (72; 47). Many investigators have looked at EEG findings to explain these parasomnias (08). Slow-wave activity and slow oscillation density were significantly greater prior to patients' somnambulistic episodes as compared with nonbehavioral awakenings. Yet, these disorders may represent activation of thalamocingulate pathways with disconnection of thalamocortical pathways (05) and could be the expression not of a global cerebral phenomenon, but rather of the coexistence of different local states of being (67). Scalp EEG analysis of 15 adult subjects with sleep arousal disorders showed that NREM sleep had a localized decrease in slow-wave activity power (1-4 Hz) over centro-parietal regions compared to good sleeping healthy controls. Source modelling analysis of 5-minute segments taken from N3 during the first half of the night revealed that the local decrease in slow-wave activity power was prominent at the level of the cingulate, motor, and sensorimotor associative cortices. These differences in local sleep were present in the absence of any detectable clinical or electrophysiological sign of arousal, showing that the disorder could be due to local arousals in motor and cingulate cortices (11). An increase in delta activity occurring predominantly in frontal regions was found in 19 episodes of confusional arousals in five drug-resistant epileptic patients suffering incidentally from arousal disorders (23). Using 256-channel-EEG in nonepileptic patients, Ratti and colleagues confirmed and expanded these data, highlighting a putative role of right rPFC and prefronto-temporal circuit in disorders of arousal (60). Comparing regional brain activity, measured with high-density EEG, in parasomnia episodes and normal awakenings, parasomnia episodes occurred on a less-activated EEG background and displayed higher slow-wave activity and lower beta activity in frontal and central brain regions after movement onset (14).

Thus, the traditional idea of somnambulism as a disorder of arousal might be too restrictive, and a comprehensive view should include the idea of simultaneous interplay between states of sleep and wakefulness (72; 64). When compared to controls' brain perfusion patterns with a high-resolution SPECT scanner, sleepwalkers showed reduced regional cerebral perfusion in frontal and parietal regions during both slow-wave sleep and resting-state wakefulness (20).

A variety of factors may precipitate NREM parasomnias in susceptible individuals. Major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder were associated with a significant greater risk of sleepwalking in adults. Stress, sleep deprivation, and working rotating shifts are common triggers of NREM parasomnias, as well as prescription or nonprescription drug use (13; 47; 27; 49). Medications that can cause sleepwalking include neuroleptics, hypnotics, lithium, amitriptyline, beta-blockers, and topiramate. Other sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea or periodic limb movements, may trigger parasomnia events in both adults and children. Finally, there is growing evidence that strong familial aggregation and genetic factors are involved in the occurrence of NREM parasomnias, particularly sleep terrors and sleepwalking (36; 59; 46). A study of 56 patients with NREM parasomnias confirmed a high prevalence of the HLA DQB1*05:01 genotype in all types of NREM parasomnias, underlying their common genetic background (31). Data from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort of 7515 youths aged between 8 and 22 years documented a correlation between lifetime history of sleepwalking and male sex and European-American race (16). A genetic risk locus that reached genome-wide significance was detected at rs73450744 on chromosome 18 in African Americans.

The description of sleep terrors and symptoms of REM sleep behavior disorder in two siblings with a novel homozygous variant of the GLRA1 gene causing hereditary hyperekplexia suggests that impaired glycinergic transmission in human hereditary hyperekplexia could be involved in the pathophysiology of REM sleep behavior disorder and NREM parasomnias (43).

Nocturnal enuresis is highly heritable. In a genome-wide association study on a large Danish population-based case cohort, two loci at chromosomes 6 and 13 were significantly associated with nocturnal enuresis (34).

The first systematic investigation of EEG correlates of sleep talking documents it as a direct manifestation of language processing, with a functional and topographical correspondence with dreamt and planned language production (51).

|

• The incidence of parasomnias is highly variable and depends on the particular disorder (01). | |

|

• NREM parasomnias are more common in childhood than in adulthood. | |

|

• The prevalence of sleep-related eating disorder is not clear because several epidemiological studies have been conducted targeting relatively small and specific populations. | |

|

• Sleep enuresis is the second most common complaint in childhood. |

Many of the parasomnias are more common in childhood than in adulthood. Approximately 30% of children and 2% to 5% of adults have sleepwalking or sleep terrors; sleepwalking is common between the ages of 3 and 13 years, and most episodes resolve after the age of 10 years. In some cases, disorders of arousal persist or arise also in older adults, with a motor patterns similar to those of younger patients (37). NREM parasomnias have also been described in Machado-Joseph disease and in Parkinson disease (63). In a systematic review including more than 100,000 subjects from 51 studies, the estimated lifetime prevalence of sleepwalking was 6.9% (95% CI 4.6%-10.3%) (65). The current prevalence rate of sleepwalking--within the last 12 months--was significantly higher in children (5.0%) (95% CI 3.8%-6.5%) than in adults (1.5%) (95% CI 1.0%-2.3%) (65).

The prevalence of sleep-related eating disorder in a sample of patients who had been referred to a sleep disorders clinic over a 7-year period was 0.5%. In another study, 16.7% of inpatients and 8.7% of outpatients with eating disorders were reported to have behaviors consistent with sleep-related eating disorder (69; 32). In a cross-sectional web-based survey on 3347 Japanese young adults aged 19 to 25 years, 160 (4.8%) reported experiencing nocturnal eating behavior and 73 (2.2%) reported experiencing sleep-related eating disorder-like behavior (52). Smoking (p < 0.05), use of hypnotic medications (p < 0.01), and previous or current sleepwalking (p < 0.001) were associated with both nocturnal eating behavior and sleep-related eating disorder-like behavior.

A study of 1318 psychiatric outpatients taking hypnotics revealed that 8.4% had experienced sleep-related eating disorder. The sleep-related eating disorder group was significantly younger, had a significantly higher total Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score, and took higher bedtime diazepam-equivalent doses of hypnotics than the non-sleep-related eating disorder group (P < .01 for all comparisons) (66).

In children less than 5 years of age, nocturnal enuresis is normal. It has been estimated that at 5 years, approximately 15% to 25% of children have nocturnal enuresis (55). Enuresis is frequently observed in children with attention deficit and hyperactivity or impulsivity disorder (19).

Arousal disorders can be embarrassing to sufferers themselves, especially if they occur away from home, and sleepwalkers can experience daytime somnolence (54). Accidental injury in sleepwalking (eg, from falling downstairs or crashing through windows or a glass door) is a substantial risk; the wandering may extend further within the house or outside. Patients with nocturnal events and their bed partners need to be protected from potential harm (03; 49). Therefore, it is important to make the environment as safe as possible to reduce the risk of injury (eg, remove obstructions in the bedroom, secure windows, install locks or alarms on outside doors, cover windows with heavy curtains, sharp or dangerous objects need to be stored safely away) (07; 53). In any case, the primary prevention of nocturnal events, in particular NREM parasomnias, is based on reducing stress, improving sleep hygiene, ensuring regular and adequate sleep routines, and avoiding sleep loss or deprivation and cognitive impairing substances (13). Individuals who are predisposed to a disorder of arousal may have events as a symptom of another sleep disorder, such as sleep apnea. In these cases, the parasomnia disappears after treatment of the primary sleep disorder. Finally, it is necessary to reassure parents that these often frightening nocturnal events do not mean that the child is ill or disordered and that she or he can be expected to grow out of them. Trying to waken or restrain the child during the episode is difficult, counterproductive, and unnecessary.

Being bullied increases the risk of parasomnias in children. Parents, teachers, and clinicians may consider asking about bullying experiences if a child is having parasomnias, and in particular nightmares and sleep terrors (71).

The differential diagnosis of parasomnias depends largely on the symptoms and signs associated with the particular disorder. Evaluation requires special emphasis on a detailed description of the nocturnal events, including age at onset, the spontaneous evolution of the episodes, the frequency of occurrence of the episodes during the night, the timing, the presence of stereotypical movements, the response to intervention, and recall of the event (53). Sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy should be deemed much more likely than a sleep arousal disorder if attacks recur several times during the same night; if they occur in a stereotypical fashion; if they arise or persist into adulthood; and if tremor, dystonia, ballism, or other abnormal movements are present during the episode (68). Medications and drugs causing cognitive impairment need to be considered as sources for confusional arousals. Conditions associated with nocturnal pain may be a factor, particularly in patients such as infants or retarded individuals who cannot describe their symptoms.

The diagnostic workup is highly contingent on the type and frequency of symptoms (53; 26). Many parasomnias can be diagnosed on the basis of the history and physical examination. The ICSD-3-TR criteria are adequate for a reliable diagnosis of disorders of arousal (40; 38). Some authors have proposed a revision of the current diagnostic criteria, highlighting the limits of several clinical criteria, which should rather be supportive features than mandatory criteria (41). Yet the clinician needs to delineate between a “benign” parasomnia and a nocturnal event that requires further investigation. Patients should be considered for polysomnographic evaluation if the presentation is atypical for a parasomnia or if:

|

• the events are injurious or have significant potential for injury |

Sleep laboratory evaluations may include one or two nights of recording in a laboratory with personnel experienced in studying patients with parasomnias or nocturnal epileptic seizures. Simultaneous polysomnographic-audio-video monitoring is essential for such recordings, often with additional physiological measures beyond the minimum required for standard polysomnography (24; 53; 49). Strong evidence supports the use of sleep deprivation in facilitating the occurrence of somnambulistic events in the sleep laboratory (06). Prompting the patient to make audio-video recordings at home may facilitate the diagnosis, often adding details that are missed in verbal descriptions given by relatives. Patients should be considered for video-EEG monitoring if the events are stereotypic or repetitive, occur frequently (minimum of one event per week), or have not responded to medication trials, and the history is suggestive of potentially epileptic events. Slow-wave sleep fragmentation and frequent slow or mixed arousals in slow-wave sleep are strongly associated with NREM parasomnias and could be promising biomarkers for the diagnosis of disorders of arousal (44; 42).

Sleep-related dissociative disorders often reported as a “parasomnia mimic” must be distinguished from physiological sleep-wake dissociation as found in primary sleep behavior disorders. The objective diagnostic confirmation for sleep-related dissociative disorders consists of the hallmark finding of abnormal nocturnal behaviors arising from sustained electroencephalograhic wakefulness (61).

Management of arousal disorders often consists of reassurance that the nocturnal symptoms are benign and will likely improve with age. Patient education and nonpharmacologic treatment are important parts of therapy for arousal disorders. Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral treatments and mindfulness-based stress reduction have been employed successfully in parasomnias (25; 21; 13; 57; 26; 50). Stress management, counseling, and avoidance of cognitively impairing medications may improve the frequency of the events. Patients with the potential for injuring themselves or their families need to be counseled in methods to reduce risk of injury (protective material across windows, lack of access to potential weapons, etc.) (53). Patients with other underlying sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea or periodic limb movements, should have these disorders appropriately treated to decrease the potential for sleep disruption. Some patients require medication therapy for their nocturnal events. Patients with frequent NREM-related events may respond to clonazepam, which should be started at a dosage of 0.5 mg at bedtime and progressively increased up to 2 mg if necessary, as tolerated (18; 33).

First-line treatment of idiopathic sleep-related eating disorder includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), topiramate (100-300 mg/day), and clonazepam (0.5-2.0 mg/day) (15; 70; 33).

In enuretic children, active therapy is recommended from the age of 6 years. The most important comorbid conditions to take into account are psychiatric disorders, constipation, urinary tract infections, and snoring or sleep apnea. In nonmonosymptomatic enuresis, it is recommended that basic advice regarding voiding and drinking habits be provided. In monosymptomatic enuresis, or if the above strategy did not make the child dry, the first-line treatment modalities are desmopressin or the enuresis alarm. If both these therapies fail alone or in combination, anticholinergic treatment is a possible next step. If the child is unresponsive to initial therapy, antidepressant treatment may be considered by the expert. Children with concomitant sleep disordered breathing may become dry if the airway obstruction is removed (56).

Pharmacological treatment is not usually necessary in children with arousal disorders (07; 53). Benzodiazepines, like clonazepam and diazepam, and tricyclic drugs (imipramine) should be reserved for children and adults with severe and frequent episodes, when other measures have failed. Attention must be paid to the appearance of daytime sedation using benzodiazepines, especially those with long half-life (diazepam): the dose must be increased slowly. In children, satisfactory results have also been reported with L-5-hydroxytryptophan and melatonin.

Parasomnia events appear to decrease during pregnancy. The events had the greatest decrease in primipara women. Compared to the prepregnant period, sleepwalking decreased by over 40% in the second trimester (30).

All contributors' financial relationships have been reviewed and mitigated to ensure that this and every other article is free from commercial bias.

Federica Provini MD

Dr. Provini of the University of Bologna and IRCCS Institute of Neurological Sciences of Bologna received speakers' fees from Idorsia, Italfarmaco, and NeoPharmed Gentili Spa.

See Profile

Giuseppe Loddo MD

Dr. Loddo of AUSL Bologna received a consultant honorarium from Bruno Pharmaceutica and a congress registration fee from B2 Pharma.

See Profile

Antonio Culebras MD FAAN FAHA FAASM

Dr. Culebras of SUNY Upstate Medical University at Syracuse has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

See ProfileNearly 3,000 illustrations, including video clips of neurologic disorders.

Every article is reviewed by our esteemed Editorial Board for accuracy and currency.

Full spectrum of neurology in 1,200 comprehensive articles.

Listen to MedLink on the go with Audio versions of each article.

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Sleep Disorders

Jan. 18, 2025

Sleep Disorders

Dec. 03, 2024

General Neurology

Nov. 09, 2024

Sleep Disorders

Nov. 04, 2024

Sleep Disorders

Oct. 31, 2024

Sleep Disorders

Oct. 27, 2024

Sleep Disorders

Oct. 14, 2024

Sleep Disorders

Oct. 14, 2024