General Neurology

Use of focused ultrasound in neurologic disorders

Jan. 13, 2025

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Worddefinition

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas.

Pyridoxine, or vitamin B6, deficiency and toxicity can involve changes predominantly in hematologic, dermatologic, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and neurologic systems. Pyridoxine 5'-phosphate is an essential cofactor in various transamination, decarboxylation, glycogen hydrolysis, and synthesis pathways involving carbohydrate, sphingolipid, amino acid, heme, and neurotransmitter metabolism. Vitamin B6 is required for the production of serotonin and helps to maintain a healthy immune system, protect the heart from cholesterol deposits, and prevent kidney stone formation.

Neurologic disorders reflecting both pyridoxine deficiency and pyridoxine toxicity have been recognized. Both overdose and deficiency may cause peripheral neuropathy. Pyridoxine deficiency causes injury of motor and sensory axons, whereas an overdose of pyridoxine causes a pure sensory neuropathy or neuronopathy with sensory ataxia.

Some drugs, such as isoniazid and enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs, interfere with pyridoxine metabolism.

Several hereditary conditions disrupt pyridoxine metabolism, including pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy.

|

• Vitamin B6, also called pyridoxine, is one of eight water-soluble B vitamins. Pyridoxine acts as a coenzyme in the breakdown and utilization of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. | |

|

• Pyridoxine is essential in numerous biochemical pathways involving the nervous system, red blood cells, the immune system, protein metabolism, homocysteine metabolism, and the production of energy. | |

|

• Pyridoxine is important for maintaining healthy nerve and muscle cells and it aids in the production of DNA and RNA. | |

|

• The recommended daily dose of pyridoxine is 2.0 mg/day for adult men and 1.6 mg/day for adult women. Higher amounts may be recommended for certain conditions. | |

|

• Common sources of pyridoxine include brewer's yeast, carrots, chicken, eggs, fish, meat, peas, spinach, sunflower seeds, whole grains, bread, liver, cereals, spinach, green beans, and bananas. | |

|

• Symptoms of pyridoxine deficiency include neuropathy, confusion, dermatitis, and insomnia. | |

|

• Pyridoxine overdose causes a sensory neuronopathy characterized by poor coordination, numbness, and decreased sensation to touch, temperature, and vibration. | |

|

• Several hereditary conditions disrupt pyridoxine metabolism, including pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy and pyridoxamine 5'-phosphate oxidase deficiency (PNPOD). |

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) was discovered in 1934 by Hungarian-born American biochemist, nutritionist, and pediatrician Paul György (1893-1976) (206). At that time vitamin B6 was recognized as a new component of the vitamin B complex of water-soluble vitamins that cured a nutritional skin disorder of rats called “rat acrodynia.” Young rats kept on a semisynthetic diet with added vitamin B1 (thiamine) and B2 (riboflavin) developed severe skin lesions with edema, erythema, and scaliness affecting their paws, snout, nose, and ears. Using rat acrodynia as a bioassay, György and his colleagues successfully isolated and characterized vitamin B6. Vitamin B6 was subsequently isolated and crystallized by Samuel Lepkovsky (1899-1984) in 1938 (140) and first synthesized (by two different research groups) in 1939 (93; 129).

Between 1951 and 1954, hyperirritability and convulsive seizures developed in 54 infants fed formula that was later shown to be deficient in pyridoxine (53). This was recognized by pediatrician David B Coursin of St. Joseph's Hospital in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy was first described in 1954 by pediatrician Andrew D Hunt Jr and colleagues at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia (100).

Sensory neuronopathy from pyridoxine abuse was first recognized in the 1980s, initially by neurologist Herbert H Schaumburg and colleagues at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in 1983 (218).

|

• Pyridoxine deficiency can manifest with neurologic, dermatologic, cardiologic, gastrointestinal, and hematologic symptoms. | |

|

• Central nervous system symptoms of pyridoxine deficiency include depression, anxiety, irritability, confusion, generalized seizures, and white matter lesions. In addition, some patients have generalized weakness and dizziness. | |

|

• Pyridoxine deficiency causes a mixed distal symmetric polyneuropathy presenting as bilateral, distal limb numbness or pain and rarely distal limb weakness; examination is consistent with a large-fiber neuropathy. | |

|

• Adults with neuropathy due to pyridoxine deficiency may have reduced vibration sensation and proprioception with preserved pain and temperature sensation, as well as a sensory ataxia from large fiber involvement. | |

|

• Older patients with pyridoxine deficiency may have confusion, dementia, disorientation, rigidity, and primitive reflexes, whereas neurologic signs in neonates and young infants include hypotonia; irritability; restlessness; focal, bilateral motor, or myoclonic seizures; and infantile spasms. | |

|

• Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy usually manifests with a combination of seizure types in the first hours of life, which are unresponsive to standard anticonvulsants, but respond to immediate administration of pyridoxine hydrochloride. | |

|

• Vitamin B6 is usually safe, at doses up to 200 mg per day in adults. When taken at higher doses or over a long period of time, vitamin B6 can produce a range of nonspecific systemic symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, tachypnea, and rash. Patients may develop a neuropathy with distal sensory loss and paresthesias. | |

|

• Some patients with pyridoxine toxicity, particularly with mega doses of pyridoxine (ie, greater than 2 g/day), may develop a sensory neuronopathy with severe sensory loss throughout the body; the resulting loss of proprioception can produce a dramatic sensory ataxia. |

Pyridoxine deficiency can manifest with neurologic, dermatologic, cardiologic, gastrointestinal, and hematologic symptoms. Central nervous system symptoms include depression, anxiety, irritability, confusion, generalized seizures, and white matter lesions. In addition, some patients have generalized weakness and dizziness (40). Dermatologic symptoms include erythematous itching, burning, blisters, vesicles, hyperpigmentation, and thickening of skin, similar to that seen with vitamin B2 (riboflavin) and vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiencies. Gastrointestinal symptoms include nausea, diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and pain. Hematologic manifestations can include anemia, which most often presents with fatigue. Low-serum pyridoxal 5'-phosphate concentration has been associated with indicators of poor nutritional status and may be related to increased hemolysis in children with sickle cell disease (177).

Pyridoxine deficiency causes a mixed distal symmetric polyneuropathy presenting as bilateral, distal limb numbness or pain and rarely distal limb weakness. Examination is consistent with a large-fiber neuropathy.

Adults with neuropathy may have reduced vibration sensation and proprioception with preserved pain and temperature sensation, as well as a sensory ataxia from large fiber involvement. In addition, older patients may have confusion, dementia, disorientation, rigidity, and primitive reflexes. In neonates and young infants, neurologic signs include hypotonia; irritability; restlessness; focal, bilateral motor, or myoclonic seizures; and infantile spasms. Additional physical examination findings in pyridoxine deficiency may include glossitis, cheilosis, and seborrheic dermatitis. Multiple cooccurring nutritional deficiencies may act synergistically with pyridoxine deficiency to produce a devastating neuropathy.

Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy usually manifests with a combination of seizure types (including myoclonic seizures, infantile spasms, and status epilepticus) in the first hours of life, which are unresponsive to standard anticonvulsants, but respond to immediate administration of pyridoxine hydrochloride (193; 239). Additional manifestations may include excessive irritability, tremulousness, and poor psychomotor development. Interruption of daily pyridoxine supplementation results in recurrence of seizures. Some patients show developmental delay. Rare later-onset cases have also been reported, with progressively worsening, treatment-refractory seizures beginning at 14 months of age (69).

Several studies have noted a high frequency of pyridoxine deficiency in patients with established (benzodiazepine-resistant) status epilepticus. A retrospective cohort study of 293 hospitalized patients with established status epilepticus found that these patients had a significantly higher prevalence of marginal and deficient pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) levels (90 and 80%, respectively) than patients in each of the three control groups (ie, intensive care unit patients without status epilepticus, non–intensive care unit inpatients without status epilepticus, and outpatients with or without a history of epilepsy) (208). This significantly higher prevalence persisted after correcting for critical illness severity and timing of PLP level collection.

In a prospective case series of 30 adults with epilepsy categorized by level of control (based on the crude metric of a seizure within the prior 3-month period), "poorly controlled" individuals had significantly lower serum pyridoxine levels (196).

Toxicity. Vitamin B6 is usually safe, at doses up to 200 mg per day in adults, although a case of pyridoxine toxicity-related peripheral neuropathy has been reported with daily multivitamin use (6 mg of pyridoxine daily) (184). When taken at higher doses or over a long period of time, vitamin B6 can produce a range of nonspecific systemic symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, tachypnea, and rash. Patients may develop a neuropathy with distal sensory loss and paresthesias (174; 184). Muscle weakness and rhabdomyolysis have been described in a few patients, and Achilles reflexes are typically lost (11). An infant with homocystinuria due to a deficiency of cystathionine beta-synthase was given a pyridoxine challenge with high-dose pyridoxine to determine responsiveness but developed respiratory failure and rhabdomyolysis consistent with pyridoxine toxicity, highlighting the need for weight-based dosing and duration recommendations for pyridoxine challenge in neonates (11).

Some patients with pyridoxine toxicity, particularly with mega doses of pyridoxine (ie, greater than 2 g/day), may develop a sensory neuronopathy with severe sensory loss throughout the body (235; 218; 186; 56; 07; 57; 06; 157; 134; 62; 77; 37; 131). Loss of proprioception can produce a dramatic sensory ataxia.

Pyridoxine has the highest rate of adverse outcomes per toxic exposure for any vitamin, although no deaths have been reported.

Both pyridoxine deficiency and excess may cause peripheral neuropathy. The neuropathy associated with pyridoxine deficiency may improve with pyridoxine replacement or when responsible medications that interfere with pyridoxine metabolism (eg, isoniazid) are stopped, but the neuropathy may not completely resolve.

Despite medical management, patients with pyridoxine-dependent seizures may have developmental delay, particularly in expressive language.

Injecting pyridoxine into an infant or neonate can cause a precipitous decrease in blood pressure (85).

Deficiency of pyridoxine can cause hyperoxalemia and hyperoxaluria in patients with chronic kidney disease, potentially compounding kidney dysfunction (175).

Inadequate B6 levels have been linked to an increased risk of age-related chronic diseases (eg, cardiovascular disease and cancer), sarcopenia (ie, age-related loss of muscle mass and strength), frailty (ie, a decline in physiological resilience and increased vulnerability associated with aging), and all-cause mortality in adults (118). Proposed mechanisms involve P2X7 receptor-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome signaling, AMPK signaling, PD-L1 signaling, and satellite cell-mediated myogenesis (118). In addition, B6 deficiency–associated modulation of PLP-dependent enzymes impairs energy utilization and affects imidazole peptide production and hydrogen sulfide production, as well as the kynurenine pathway, which can all impact skeletal muscle health.

Pyridoxine blocks lactation and inhibits the secretion of breast milk in nursing mothers by suppressing the normally elevated prolactin hormone levels encountered during the puerperium (87).

With neuropathy associated with pyridoxine toxicity, complete recovery may occur in patients with a mild neuropathy who have been taking only low doses of the vitamin (117). The sensory neuronopathy caused by pyridoxine overdose shows little improvement. Sensory neuronopathy from pyridoxine overdose can begin approximately 1 month to 3 years following supplementation. Although this usually occurs at very high supplementation doses, complications have been reported with doses as low as 50 mg/d (220).

|

• Pyridoxine is obtained from two exogenous sources: (1) a dietary source, which is absorbed in the small intestine; and (2) a bacterial source, where the vitamin is synthesized in significant quantities by the normal microflora of the large intestine. | |

|

• Pyridoxine is absorbed by a specific and regulatable carrier-mediated process for pyridoxine uptake by mammalian colonocytes. | |

|

• Pyridoxine is utilized by the liver to synthesize pyridoxal 5'-phosphate, which functions as a coenzyme in transamination and decarboxylation reactions involved in amino acid and protein metabolism, and also as a coenzyme in the biosynthesis of heme, niacin, and serotonin. | |

|

• Pyridoxal deficiency can contribute to a metabolic deficiency of niacin and the clinical disorder pellagra. | |

|

• Clinically manifest dietary pyridoxine deficiency is rare, though medical conditions or procedures can increase the risk for pyridoxine deficiency, including celiac disease, renal dialysis, total parenteral nutrition, severe malnutrition, rheumatoid arthritis, alcoholism, alcoholic liver disease, subacute hepatic necrosis, and sickle cell disease. | |

|

•Drugs can cause clinical manifestations of pyridoxine deficiency if they either react with pyridoxal phosphate or affect the metabolism of B6 vitamers. | |

|

• Inherited disorders of pyridoxine metabolism include inborn errors that lead to accumulation of small molecules that react with pyridoxal phosphate and inactivate it, inborn errors that affect the pathways of pyridoxine metabolism, and inborn errors that affect specific pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzymes. | |

|

• Sensory neuronopathy (and less commonly a sensorimotor neuropathy) may develop in patients who consumed high doses of pyridoxine; pyridoxine given in large doses selectively destroys large-diameter peripheral sensory nerve fibers, leaving motor fibers intact. |

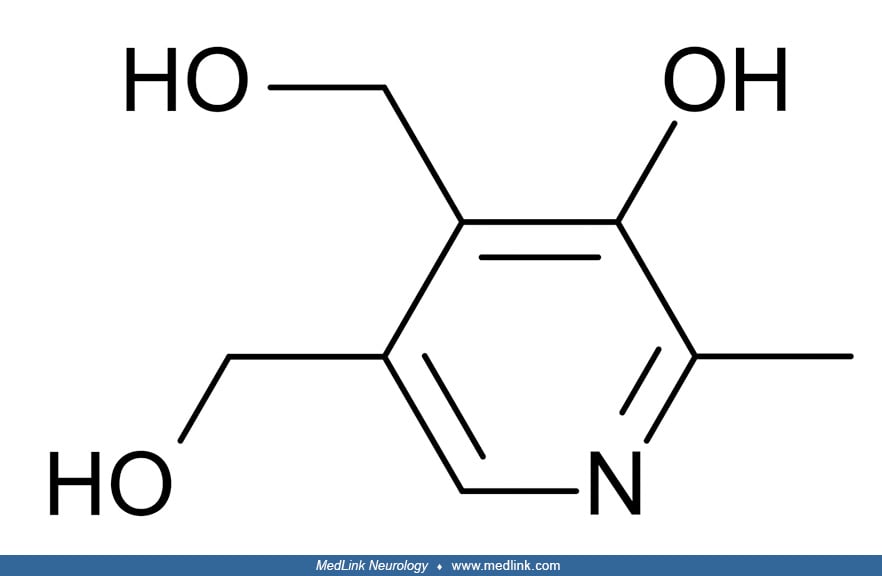

Biochemistry and metabolism. Vitamin B6 or pyridoxine is a complex of six vitamers: pyridoxal, pyridoxine (pyridoxol), pyridoxamine, and their respective 5'-phosphate esters, pyridoxal 5'-phosphate, pyridoxine 5'-phosphate, and pyridoxamine 5'-phospate. Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate is the active coenzyme form and has the most importance in human metabolism.

Pyridoxine is obtained from two exogenous sources: (1) a dietary source, which is absorbed in the small intestine; and (2) a bacterial source, where the vitamin is synthesized in significant quantities by the normal microflora of the large intestine (211). Pyridoxine is absorbed by a specific and regulatable carrier-mediated process for pyridoxine uptake by mammalian colonocytes (211).

Pyridoxine is utilized by the liver to synthesize pyridoxal 5'-phosphate. Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate functions as a coenzyme in transamination and decarboxylation reactions involved in amino acid and protein metabolism. Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate also acts as a coenzyme in the biosynthesis of heme and multiple neurotransmitters.

Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate is a coenzyme that is necessary for methionine metabolism. With pyridoxine deficiency-induced methionine deficiency, S-adenosylmethionine accumulates, resulting in the inhibition of sphingolipid and myelin synthesis.

Homocysteine metabolism is dependent on pyridoxine, and high homocysteine levels can result from pyridoxine deficiency. In combination with folic acid and vitamin B12, vitamin B6 lowers levels of homocysteine, an amino acid linked to heart disease and stroke and possibly to other diseases, such as osteoporosis and Alzheimer disease.

Tryptophan is a precursor to several neurotransmitters and is required for niacin production. Pyridoxine is a cofactor in the transformation of tryptophan to niacin (143). In the presence of pyridoxal phosphate deficiency, tryptophan is diverted instead to xanthurenic acid, which is excreted in the urine. Consequently, pyridoxal deficiency can contribute to a metabolic deficiency of niacin and the clinical disorder pellagra (154; 50; 102).

The neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, glycine, glutamate, and GABA also require pyridoxal 5'-phosphate for their production. Pyridoxal phosphate is a cofactor for the enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase, which is required for the production of monoamine neurotransmitters (ie, serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine). Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase is responsible for converting the precursors 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) into serotonin and levodopa (L-dopa) into dopamine (which is subsequently converted by other enzymes into norepinephrine and epinephrine). Pyridoxal phosphate is also a cofactor for the enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase, which is required for the formation of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) from glutamic acid. Therefore, pyridoxal phosphate deficiency alters the balance between inhibitory GABAergic and excitatory glutaminergic neurotransmission, which can lead to seizures.

After absorption, pyridoxine, pyridoxamine, and pyridoxal are transported into hepatic cells by facilitated diffusion. Pyridoxal kinase phosphorylates pyridoxine and pyridoxamine, after which they are converted to pyridoxal 5'-phosphate by a flavin-dependent enzyme. Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate either remains in the hepatocyte, where it is bound to an apoenzyme, or it is released into the serum, where it is tightly bound to lysine residues of proteins, mostly albumin. Free pyridoxal is degraded by alkaline phosphatase, hepatic and renal aldehyde oxidases, and pyridoxal dehydrogenase. Excessive intake of pyridoxine may saturate either of these enzyme systems, with a resultant accumulation of (inactive) pyridoxine, which occupies binding sites on the appropriate apoenzymes and, thus, acts as a competitive inhibitor for pyridoxal phosphate. In essence, an excess or overdose of pyridoxine leads to a deficiency of pyridoxal phosphate.

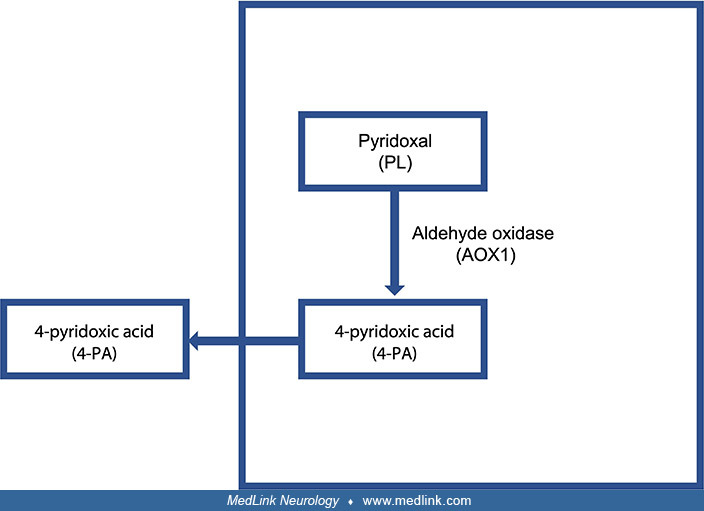

The vitamin B6 salvage pathway. The different vitamers are converted into pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) through the “B6 salvage pathway,” which involves the enzymes pyridoxal kinase (PDXK), pyridoxine 5′-phosphate oxidase (PNPO), and pyridoxal phosphatase (PDXP) (90). To enter a cell, phosphorylated vitamers are hydrolyzed by tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (ALPL). Once inside the cell, PDXK phosphorylates the different vitamers, yielding pyridoxine-5’-phosphate (PNP), pyridoxamine 5’-phosphate (PMP), and pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP). PMP and PNP are converted into PLP by pyridoxine 5′-phosphate oxidase (PNPO). Transaminases may also interconvert PMP and PLP. Pyridoxal phosphatase (PDXP), along with other phosphatases, hydrolyze phosphorylated vitamin B6 vitamers, enabling them to exit the cell. Pyridoxal is eliminated from the body following its conversion to 4-pyridoxic acid (4-PA), which is catalyzed by aldehyde oxidase (AOX1).

Pyridoxine deficiency. At the recommended dietary allowance for most Americans, substantial proportions of some population subgroups do not meet accepted criteria for adequate vitamin B6 status (169; 170). Nevertheless, clinically manifest dietary pyridoxine deficiency is rare, though medical conditions or procedures can increase the risk for pyridoxine deficiency. Such conditions include celiac disease (which causes malabsorption of B6 vitamers), renal dialysis (which increases losses of B6 vitamers from the circulation), total parenteral nutrition (which may fail to include sufficient B6 vitamers in the infusion), as well as severe malnutrition, rheumatoid arthritis, alcoholism, alcoholic liver disease (including decompensated cirrhosis), subacute hepatic necrosis, and sickle cell disease (146; 257; 60; 168; 136; 147; 160; 161; 40; 41; 48; 91; 232). Alcoholism-induced pyridoxine deficiency may exacerbate seizures and prove intractable to anticonvulsants until pyridoxine has been repleted (232). Pyridoxine metabolism in sickle cell disease may be disturbed as a function of riboflavin status (02) and may vary across different tissues (176). Although pyridoxine deficiency can develop in persons of any age, elderly persons are at increased risk (169; 270).

At one institution, among patients with documented pyridoxine levels, pyridoxine deficiency was seen in 94% of adult patients with status epilepticus compared to 39% of outpatients with epilepsy, suggesting a causal relationship between pyridoxine levels and status epilepticus (61). To validate this finding, a prospective study is needed in which all cases of status epilepticus have pyridoxine levels determined.

Medication- or toxin-induced pyridoxine deficiency. Drugs can cause clinical manifestations of pyridoxine deficiency if they either react with pyridoxal phosphate or affect the metabolism of B6 vitamers (137; 48). For example, medication-induced pyridoxine deficiency may be caused by antituberulosis drugs isoniazid (INH or isonicotinic hydrazide) and pyrazinamide and by enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (167), carbidopa (202; 268; 274), hydralazine (197), cycloserine (152), carboplatin (243; 217), and D-penicillamine. Different studies have reported divergent results in terms of any effects of oral contraceptives on pyridoxine levels (139; 163; 205; 14; 30; 30; 263; 51).

Pyridoxine has been used as an antidote in acute intoxications, including Gyromitra mushroom or false morel (monomethylhydrazine) poisoning (142; 138). In the stomach, gyromitrin is metabolized to monomethylhydrazine, which is the active metabolite responsible for inhibiting many enzymatic processes, particularly by the inhibition of pyridoxine.

Isoniazid. Patients treated with isoniazid for tuberculosis (or for conversion of a tuberculin skin test)—an agent that inhibits pyridoxine phosphorylation—may develop peripheral neuropathy due to pyridoxine deficiency if they do not take supplemental pyridoxine (207; Badrinath and John 2024). Isoniazid serves as a prodrug that undergoes metabolic activation by a mycobacterial enzyme and then interferes with the mycobacterial synthesis of mycolic acids (very long-chain lipids that are important components of mycobacterial cell walls); consequently, isoniazid is a potent tuberculostatic agent. Isoniazid was first made available in 1952, but soon there were numerous reports of neurotoxicity related to the use of isoniazid (23; 75), including particularly peripheral neuropathy, which may be painful (110; 144; 24; 25; 13; 99; 148; 255) and seizures (82). Peripheral neuropathy is significantly higher among slow than among rapid inactivators of isoniazid (254). Other studies documented other manifestations of isoniazid neurotoxicity, including optic neuropathy (119; 116; 115; 76; 108; 84; 125; 124; 181; 132), confusion (200), encephalopathy (01), toxic psychosis (04), obtundation and coma (82; 32; 47), and a cerebellar syndrome (27).

Peripheral neuropathy was recognized as a particularly frequent side effect of isoniazid therapy, affecting approximately 40% of patients in early studies (24; 25). Similarities of isoniazid-related neuropathy to that produced by the pyridoxine antagonist, desoxypyridoxine, led Biehl and colleagues to investigate the effect of isoniazid on pyridoxine metabolism in the early 1950s. They found a dose-effect relationship between dose of isoniazid administered and the frequency of peripheral neuropathy in patients and an inverse relationship between dose and time to development of toxic manifestations. Furthermore, they found that concurrent administration of pyridoxine could prevent the development of peripheral neuropathy even with large doses of isoniazid.

Further studies demonstrated that isoniazid interferes with the metabolism of pyridoxine (vitamin B6) (233). The principle biologically active form of pyridoxine (vitamin B6) is pyridoxal 5'-phosphate, which can form a Schiff base (ie, a compound with a functional group that contains a carbon-nitrogen double bond with the nitrogen atom connected to an aryl or alkyl group) with various drugs, including isoniazid, hydralazine, cycloserine, and penicillamine. In the case of isoniazid specifically, an isonicotyl hydrazine of pyridoxal is formed and excreted. Thus, formation of such complexes reduces the availability of the biologically active form of vitamin B6. Hence, all of these drugs are associated with vitamin B6-responsive neurotoxicity (but note that coadministration of isoniazid and pyridoxine does not interfere with the antituberculous activity of isoniazid).

Isoniazid can also differentially affect decarboxylation of L-Dopa and 5HTP and the formation of serotonin seems to be much more sensitive to isoniazid-induced pyridoxal phosphate deficiency than the formation of dopamine. Consequently, serotonin-deficiency phenomena (eg, behavioral disorders, sleep problems, etc.) but not dopamine-deficiency phenomena (eg, parkinsonism) have been reported with isoniazid toxicity (31).

Isoniazid toxicity (mediated by impaired pyridoxine metabolism) has a variety of neurologic consequences. Specifically, acute isoniazid toxicity produces seizures (82) and encephalopathy, obtundation, and coma (82) whereas chronic toxicity may be associated with peripheral neuropathy, optic neuropathy, and rarely with pellagra (154; 34; 50; 102) or coma (32; 213). Other reported neurologic manifestations include hyperkinesias and ataxia. Other nonneurologic manifestations include liver dysfunction (toxic hepatitis) and a sideroblastic anemia (199; 155; 222; 63).

In adults, acute ingestion of as little as 1.5 g of isoniazid can produce toxicity. Doses larger than 30 mg/kg often produce seizures whereas doses of 80 mg/kg or more can be rapidly fatal (204). The first signs and symptoms of isoniazid toxicity usually appear 30 minutes to 2 hours after ingestion (204). Symptoms and signs of isoniazid overdose include nausea, vomiting, ataxia, confusion, irritability, agitation, sleep disturbances, lethargy, coma, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and severe metabolic acidosis (with a high anion gap) (10). Pyridoxine administered intravenously is the only effective antidote and can effectively treat both the seizures and the alternations in arousal and mentation. The seizures are otherwise poorly responsive to standard anticonvulsant therapy. Although small doses of pyridoxine (or moderate to large doses of parenteral benzodiazepines) may be sufficient to stop the seizures associated with isoniazid overdose or toxicity, large doses of pyridoxine may be required to completely reverse the full spectrum of signs and symptoms, including the altered level of arousal. In any case, it is generally recommended to combine the use of pyridoxine and benzodiazepines (eg, diazepam) because in animal models the combination has a synergistic effect in terminating seizures associated with pyridoxine deficiency states (226; 185; 166). The initial dose of pyridoxine should be equal to the estimated amount of isoniazid ingested (226; 261; 273; 204; 247; 251; 166). Unfortunately, intravenous pyridoxine is typically stocked in limited quantities in hospitals, and many providers are unfamiliar with isoniazid toxicity, which can confound effective treatment of cases of isoniazid overdose or toxicity (221; 216; 171). Hemodialysis is an important adjunct to pyridoxine therapy in those with persistent coma or refractory seizures or in case of renal failure (225; 183; 36; 247; 245).

Children (and less commonly adults) can present with status epilepticus and the associated metabolic acidosis and coma can be mistakenly attributed solely to the prolonged seizures (162; 33; 228; 10; 231; 44; 150; 35; 166). Therefore, isoniazid toxicity should be considered in patients with refractory seizures (78), obtundation or coma (32; 262; 47; 246), and metabolic acidosis (10).

Risk factors for unintentional overdose or toxicity from isoniazid include children of patients taking isoniazid (including newborn infants of mothers taking isoniazid), uremia/dialysis, higher doses of isoniazid, and lack of concomitant pyridoxine prophylaxis (156; 187; 15; 39; 166). Patients on dialysis are particularly sensitive to isoniazid neurotoxicity in part because pyridoxal phosphate is rapidly cleared by dialysis, which compounds the toxicity of isoniazid (228). Consequently, hemodialysis patients requiring isoniazid therapy should receive supplemental pyridoxine at a dose of 100 mg/day (rather than the usual amount of 50 mg/day) (228). Overdose in adults can occur as a suicide attempt or when individuals attempt to make up missed doses at one time (227; 26; 82; 180; 244; 242; 120). In children, acute isoniazid toxicity should be suspected in those presenting with new-onset seizures (with or without a fever), particularly in those with known access to isoniazid (221).

Peripheral neuropathy is generally a rare complication of isoniazid when small doses are used. However, in malnourished individuals, the risk is apparently significantly greater (64). Neuropathy develops particularly in slow inactivators of isoniazid and can be prevented by concomitant administration of pyridoxine 6 mg daily (277; 128). Although risk can be minimized with concomitant pyridoxine administration, this is often not feasible for use in poorly developed countries; in such situations, vitamin B complex is often more practical (64). In addition, pyridoxine itself can cause a sensory peripheral neuropathy (179), though usually with high doses, and generally reversible with discontinuation of pyridoxine supplementation (although in severe cases there may be marked loss of large myelinated fibers) (215).

Optic neuropathy is a relatively rare side effect of isoniazid but when it occurs, it can be ameliorated by withdrawal of isoniazid and treatment with pyridoxine and possibly also corticosteroids (119; 116; 115; 76; 108; 84; 125; 124; 181; 132).

Isoniazid may precipitate pellagra (154; 50; 102), sometimes even despite pyridoxine supplementation (59). Withdrawal of isoniazid and supplementation with niacin can result in rapid clinical improvement. Isoniazid is metabolized by arylamine N-acetyltransferase and individuals with a less active form of this enzyme do not break down isoniazid efficiently and are more susceptible to pellagra.

Antiepileptic drugs. Treatment with enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (antiepileptic drugs such as phenytoin or carbamazepine) compared to noninducing antiepileptic drugs (eg, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, or topiramate) commonly causes pyridoxine deficiency, which may be severe (167). This may contribute to the polyneuropathy sometimes attributed to older antiepileptic drugs.

Carbidopa. Levodopa is decarboxylated to dopamine by DOPA decarboxylase, which requires PLP as a cofactor. To inhibit peripheral metabolism of L-DOPA (outside the brain) and the associated adverse symptoms (eg, nausea/vomiting, dizziness, headache, and somnolence), and to ensure a greater proportion of the prodrug is delivered to the brain, L-DOPA is usually combined with carbidopa, which inhibits aromatic-L-amino-acid decarboxylase (or "DOPA decarboxylase"). Carbidopa is a hydrazine derivative that binds covalently to PLP, blocking L-DOPA decarboxylation. Because the carbidopa-PLP bond is irreversible, chronic treatment with carbidopa produces systemic vitamin B6 depletion, particularly in subjects treated with high doses of carbidopa (202; 268). Carbidopa-induced pyridoxine deficiency can be symptomatic, particularly with anemia (274), and probably with neuropathy, but also (albeit uncommonly) with refractory seizures (268).

A decrease in PLP leads to a decrease in the irreversible conversion (decarboxylation) of L-glutamic acid to the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA by the PLP-dependent enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). In mammals, GAD exists in two isoforms with molecular weights of 67 and 65 kDa (GAD67 and GAD65), which are encoded by different genes on different chromosomes (GAD1 on chromosome 2 and GAD2 on chromosome 10). GAD67 and GAD65 are both expressed in the brain where GABA is used as a neurotransmitter. The GAD active site involves a Schiff base linkage between PLP and Lys405.

Carbidopa-induced pyridoxine deficiency may also help explain the high frequency of neuropathy in patients with Parkinson disease (203; 72), especially in patients treated with levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel infusion (111; 159; 189).

In a cross-sectional retrospective study of vitamin B6 plasma levels in 24 patients with Parkinson disease treated with L-DOPA/carbidopa for 3 or more years, all six patients treated with intraduodenal L-DOPA/carbidopa and 13 of 18 patients orally treated with L-DOPA/carbidopa had low plasma levels of vitamin B6; two thirds of the intraduodenal group had pyridoxine levels below the limit of quantification (202). Moreover, eight (42%) of the 19 patients with low vitamin B6 levels had symptoms of hypovitaminosis B6 (anemia and stomatitis/glossitis).

Carboplatin. Carboplatin forms complexes with pyridoxine (243), which can interfere with the action of carboplatin as an antitumor agent and can also produce symptomatic pyridoxine deficiency with neuropathy and depression (217).

Scheme of complexes of the Pt(NH3)2(OH)+ moiety of carboplatin with the B vitamins, including vitamin B6 (pyridoxine, or its active form pyridoxal 5'-phosphate). The only vitamin with a positive charge is thiamine (vitamin B1)....

The physico-chemical characterization of the interaction of these chemicals was performed using UV-vis (ultraviolet-visible) spectroscopic techniques in the wavelength range from 190 to 500 nm. UV-vis spectrophotometers use a l...

Inherited disorders of pyridoxine metabolism. There are several different genetic mechanisms that lead to an increased requirement for pyridoxine or pyridoxal phosphate. These include inborn errors that lead to accumulation of small molecules that react with pyridoxal phosphate and inactivate it, inborn errors affecting the pathways of pyridoxine metabolism, and inborn errors affecting specific pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzymes.

Inherited pyridoxine-responsive (or pyridoxal 5'-phosphate-responsive) conditions include the following (95):

(1) Autosomal-recessive pyridoxine-dependent neonatal epilepsy (OMIM #266100) is caused by deficiency or dysfunction of the enzyme antiquitin or ATQ1 (also known as α-amino-adipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase; and aldehyde dehydrogenase 7 family, member A1 or ALDH7A1), a key enzyme in lysine oxidation (164; 237; 55; 114).

EEG showed hypsarrhythmia during frequent cluster seizures in a patient with pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy caused by an ALDH7A1 mutation. The EEG was obtained at the age of 2 years before pyridoxine was used. (Source: ...

Despite adequate seizure control by early high-dose pyridoxine treatment, most patients (at least 75%) with pyridoxine-dependent neonatal epilepsy due to deficiency of α-aminoadipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH7A1) have developmental delay and intellectual disability (55; 272). Neuroimaging shows progressive severe cerebral atrophy, with a frontotemporal predominance.

ALDH7A1-deficient mice with seizure control exhibit altered adult hippocampal neurogenesis and impaired cognitive functions (272). ALDH7A1 deficiency leads to the accumulation of toxic lysine catabolism intermediates (eg, alpha-aminoadipic-delta-semialdehyde and its cyclic form, delta-1-piperideine-6-carboxylate), which impair de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis and inhibit neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation (272). In ALDH7A1-deficient adult mice, supplementation of pyrimidines rescues abnormal neurogenesis and cognitive impairment.

To improve outcome, a lysine-restricted diet and competitive inhibition of lysine transport using pharmacologic doses of arginine are recommended as an adjunct therapy (55).

(2) Pyridox(am)ine 5'-phosphate oxidase (PNPO) deficiency (OMIM #610090) (70; 79; 81).

(3) Pyridoxal phosphate-binding protein deficiency due to biallelic mutations in the PLPBP gene (OMIM *604436) on chromosome 8p11.23

(4) Some X-linked and autosomal-recessive forms of pyridoxine-responsive sideroblastic anemia (OMIM #300751 and 206000)

(5) Some milder autosomal-recessive cases of pyridoxine-responsive homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency (OMIM #236200)

(6) Autosomal recessive infantile hypophosphatasia (HPP; OMIM #241500) due to homozygous, compound heterozygous, or heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in the ALPL gene (OMIM #171760) on chromosome 1p36.12, resulting in deficient activity of serum tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP) (224). In all types of hypophosphatasia, abnormal mineralization of bone leads to rickets/osteomalacia and pathological fractures (92). Low TNSALP isoenzyme activity results in extracellular accumulation of its substrates, including pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi), a potent inhibitor of mineralization (122); however, concomitant B6 deficiency can negate the utility of elevated PLP levels for diagnosis (266). Clinical phenotypes of perinatal HPP include skeletal dysplasia, shorter long bones, bowing of long bones, tetraphocomelia, abnormal posturing, abnormal bone ossification, and a restricted dental abnormality with severe dental caries (276). Patients with perinatal or infantile hypophosphatasia and vitamin B6–dependent seizures have high morbidity and mortality in the first 5 years of life (265). B6-dependent seizures in infants with HPP have been attributed to profound deficiency of TNSALP activity, which blocks PLP dephosphorylation to pyridoxal and consequently diminishes GABA synthesis in the brain, but altered B6 metabolism may cause additional clinical complications as well (267). A human recombinant enzyme replacement therapy (asfotase alfa; initially named ENB-0040) has been developed to treat hypophosphatasia, and initial studies have suggested that in adults and adolescents with pediatric-onset hypophosphatasia, treatment is associated with normalization of circulating TNSALP substrate levels and improved functional abilities (264; 122; 121).

(7) Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor synthesis defects, including some cases of hyperphosphatasia with mental retardation syndrome 1 (Mabry syndrome; glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis defect 2) (OMIM #239300) (249; 130), and glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis defect 18 (OMIM #618143)

(8) Hyperprolinemia type II (OMIM #239510), a rare autosomal recessive disorder of proline metabolism caused by defective delta-pyrroline 5-carboxylate (P5C) dehydrogenase due to mutations in the ALDH4A1 gene (224; 172).

(9) Hyper-beta-alaninemia associated with Cohen syndrome, an autosomal recessive multisystem disorder characterized by facial dysmorphism, microcephaly, intellectual disability, truncal obesity, progressive retinopathy, and intermittent congenital neutropenia (OMIM #216550) (96).

Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy. Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy (OMIM #266100), a neonatal-onset epileptic encephalopathy, is characterized typically by neonatal-onset epileptic encephalopathy responsive to pharmacological doses of vitamin B6 but are resistant to standard antiepileptic drugs. Vitamin B6–dependent epilepsies result from various gene defects (involving the genes ALDH7A1, PNPO, ALPL, ALDH4A1, PLPBP as well as defects of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor proteins) that lead to reduced availability of pyridoxal 5'-phosphate, an important cofactor in neurotransmitter and amino acid metabolism (190).

Although seizures are a defining feature of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy, other disease manifestations (eg, developmental delay and intellectual disability) can vary widely even among affected siblings with early pyridoxine treatment (08; 49). Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy is associated with neuronal migration abnormalities and other structural brain defects, which persist despite postnatal pyridoxine supplementation and likely contribute to neurodevelopmental impairments (105).

Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy results from an inherited metabolic defect that is transmitted as an autosomal-recessive trait. Deficiency or dysfunction of the enzyme antiquitin or ATQ1 (also known as α-amino-adipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase; and aldehyde dehydrogenase 7 family, member A1 or ALDH7A1), encoded by the ALDH7A1 gene on chromosome 5q23.2, has been identified as the underlying cause of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy in most cases (164; 21; 49). This enzyme functions in a critical step in the lysine degradation pathway in the human brain.

In the saccharopine pathway of lysine degradation in the human brain, lysine is converted first to saccharopine by lysine-α-ketoglutarate reductase and then to α-aminoadipic semialdehyde (α-AASA) by α-aminoadipic semialdehyde synthase (AASS); AASA is subsequently converted to α-aminoadipate (AAA) by antiquitin (165; 237; Hallen and Jamie 2013; 54). Antiquitin dysfunction causes an accumulation of the open-chain aldehyde α-AASA and its cyclic form δ1-piperidine-6-carboxylic acid (P6C), which serve as diagnostic markers in urine and plasma (192; 237). P6C binds and inactivates the active form of pyridoxine (ie, pyridoxal 5'-phosphate or PLP) by forming a Knoevenagel condensation product that no longer has the PLP aldehyde group essential for its function as a cofactor (165; 237; 240). In the absence of the functioning coenzyme pyridoxal phosphate, glutamic acid decarboxylase is unable to decarboxylate glutamic acid to GABA, causing depletion of GABA and the resultant clinical manifestations of seizures. Administration of pyridoxine arrests seizures and may also foster normal development. In addition, rare but treatable causes of unexplained epilepsy extending beyond the classical phenotypes may also result from atypical presentations of ALDH7A1 gene mutations (21; 250).

Folinic acid-responsive seizures are also often due to alpha-AASA dehydrogenase deficiency resulting from mutations in the ALDH7A1 gene, and consequently overlap with the major form of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy (74; 209; 85; 237), though some have mutations in the folate receptor 1 (FOLR1) gene (65; 05) or the syntaxin binding protein 1 (STXBP1) gene (253).

Other cases of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy result from mutations in different genes (112), including mutations in the molybdenum cofactor synthesis 2 (MOCS2) gene and the potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 2 (KCNQ2) gene (240; 12; 190). Two cases of KCNQ2-related neonatal epilepsies [a 5-year-old male with a paternally inherited heterozygous mutation (c.1639C> T; p.Arg547Trp) and a 10-year-old female with a de novo heterozygous mutation (c.740C> T; p.Ser247Leu)] benefited from pyridoxine treatment; several potential mechanisms have been proposed (12). Urinary excretion of α-AASA is also increased in molybdenum cofactor and sulfite oxidase deficiencies resulting from mutations in the molybdenum cofactor synthesis 2 (MOCS2) gene (240).

Several etiopathogenic mechanisms have been proposed to explain the responsiveness of some neonatal seizures to pyridoxine, and particularly to its active form, pyridoxal 5′ phosphate (PLP). PLP acts as a cofactor of several en...

Pyridoxamine 5'-phosphate oxidase deficiency. Pyridoxamine 5'-phosphate oxidase deficiency (PNPOD; OMIM #610090) is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the PNPO gene (OMIM #603287) on chromosome 17q21. Human PNPO has an allosteric pyridoxal 5'-phosphate binding site that plays a crucial role in regulation of the enzyme and consequently in the regulation of vitamin B6 metabolism (20). This condition has also been called PNPO-related neonatal epileptic encephalopathy. To date only about 20 cases have been reported (165; 219; 191; 260). Deficiency of pyridox(am)ine 5’-phosphate oxidase impairs pyridoxal 5’-phosphate synthesis and recycling.

Pyridoxamine 5'-phosphate oxidase deficiency is an autosomal-recessive inborn error of metabolism resulting in vitamin B6 deficiency that manifests with severe neonatal-onset seizures and subsequent encephalopathy (219). Affected individuals are often born premature with fetal distress (ie, low Apgar scores or requiring intubation) to consanguineous parents (165). Patients typically present in the neonatal period with recurrent myoclonic and clonic contractions, tonic jerks, or hemiclonic seizures, accompanied by rolling or rotary eye movements and oxygen desaturation. Seizures typically begin on the first day of life and in the absence of treatment often rapidly progress to status epilepticus. Patients carrying the missense mutation c(674G> A) p(R225 H) of the PNPO gene may have a more severe epileptic phenotype because of their lower residual PNPO activity (145). In addition, some cases reported a faltering or high-pitched cry, hypersalivation, rhythmic orobuccal movements, encephalopathy, and hypertonia. EEG showed burst-suppression patterns or discontinuous tracings (191), though one patient was reported with centrotemporal spikes with rare generalized spike-wave bursts (260).

A wider clinical spectrum has been recognized, with some having recognized onset as late as 5 months (107). Nevertheless, only about 40% were seizure-free with pyridoxine or pyridoxal-5'-phosphate treatment. Two cases had positive results to anticonvulsant therapy for 17 months and more than 8 years. Surviving cases generally have severe neurocognitive delay, but better results are seen in those who respond to pyridoxine.

Biochemical analysis of cerebrospinal fluid and urine suggested aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency, though frequently with additional features of raised glycine, threonine, taurine, and histidine, and low arginine; genetic defects in the AADC gene (OMIM #107930) were excluded in these cases. Laboratory studies also show hypoglycemia, acidosis, anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathy. Serial brain imaging shows progressive hypomyelination and global atrophy.

Patients with pyridoxamine 5'-phosphate oxidase (PNPO) mutations may respond better to treatment with pyridoxal 5'-phosphate than to pyridoxine (191). Seizures typically respond completely or partially to pyridoxine treatment and often dramatically to pyridoxal phosphate. Breakthrough seizures while on pyridoxine develop in more than half of the patients (191). Status epilepticus may occur following replacement of pyridoxine with pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (191). Consequently, some authors have employed initial combination therapy with both pyridoxine and pyridoxal 5'-phosphate followed by gradual taper of pyridoxine (260).

Affected individuals generally had poor clinical outcomes with global developmental delay, autism spectrum disorder, severe neurologic sequelae, and high mortality, particularly if treatment is delayed.

Prenatal diagnosis of pyridoxamine 5'-phosphate oxidase deficiency using chorionic villus sampling after a sibling had been previously diagnosed postnatally (165).

PLP homeostasis protein (PLPHP) deficiency. Biallelic mutations in the PLPBP gene (OMIM *604436) on chromosome 8p11.23 are another cause of vitamin B6-dependent epilepsy (OMIM #617290) (58; 194; 106; 109; 09; 113). The gene product, PLP homeostasis binding protein PLPHP, a homolog of bacterial proline synthetase cotranscribed (PROSC), is likely to be present in both cytoplasm and mitochondria (109). PLPHP has a pyridoxal 5’-phosphate-binding domain but no enzymatic activity.

PLPHP deficiency in humans is manifested by early-onset intractable seizures responsive to pyridoxine or PLP, developmental delay, and structural brain abnormalities, most notably simplified gyral pattern and cyst-like structures adjacent to the anterior horns (58).

PLPHP acts in intracellular homeostatic regulation of pyridoxal 5’-phosphate, presumably as a carrier that prevents pyridoxal 5’-phosphate from reacting with other molecules (including protecting it from intracellular phosphatases) and that supplies it to apo-enzymes (58).

In addition to early-onset B6-dependent epilepsy, developmental delay and intellectual disability of variable severity are common but not universal (106; 09).

Some patients may have clusters of paroxysmal events resembling seizures that respond to vitamin B6 but without EEG correlates, raising the possibility of a B6-responsive movement disorder (09).

Hyperglycinemia and hyperlactatemia are the most consistently observed biochemical abnormalities (106).

Pyridoxine-responsive homocystinuria. Untreated homocystinuria usually manifests in the first or second decade of life with intellectual disability, myopia, ectopia lentis, skeletal anomalies (resembling Marfan syndrome), and thromboembolic events. Because pyridoxine is a cofactor for the cystathionine beta-synthase enzyme it facilitates the conversion of homocysteine to cysteine (201; 248). Some patients with autosomal recessive homocystinuria from cystathionine synthase deficiency may be treated effectively with high doses of vitamin B6 (173; 269).

Pyridoxine toxicity. In the 1980s multiple authors described sensory neuronopathy (and less commonly a sensorimotor neuropathy) in patients who consumed high doses of pyridoxine (218; 186; 07; 57; 06; 157; 77; 80; 131; 68). Some of these cases were iatrogenic, resulting from pyridoxine treatment of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy, homocystinuria, mushroom poisoning, and premenstrual syndrome (07; 57; 06; 157; 68). The pyridoxine dose varied from 200 mg to 10 g per day for periods of up to 20 years. Symptoms began 1 month to several years after starting pyridoxine. In a study of B6 levels in a well-characterized cohort of patients with chronic idiopathic axonal polyneuropathy, moderately elevated plasma B6 levels, even in the 100 to 200 μg/L range, were not associated with significantly worse neuropathy signs or symptoms (236). Duration of consumption prior to symptom onset was inversely proportional to dose. In many cases, symptoms partially improved following discontinuation of pyridoxine but many were still left with severe disability.

Animal models of pyridoxine toxicity have been developed in a variety of animals including dogs (127; 45; 43; 275), guinea pigs (271), cats (234), and rats (195). Additional models of acute auditory neuropathy have been studied after massive administrations of pyridoxine (97). Loss of large-size neurons in the dorsal root ganglia on dogs with experimental pyridoxine toxicity is potentially reversible (275) and recovery can be facilitated with beta-nerve growth factor (β-NGF) (43).

The relationship between pyridoxine overdose levels and histological damage has now been well characterized in both humans and animals. Pyridoxine given in large doses selectively destroys large-diameter peripheral sensory nerve fibers, leaving motor fibers intact.

The pathogenic mechanism of pyridoxine toxicity has not been well characterized, but one possibility is that high circulating concentrations of pyridoxine may inhibit pyridoxal kinase, which disrupts GABAergic transmission and results in excitotoxicity, neurodegeneration, and, ultimately, a sensory neuronopathy (90).

|

• Vitamin B6 deficiency is rare because most foods contain the vitamin. | |

|

• Robust quantities of pyridoxine can be found in meats, particularly liver, fish, and chicken; vegetables, such as beans, peas, and tomatoes; fruits, including oranges, bananas, and avocados; and grains, like enriched breads, cereals, and grains. | |

|

• Physiologic availability of pyridoxine depends on dietary supply, intact absorption, and conversion of pyridoxamine and pyridoxine into the active cofactor in the liver. | |

|

• Pregnant and lactating women have higher daily requirements of pyridoxine than the minimum daily requirement for other adults. |

Pyridoxine deficiency is often associated with concomitant deficiencies of other water-soluble vitamins (eg, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid, biotin, cobalamin, and folic acid) (133). Alarming levels of inadequate intake of B group vitamins, including pyridoxine, have been documented in tribal lactating women from South India (133).

Isolated dietary pyridoxine deficiency is very rare in the United States, in part because most foods contain the vitamin. Robust quantities can be found in meats, particularly liver, fish, and chicken; vegetables, such as beans, peas, and tomatoes; fruits, including oranges, bananas, and avocados; and grains, like enriched breads, cereals, and grains. Physiologic availability depends on dietary supply, intact absorption, and conversion of pyridoxamine and pyridoxine into the active cofactor (ie, pyridoxal 5'-phosphate) in liver (193). In addition, pyridoxine is produced by the gut microflora (211).

In developed countries, acquired pyridoxine deficiency is usually drug induced (eg, isoniazid, hydralazine, penicillamine, levodopa, and some chemotherapeutic drugs) in the absence of an inborn error of metabolism. Some drug-related causes of pyridoxine deficiency interfere with its metabolism (243; 217).

The minimum daily requirement of pyridoxine is approximately 1.5 mg; however, the recommended daily intake by the U.S. National Research Council is 2 mg for adults and 0.3 mg for infants. Pregnant women require an additional 0.1 mg per day, and women that are lactating require an additional 0.7 to 0.8 mg daily (223; 230). The most common supplemental intake is 10 to 25 mg per day; however, high amounts (100 to 200 mg per day or even more) may be recommended for certain conditions.

Low-plasma vitamin B6 levels, measured as pyridoxal 5'-phosphate, are associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (98).

Children with sickle cell disease have significant hyperhomocysteinemia associated with pyridoxine and relative folate deficiencies (19). However, pyridoxine supplementation in people with sickle cell anemia has not been shown to improve hematologic indexes or disease activity.

The estimated incidence of ALDH7A1 gene mutations resulting in pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy is 1 in 64,352 live births (52) whereas earlier studies provided much lower estimates from 1 in 276,000 (28) to between 1 in 400,000 and 1 in 700,000 (22).

In a population-based transnational Norwegian study, the estimated minimum prevalence of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy was 6.3 per million among children and 1.2 per million among adults (104).

|

• Prophylactic administration of pyridoxine should be provided when a patient is using certain medications, such as isoniazid and penicillamine. | |

|

• Pyridoxine supplementation of malnourished children treated for tuberculosis is advisable, particularly those who are HIV-infected. | |

|

• In critically ill patients, a large parenteral dose of vitamin B6 supplementation may compensate for the lack of responsiveness of plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate to oral vitamin B6 intake and also increase the immune response of such patients. | |

|

• In the absence of a compelling medical indication and a specific prescription by a knowledgeable medical provider, patients should be discouraged from using doses of vitamins exceeding package recommendations and particularly from using over-the-counter formulations of vitamin B6. |

Prophylactic administration of pyridoxine should be provided when a patient is using certain medications, such as isoniazid (30 to 450 mg/d, which may be based gram for gram) (207; 254; 229; 153; 258; 142; 46; 255) and penicillamine (100 mg/d). Pyridoxine supplementation of malnourished children treated for tuberculosis is advisable, particularly those who are HIV-infected (46).

In critically ill patients, a large parenteral dose of vitamin B6 supplementation (50 or 100 mg/day for 14 days) may compensate for the lack of responsiveness of plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate to oral vitamin B6 intake and may increase the immune response of such patients (38).

In a study of nursing home residents, almost 50% of residents were deficient in vitamin B6 (123). Vitamin supplements were recommended as an effective prophylaxis for deficiency in all elderly people in nursing homes.

Other rare medical conditions, such as cystathionase deficiency, can be treated with large doses of pyridoxine even though they are not due to a pyridoxine deficiency (142).

It is important to recognize an X-linked hereditary sideroblastic anemia early in life as a significant percentage of cases respond to pyridoxine, thus, avoiding long-term complications (88). Plasma vitamin B6 levels should be ordered as a part of the workup of any unexplained anemia before labeling it as "anemia of chronic disease" (198).

When vitamin B6 is administered daily in supraphysiologic doses, neurotoxicity may occur (typically at levels > 100 nmol/L or 25 μg/L) (198). The frequency of overdosage with vitamin B6 has increased in recent years due to an increase in B6 supplementation overuse (29). In the absence of a compelling medical indication and a specific prescription by a knowledgeable medical provider, patients should be discouraged from using doses of vitamins exceeding package recommendations and particularly from using over-the-counter formulations of vitamin B6. When supplementation is deemed necessary, PLP-based supplements are preferred over pyridoxine supplements because PLP has minimal neurotoxicity in neuronal cell viability tests (198). Weekly administration is preferred over daily use because vitamin B6 metabolites have a long half-life.

Genetically determined neonatal epileptic encephalopathies most commonly result from mutations in the ALDH7A1 gene on chromosome 5q23.2 or the PNPO gene on chromosome 17q21 but may also result from mutations in other genes, including the folate receptor 1 (FOLR1), syntaxin binding protein 1 (STXBP1), and molybdenum cofactor synthesis 2 (MOCS2) genes. Patients with pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy due to mutations in the ALDH7A1 gene generally respond dramatically to pyridoxine, whereas some patients with PNPO deficiency respond better to pyridoxal phosphate. In patients with PNPO deficiency, biochemical analysis of cerebrospinal fluid and urine may suggest aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Clinically genetically determined neonatal epileptic encephalopathies may resemble hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

Confusion with other inborn errors of metabolism (eg, mitochondrial encephalopathy, glycine encephalopathy) has produced harmful delays in initiating vitamin B6 in patients with PLPBP deficiency (106; 109).

Viral infections, paraneoplastic conditions (paraneoplastic subacute sensory neuronopathy), dysimmune disorders (Sjögren syndrome, Miller Fisher syndrome, and Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis), some toxins, and some medications (eg, cisplatin toxicity) can rarely produce a sensory ataxic neuropathy (235; 56; 134).

Peripheral neuropathy from pyridoxine deficiency may resemble other nutritional and metabolic sensorimotor axonal neuropathies.

|

• Pyridoxine deficiency can be diagnosed by checking plasma and erythrocyte pyridoxal 5'-phosphate concentrations. | |

|

• EMG studies of patients with pyridoxine deficiency can demonstrate absent or severely reduced sensory nerve action potentials with mild slowing of sensory nerve conduction velocities; compound motor action potential and motor nerve conduction velocity are normal. | |

|

• Sural nerve biopsy of patients with pyridoxine deficiency shows axonal degeneration of both large- and small-diameter myelinated fibers. | |

|

• Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy or PNPO should be considered in infants with prolonged episodes of mixed, multifocal, myoclonic, or tonic symptoms, particularly when associated with grimacing and abnormal eye movements. | |

|

• In children with neonatal- or early-infantile-onset seizures, pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy can be confirmed by elevated urinary, plasma, or cerebrospinal fluid alpha aminoadipic-6-semialdehyde (α-AASA) levels and genetic testing for ALDH7A1 mutations. | |

|

• Confusion with other inborn errors of metabolism has produced delays in initiating vitamin B6 in patients with PLPBP deficiency. | |

|

• EEG findings in neonates and infants with pyridoxine-dependent seizures are characterized by repetitive runs of high-voltage, generalized, bilateral, synchronous 1 to 4 Hz spikes, and sharp wave bursts. | |

|

• Normalizing EEG findings or causing clinical cessation of seizures by injecting 100 mg of intravenous pyridoxine identifies pyridoxine-dependent and pyridoxine-responsive seizures. | |

|

• Vitamin B6 toxicity does not require laboratory or other tests. |

Pyridoxine deficiency. Pyridoxine deficiency can be diagnosed by checking plasma and erythrocyte pyridoxal 5'-phosphate concentrations. The reference range for pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), the biologically active form of vitamin B6, is 550 µg/L.

Other biochemical and metabolic tests are employed in research studies to assess pyridoxine status but are not generally needed in clinical practice. These include the erythrocyte aspartate aminotransferase activity coefficient (a long-term indicator of functional pyridoxine status), net homocysteine increase in response to a methionine load test, 24-hour urinary xanthurenic acid excretion in response to a tryptophan load test, and urinary 4-pyridoxic acid levels (to examine the impact of pyridoxine treatment on vitamin B6 excretion) (40).

Hematologic indexes may indicate the presence of a hypochromic-microcytic anemia with normal iron levels. Patients with inherited sideroblastic anemias have marked red blood cell dimorphism, anisocytosis, and poikilocytosis.

EMG studies of patients with pyridoxine deficiency can demonstrate absent or severely reduced sensory nerve action potentials with mild slowing of sensory nerve conduction velocities. Compound motor action potential and motor nerve conduction velocity are normal.

Sural nerve biopsy of patients with pyridoxine deficiency shows axonal degeneration of both large- and small-diameter myelinated fibers. Clinical neurophysiologic testing like EMG or EEG can be obtained based on the underlying symptoms. Some patients may develop small fiber neuropathy and dysautonomia and autonomic testing may be helpful in selected cases (17).

Neonatal epileptic encephalopathy. Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy or PNPO should be considered in infants with prolonged episodes of mixed, multifocal, myoclonic, or tonic symptoms, particularly when associated with grimacing and abnormal eye movements (219).

In neonates with therapy-resistant seizures, a diagnostic trial with pyridoxine, 30 mg/kg per day in two single dosages over 3 consecutive days, is recommended (67). If ineffective, a trial of pyridoxal 5ʹ-phosphate, 30 to 50 mg/kg per day in four to six single dosages, can be considered at the discretion of the treating physician.

Biomarkers for several genetic disorders associated with vitamin B6-dependent epilepsies (ALDH7A1 deficiency, PNPO deficiency, ALPL deficiency causing congenital hypophosphatasia, ALDH4A1 deficiency, and glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchoring defects with hyperphosphatasia) can be detected in plasma or urine, whereas there is no biomarker to test for PLPHP deficiency (Table 1) (190).

|

Disorder |

Gene |

Urine |

Plasma |

CSF |

|

Antiquitin deficiency |

ALDH7A1 |

Increased AASA, P6C, PA*; Inconsistently elevated vanillactate |

Increased PA, 2-OPP* |

Increased AASA, P6C; Deceased PLP; Secondary NT abnormalities |

|

PNPO deficiency |

PNPO |

Inconsistently elevated vanillactate |

Increased pyridoxamine |

Deceased PLP; Secondary NT abnormalities |

|

Congenital hypophosphatasia |

ALPL |

Decreased AP; Increased Ca and Ph | ||

|

PLPHP deficiency |

PLPBP | |||

|

Hyperprolinemia type 2 |

ALDH4A1 |

Increased P5C |

Increased proline | |

|

Abbreviations: 2-OPP: 2S,6S-/2S,6R-oxopropylpiperidine-2-carboxylic acid; AASA: alpha-aminoadipic semialdehyde; AP: alkaline phosphatase; Ca: calcium; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; NT: neurotransmitters; P5C: L-delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate; P6C: L-delta1-piperidine-6-carboxylate; PA: pipecolic acid; Ph: phosphorus; PLP: pyridoxal 50-phosphate * So far only detected by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS) metabolome analysis | ||||

|

Adapted from: (89; 190) | ||||

In children with neonatal- or early-infantile-onset seizures, pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy can be confirmed by elevated urinary, plasma, or cerebrospinal fluid alpha aminoadipic-6-semialdehyde (α-AASA) levels and genetic testing for ALDH7A1 mutations. Low cerebrospinal fluid pyridoxal concentrations may be better than low cerebrospinal fluid pyridoxal 5'-phosphate concentrations as an indicator of pyridoxal 5'-phosphate deficiency in the brain in vitamin B6-dependent epilepsy (03). Urinary screening for α-AASA accumulation is a reliable tool to diagnose pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy and should be included in the evaluation of patients with neonatal epileptic encephalopathy, as well as those with later-onset seizures (28; 192; 74; 182). α-AASA is in spontaneous equilibrium with its cyclic form δ1-piperideine-6-carboxylate (P6C), a molecule with a heterocyclic ring structure (241); the diagnostic utility of assessments of urinary P6C is comparable to that of α-AASA (241).

Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the ALDH7A1 gene have been identified in most patients with pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy (165; 214; 103). ALDH7A1 gene analysis also provides a means for prenatal diagnosis of this condition (165). Structural brain malformations can occur with pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy and should not preclude evaluation for genetic causes (103).

Confusion with other inborn errors of metabolism has produced delays in initiating vitamin B6 in patients with PLPBP deficiency (106; 109): two cases were initially misdiagnosed as mitochondrial encephalopathy because of persistent lactic acidemia and overlapping clinical, neuroradiological, and laboratory features (ie, persistent lactic acidemia) and another case was initially misdiagnosed as glycine encephalopathy because of glycine elevation in plasma (106). Neither of the cases misdiagnosed as mitochondrial encephalopathy had a vitamin B6 trial and both ended fatally. In the case misdiagnosed as glycine encephalopathy, vitamin B6 treatment was not considered and instead the patient was treated unhelpfully with sodium benzoate and dextromethorphan (106). Because a metabolic biomarker for early detection of PLPBP deficiency is still lacking (106), and as the clinical and metabolic presentation is not specific, diagnostic confirmation depends on assessing response to an early vitamin B6 treatment trial in patients with early epileptic encephalopathy and on genetic testing (106).

In neonates with unexplained early onset intractable seizures, lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid metabolite analysis can be helpful in the differential diagnosis of inborn errors of metabolism that lead to infantile epilepsy (252; 101).

EEG findings in neonates and infants with pyridoxine-dependent seizures are characterized by repetitive runs of high-voltage, generalized, bilateral, synchronous 1 to 4 Hz spikes and sharp wave bursts. Normalizing EEG findings or causing clinical cessation of seizures by injecting 100 mg of intravenous pyridoxine identifies pyridoxine-dependent and pyridoxine-responsive seizures.

Pyridoxine toxicity. Vitamin B6 toxicity does not require laboratory or other tests.

|

• Although the minimum daily requirement of pyridoxine is only approximately 2 mg in adults, 50 mg/d or more may be required for successful therapy in the deficiency states. | |

|

• One needs to be cautious as supplemental therapy with doses greater than 50 mg/d for a prolonged duration may be harmful. | |

|

• Given that permanent disabling sensory ataxia may develop with pyridoxine administration, sometimes even with modest doses, it is prudent to avoid prescribing (or using) this medication as symptomatic therapy without a clear and compelling indication, especially when potential marginal benefits do not outweigh the serious risks of permanent harm. | |

|

• A trial of pyridoxine is recommended in all patients with the onset of seizures before 18 months of age, regardless of type. | |

|

• There is currently no specific antidote for the treatment of pyridoxine intoxication: neither emesis, lavage, nor administration of activated charcoal changed the ultimate outcome of pyridoxine-poisoned patients. Therefore, it remains essential to recognize the signs of toxicity and use pyridoxine only for essential indications with appropriate dosing. |

The goals of pharmacotherapy are to reduce morbidity and to prevent complications. Although the minimum daily requirement of pyridoxine is only approximately 2 mg in adults, 50 mg/d or more may be required for successful therapy in the deficiency states. However, one needs to be cautious as supplemental therapy with doses greater than 50 mg/d for a prolonged duration may be harmful.

Pyridoxine supplementation has been previously advocated for use by bodybuilders and for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome (135), carpal tunnel syndrome (16), tardive dyskinesia (141), childhood autism, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, all with at best variable results.

Given that permanent disabling sensory ataxia may develop with pyridoxine administration, sometimes even with modest doses, it is prudent to avoid prescribing (or using) this medication as symptomatic therapy without a clear and compelling indication, especially when potential marginal benefits do not outweigh the serious risks of permanent harm.

Neonatal epileptic encephalopathy. A trial of pyridoxine is recommended in all patients with the onset of seizures before 18 months of age, regardless of type (86; 106). Seizures typically cease within an hour of the administration of 50 to 100 mg of pyridoxine and remain controlled by 5 to 10 mg/kg per day of pyridoxine. Lifelong therapy is required (85). Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate may benefit patients at risk for pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy who do not respond to pyridoxine (219; 94). Because occasional patients with later diagnosis by molecular studies may fail short-term trials of pyridoxine, a prolonged course of pyridoxine therapy is justified, regardless of the initial therapeutic response, to identify delayed responders in infants with drug-refractory epilepsy of no apparent etiology (42).

Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy, pyridoxamine 5’-phosphate oxidase deficiency, and pyridoxal phosphate-binding protein deficiency are rare diseases that necessitate rapid diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Because the results of genetic and biochemical diagnostic tests are not available for at least several hours, immediate administration of pyridoxine and pyridoxal 5’-phosphate is recommended to make a preliminary diagnosis (219; 106). However, pyridoxal 5’-phosphate is not licensed in many countries and often not readily available in hospitals (219; 238). PLP food supplements are regulated less stringently than medication and may prove to be of insufficient effectiveness and safety (238).

Treatment with folinic acid should be considered in neonatal seizures of unknown origin that do not respond to pyridoxine or manifest only a transient response to pyridoxine (252; 73; 178). Some have advocated treatment with both pyridoxine and folinic acid for patients with antiquitin (alpha-AASA dehydrogenase) deficiency (74).

Patients with confirmed antiquitin deficiency should have adjunct treatment with a lysine-restricted diet unless treatment with pyridoxine alone has resulted in complete symptom resolution, including normal behavior and development (74; 256; 151; 55). Lysine restriction should be started as early as possible, but the optimal duration of dietary restriction is undetermined (256). Long-term outcome can be improved if early therapy includes combination of pyridoxine/arginine supplementation and a lysine-restricted diet (149; 151).

|

Adult | ||

|

• Gyromitra poisoning: 25 mg/kg intravenously over 15 to 30 minutes, repeat when necessary (total dose 15 to 20 g/d) | ||

|

Pediatric | ||

|

• Pyridoxine-dependent seizures | ||

|

- Neonates with seizures: 50 to 100 mg intravenous or intramuscular as a single dose | ||

|

• Not established for cirrhosis, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and chronic renal failure | ||

Pyridoxine toxicity. There is currently no specific antidote for the treatment of pyridoxine intoxication (126; 142). Neither emesis, lavage, nor administration of activated charcoal changed the ultimate outcome of pyridoxine-poisoned patients. Therefore, it remains essential to recognize the signs of toxicity and use pyridoxine only for essential indications with appropriate dosing.

Pyridoxine has been advocated for hyperemesis gravidarum (on the basis of weak evidence) and may be more effective than placebo at reducing nausea, though its effect on vomiting is unclear (210; 259; 71; 158). Studies have most often assessed the effects of pyridoxine therapy in combination with doxylamine so the specific effects of pyridoxine if any are unclear. The combination therapy, which was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in April 2013 with a pregnancy safety rating of A, has been recommended as first-line pharmacologic treatment for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. However, a 2015 Cochrane Database systematic review concluded that: “there is not enough evidence to detect clinical benefits of vitamin B6 supplementation in pregnancy and/or labour other than one trial suggesting protection against dental decay” (212).

Pyridoxine had also been claimed to be an effective treatment for gestational diabetes, but this has been disproven (188; 83).

All contributors' financial relationships have been reviewed and mitigated to ensure that this and every other article is free from commercial bias.

Douglas J Lanska MD MS MSPH

Dr. Lanska of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and the Medical College of Wisconsin has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

See ProfileNearly 3,000 illustrations, including video clips of neurologic disorders.

Every article is reviewed by our esteemed Editorial Board for accuracy and currency.

Full spectrum of neurology in 1,200 comprehensive articles.

Listen to MedLink on the go with Audio versions of each article.

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

General Neurology

Jan. 13, 2025

General Neurology

Jan. 13, 2025

Neuro-Ophthalmology & Neuro-Otology

Jan. 08, 2025

Neuro-Ophthalmology & Neuro-Otology

Jan. 07, 2025

Peripheral Neuropathies

Dec. 30, 2024

General Neurology

Dec. 30, 2024

General Neurology

Dec. 13, 2024

General Neurology

Dec. 13, 2024