Epilepsy & Seizures

Tonic status epilepticus

Jan. 20, 2025

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Worddefinition

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas.

Reflex epileptic seizures are seizures that are elicited by specific extrinsic (light, tactile, acoustic), intrinsic (thinking, reading, emotional), or combined stimuli. They affect patients of all ages and have a 4% to 7% prevalence among patients with epilepsies and up to 21% prevalence in those with idiopathic generalized epilepsies (118).

The specific precipitating stimulus and the clinical or EEG response determine reflex epileptic seizures. Seizures may be generalized (absences, myoclonic jerks, or generalized tonic-clonic seizures) or focal (visual, sensorimotor, or limbic). The electroclinical events may only be limited to the stimulus-related receptive brain region, spread to other cortical areas, or become generalized. Flickering lights are the commoner triggering stimuli, and this is particularly relevant to modern life, with ever-increasing numbers of television- and video game–induced seizures. The flickering lights in nightclubs and discotheques are particularly potent. The etiology is diverse, from just a mild genetically determined propensity for reflex seizures in otherwise normal people to severe forms of focal or generalized epilepsies. The role of EEG is fundamental in establishing the precipitating stimulus in reflex epilepsies because it allows subclinical EEG reflex abnormalities, or minor clinical ictal events, to be reproduced on demand by application of the appropriate stimulus. Identifying the offending stimuli has significant clinical implications in managing patients because some may not need anything other than avoiding or modifying the precipitating factors.

• Heterogeneous extrinsic and intrinsic stimuli provoke reflex seizures and affect 4% to 7% of all epilepsies. | |

• Visually induced seizures are the most common types of reflex seizures. | |

• Reflex seizures elicited by reading, thinking, music, eating, hot water, emotions, or movement are less common. | |

• Clinically, reflex seizures are focal or generalized (absences, myoclonic jerks, generalized tonic-clonic seizures). | |

• Patients may have reflex seizures alone or together with spontaneous ones. | |

• Certain epileptic syndromes (juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, Dravet syndrome, progressive myoclonic epilepsies) commonly manifest with reflex epileptic seizures. | |

• EEG's role is fundamental in identifying the offending stimuli, with significant clinical and pathophysiological implications. | |

• Avoidance or modification of the provocative stimulus is the key point of management, and this may be sufficient for patients with reflex seizures only. | |

• Appropriate antiepileptic medication is needed for those with continuing reflex and spontaneous seizures. |

Reflex seizures of different types have been known for centuries (08). Recognition of seizures induced by flashing light predates the invention of EEG and the stroboscope and reaches to classical antiquity (121; 81; 60).

The first reference to reflex epilepsy is attributed to Apuleius Lucius (150 AD), a Roman philosopher, in his Apologia and Florida. However, Apuleius does not refer to flickering lights.

Nay, even supposing I had thought it a great achievement to cast an epileptic into a fit, why should I use charms when, as I am told by writers on natural history, the burning of the stone named gagates is an equally sure and easy proof of the disease? For its scent is commonly used as a test of the soundness or infirmity of slaves even in the slave-market. Again, the spinning of a potter's wheel will easily infect a man suffering from this disease with its own giddiness. For the sight of its rotations weakens his already feeble mind, and the potter is far more effective than the magician for casting epileptics into convulsions. |

“Gagates” is an old name for the stone “jet” or “black amber,” a carbon fossil that is compact and very light. Jet was known in ancient Egypt, where it was used for making mirrors; in Greece and Rome, it was used for cutting amulets, bracelets, and rings. In Medieval times, jet was popular as a talisman and a medicine for migraines, toothache, stomach pains, and epilepsy, and it reached the height of its popularity during the Victorian period. Also, the potter’s wheel in that time was solid, not spoked, which would be needed to produce intermittent light.

The oldest clear reference to photosensitive epilepsy is by Soranus of Ephesus (2nd century AD), a Greek gynecologist, obstetrician, and pediatrician who wrote On Acute and Chronic Diseases, which contains an excellent chapter on nervous disorders.

The use of flame, or very bright light obtained from flame has an agitating effect. In fact when a case of epilepsy is in its quiescent stage, the ultimate use of light with its sharp penetrating action may cause the recurrence of an attack. |

Reflex epilepsy was first documented in animals by the Italian school of neurophysiologists in the 1920s and 1930s (175). In his pioneering studies of “epilepsy from afferent stimuli,” Amantea found that clonus induced by the application of a small disc of blotting paper soaked with strychnine to the sensorimotor cortex of dogs was enhanced by the stimulation of the peripheral area somatotopically related to excited cortex (03; 04). Moreover, when stimulation of the skin persisted, clonus progressed to a generalized tonic-clonic seizure in approximately 25% of animals. Later, strychninization of the visual cortex was used by Clementi, the first to describe experimental light-induced epilepsy in studies of photic stimulation in dogs after strychnine application to the visual cortex (20).

The first medical evidence of photosensitive epilepsy by Gowers (58), and later by Holmes (69), refers to occipital seizures induced by light.

In very rare instances the influence of light seems to excite a fit. I have met with two examples of this. One was a girl of seventeen whose first attack occurred on going into bright sunshine for the first time, after an attack of typhoid fever. The immediate warning of an attack was giddiness and rotation to the left. At any time an attack could be produced by going out suddenly into bright sunshine. If there was no sunshine an attack did not occur. The other case was that of a man, the warning of whose fits was the appearance before the eyes of “bright blue lights, like stars — always the same”. The warning, and a fit, could be brought on at any time by looking at a bright light, even a bright fire. The relation is, in this case, intelligible, since the discharge apparently commenced in the visual centre (58). Some men subject to epileptiform attacks commencing with visual phenomena owing to gunshot wounds of the occipital region, have told me that bright lights, cinema exhibitions and other strong retinal stimuli tend to bring on attacks (69). |

Holmes attributed this reflex epilepsy to an enhanced excitability of the visual cortex (69).

In 1932, Radovici and associates reported the first case of eyelid myoclonia (often erroneously cited as self-induced epilepsy) with experimental provocation of seizures documented with cine film (135).

AA...age de 20 ans, presente des troubles moteurs sous forme de mouvements involontaires de la tete et des yeux sous l' influence des rayons solaires. |

In 1936, Goodkind also detailed various methods used to experimentally induce “myoclonic and epileptic attacks precipitated by bright light” in a photosensitive woman (56).

The patient was placed on a bed in a darkened room in such a position that when the black window shade was raised her face only, was directed towards the early afternoon sunlight, which came through an ordinary wire Window screen. On such exposure of the eyes to the sun, she responded within a few seconds with marked, diffuse, and apparently uncontrollable clonic jactitatory movements. The movements ceased the moment a blindfold was applied, or the black window shade was lowered. She reacted definitely also when either eye was uncovered separately… The patient was also exposed to ultra violet radiation from a quartz mercury vapour lamp, and to bright pocket flash light had little or no effect. A small beam from a carbon arc lamp produced several rapid myoclonic jerks. |

With the advent of EEG by Berger in 1929, a new era started for the study of reflex and photosensitive epilepsies (see article on visual-sensitive epilepsies).

In recent decades, the ILAE has significantly improved communication among clinicians and in clinical and basic research on epilepsy by establishing standardized classification and terminology for epileptic seizures, epilepsies, and syndromes. This work in progress provided a universal vocabulary and greatly impacted patient care. Much has changed during that time, especially regarding the concept of reflex seizures, reflex epilepsies, and reflex epilepsy syndromes, although these changes have not been straightforward. The Task Force on Classification and Terminology is constantly revising and updating the classifications according to the new knowledge. These classifications particularly affect the position on reflex epilepsies and reflex syndromes.

Reflex seizures were already included in the 1981 ILAE classification of seizures as follows (21):

Repeated epileptic seizures occur under a variety of circumstances: (1) as fortuitous attacks, coming unexpectedly and without any apparent provocation; (2) as cyclic attacks, at more or less regular intervals (eg, in relation to the menstrual cycle, or the sleep-waking cycle); (3) as attacks provoked by: (a) nonsensory factors (fatigue, alcohol, emotion, etc.), or (b) sensory factors, sometimes referred to as “reflex seizures.” |

The 1985 ILAE classification of syndromes classified “epilepsies characterized by specific modes of seizure precipitation (reflex epilepsies)” under special syndromes and commended as follows (22):

In simple forms, seizures are precipitated by simple sensory stimuli (eg, light flashes). The intensity of the stimuli is decisive, the latency of the response short (seconds or less), and mental anticipation of stimulus without effect. In complex forms, the triggering mechanisms are elaborate (eg, sight of one’s own hand, listening to a certain piece of music). The specific pattern of the stimulus, not the intensity, is the decisive factor. Latency of response is longer (in the range of minutes), and mental anticipation of stimulus, even in dreams, may be effective. |

These properties were first systematically described in the pioneering work of Forster (44).

Epilepsies with specific stimuli were defined for the first time in the 1989 ILAE classification. Precipitating seizures and precipitating factors of “syndromes characterized by seizures with specific modes of precipitation” are detailed in Appendix II as follows (23).

Precipitated seizures are those in which environmental or internal factors consistently precede the attacks and are differentiated from spontaneous epileptic attacks in which precipitating factors cannot be identified. Certain nonspecific factors (eg, sleeplessness, alcohol or drug withdrawal, or hyperventilation) are common precipitators and are not specific modes of seizure precipitation. In certain epileptic syndromes, the seizures clearly may be somewhat more susceptible to nonspecific factors, but this is only occasionally useful in classifying epileptic syndromes. An epilepsy characterized by specific modes of seizure precipitation, however, is one in which a consistent relationship can be recognized between the occurrence of one or more definable nonictal events and subsequent occurrence of a specific stereotyped seizure. Some epilepsies have seizures precipitated by specific sensation or perception (the reflex epilepsies) in which seizures occur in response to discrete or specific stimuli. These stimuli are usually limited in individual patients to a single specific stimulus or a limited number of closely related stimuli. Although the epilepsies which result are usually generalized and of idiopathic nature, certain partial seizures may also occur following acquired lesions, usually involving tactile or proprioceptive stimuli. |

According to the ILAE Glossary (14), reflex seizures are

objectively and consistently demonstrated to be evoked by a specific afferent stimulus or by activity of the patient. Afferent stimuli can be: elementary, ie, unstructured (light flashes, startle, a monotone) or elaborate, ie, structured. Activity may be elementary, eg, motor (a movement); or elaborate, eg, cognitive function (reading, chess playing), or both (reading aloud). |

In 2001, “A proposed diagnostic scheme for people with epileptic seizures and with epilepsy: report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology” was released (34). For the first time, the diagnostic scheme was divided into parts or “axes” organized to facilitate a logical clinical approach in individual patients: axis 1 = ictal phenomenology, axis 2 = seizure type, axis 3 = syndrome, axis 4 = etiology, and axis 5 = impairment. Furthermore, the terminology was again revised.

Precipitating stimuli for reflex seizures were part of the axis 2 seizure type and were listed as shown in Table 1.

• Visual stimuli | |

- Flickering light--color to be specified when possible | |

• Thinking | |

The terms “reflex seizures in generalized epilepsy syndromes” and “reflex seizures in focal epilepsy syndromes” were specifically listed as axis 2 seizure types.

Additionally, the task force defined reflex epilepsy syndrome as a syndrome in which sensory stimuli precipitate all epileptic seizures. Reflex seizures that occur in focal and generalized epilepsy syndromes that are also associated with spontaneous seizures are listed as seizure types. Isolated reflex seizures can occur in situations that do not necessarily require a diagnosis of epilepsy. Seizures precipitated by other special circumstances, such as fever or alcohol withdrawal, are not reflex seizures.

Under axis 3 epilepsy syndromes, only four distinct reflex epilepsies were delineated:

• Idiopathic photosensitive occipital lobe epilepsy |

Besides those, under the umbrella of “conditions with epileptic seizures that do not require a diagnosis of epilepsy,” reflex seizures are determined as a special entity.

The ILAE Classification Core Group report published in 2006 again evaluated the list of epileptic seizure types and epilepsy syndromes approved by the General Assembly in 2001 and considered some possible alternatives (34; 35). Regarding reflex epilepsies, the following is stated:

Reflex epilepsies: Although idiopathic photosensitive occipital lobe epilepsy, primary reading epilepsy, and hot water epilepsy in infants are syndromes, it is unclear whether other reflex epilepsies constitute unique syndromes” (35), leaving again uncertainty how to classify those entities, at that point still listed under Special epilepsy conditions. |

In 2014, the ILAE official report titled “A Practical Clinical Definition of Epilepsy” was released (42).

The task force proposed that epilepsy should be considered a disease of the brain defined by any of the following conditions: (1) at least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart; (2) one unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years; (3) diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome.

The task force elucidated the terms as follows.

Epilepsy exists in a patient who has had a seizure and whose brain, for whatever reason, demonstrates a pathologic and enduring tendency to have recurrent seizures. This tendency can be imagined as a pathologic lowering of the seizure threshold compared to persons without the condition. | |

A seizure that is provoked by a transient factor acting on an otherwise normal brain to temporarily lower the seizure threshold does not count toward a diagnosis of epilepsy. The term “provoked seizure” can be considered as being synonymous with a “reactive seizure” or an “acute symptomatic seizure.” | |

The condition of recurrent reflex seizures, for instance, in response to photic stimuli, represents provoked seizures that are defined as epilepsy. Even though the seizures are provoked, the tendency to respond repeatedly to such stimuli with seizures meets the conceptual definition of epilepsy in that reflex epilepsies are associated with an enduring abnormal predisposition to have such seizures. | |

A seizure after a concussion, with fever, or in association with alcohol withdrawal would exemplify a provoked seizure that would not lead to a diagnosis of epilepsy. The term “unprovoked” implies absence of a temporary or reversible factor lowering the threshold and producing a seizure at that point in time. Unprovoked is, however, an imprecise term because we can never be sure that there was no provocative factor. Conversely, the identification of a provocative factor does not necessarily contradict the presence of an enduring epileptogenic abnormality. In an individual with an enduring predisposition to have seizures, a borderline provocation might trigger a seizure, whereas in a nonpredisposed individual, it might not. The Definitions Task Force recognizes the imprecise borders of provoked and unprovoked seizures but defers discussion to another venue (41; 41). |

The latest official changes in the terminology were presented in 2017. The ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology published updated position papers on both the seizure types (eg, “An Operational Classification of Seizure Types”) and the classification of epilepsies that year. In those papers, reflex seizures or reflex epilepsy were not considered.

The revised framework for the classification of epilepsies used a multilevel approach, with the third level being epilepsy syndrome. Although many well-recognized syndromes were included in both the 1985 and 1989 proposals, definitions of these epilepsy syndromes have never been formally accepted by the ILAE. Following the above-mentioned publications by the ILAE Commission of Classification and Terminology, the new Nosology and Definitions Task Force was created with the main purpose of providing a means to classify and define epilepsy syndromes.

Epilepsy syndromes have been recognized for more than 100 years (a prototype can be West syndrome) as distinct electroclinical phenotypes with therapeutic and prognostic implications; thus, they were recognized as distinctive conditions long before the first International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) Classification of Epilepsies and Epilepsy Syndromes was proposed in 1985. Nonetheless, no formally accepted ILAE classification of epilepsy syndromes has existed.

Epilepsy syndromes have traditionally been grouped according to the age at onset; therefore, special working groups were established with the following divisions: (1) neonatal and infantile-onset, (2) childhood onset, (3) variable age at onset, and (4) idiopathic generalized epilepsies. A syndrome has a "variable age" of onset if it can begin both in those aged 18 years or younger and those aged 19 years and older (ie, in both pediatric and adult patients). In keeping with the 2017 Epilepsy Classification, the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology further subdivided syndromes in each age group into generalized, focal, or generalized and focal epilepsy syndromes based on seizure types and established a separate category for syndromes with developmental or epileptic encephalopathy and syndromes with progressive neurologic deterioration.

The only publication that particularly addressed reflex epileptic syndromes with the latest definition of reflex seizures comes from the paper describing epilepsy syndromes with onset at variable ages, where reflex seizure is defined as a seizure that is consistently or nearly consistently elicited by a specific stimulus that may be sensory, sensory-motor, or cognitive (140). The stimulus may be "elementary" (eg, light, elimination of visual fixation, touch), "complex" (eg, tooth-brushing, eating), or cognitive (eg, reading, calculating, thinking, listening to music). Such a stimulus will likely elicit a seizure, unlike a stimulus that may facilitate epileptiform abnormality (such as photoparoxysmal responses on EEG) or evoke a seizure but not consistently.

In that paper, only epilepsy with reading-induced seizures classified as combined generalized and focal epilepsy syndrome with polygenic etiology was considered to be a genuine reflex epilepsy syndrome (140). The task force explains not including other well-known entities in the following paragraph:

The task force considered whether disorders that result in seizures with characteristic clinical and EEG features implicating specific focal brain networks should be considered epilepsy syndromes. Although such epilepsies involving specific networks and reflex epilepsies may have a consistent constellation of symptoms and EEG findings, they lack other features that are often seen in syndromes, including specific etiologies, prognoses, and a range of comorbidities. Thus, we have not included these epilepsies as syndromes (140). |

ILAE classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in neonates and infants included myoclonic epilepsy in infancy as an entity wherein myoclonic seizures may be activated by sudden noise, startle, or touch, and less commonly by photic stimulation. Some authors proposed that the term “reflex myoclonic epilepsy in infancy” should be used if myoclonic seizures are activated by triggering factors (sudden noise or startle), stating that such patients have a slightly earlier age at onset and higher remission rate with the more favorable cognitive outcome; still, the task force did not recognize this entity as a distinct reflex epilepsy syndrome and considered it a subgroup of myoclonic epilepsy in infancy.

The ILAE classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in childhood recognized photosensitive occipital lobe epilepsy as a distinct reflex syndrome. Children, commonly between 4 and 17 years of age (although age at onset can be between 1 and 50 years), have photic-induced focal seizures involving the occipital lobe. Seizures can be induced by video games or other photic stimuli and watching analog television with slower frequency outputs.

Sartle epilepsy is no longer considered a particular reflex epilepsy syndrome, eg, not specified in any age group as such in the recent publications, and it wasn’t mentioned in the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology published in 2017. However, in 2023 it is still listed in the ILAE Online Diagnostic Manual under epilepsy syndromes regardless of age (“any age”).

Startle epilepsy is characterized by seizures that may start in childhood or early adolescence (1 to 16 years). Both sexes are affected. Most patients have an underlying structural brain abnormality with neurologic (eg, hemiplegia) and intellectual disability. Seizures are often difficult to control.

A systematic review of definitions used in the research literature for reflex and nonreflex precipitated seizures has been published (74). Koepp and colleagues provide a comprehensive review of reflex seizure, traits, and epilepsies, focusing on physiology to pathology (88). Hanif and Musick authored a comprehensive review focusing on each subtype and providing updates regarding the current scientific landscape (63).

Three excellent books are exclusively devoted to nearly all aspects of reflex seizures and related epileptic syndromes (08; 192; 186).

Reflex seizures are determined by the specific precipitating stimulus and the clinical EEG response (Tables 1 and 2) (125; 85; 88).

|

Simple somatosensory stimuli | |

|

Exteroceptive somatosensory stimuli | |

|

• Tapping epilepsy and benign childhood epilepsy with somatosensory evoked spikes | |

|

Complex exteroceptive somatosensory stimuli | |

|

• Hot water epilepsy and bathing epilepsy | |

|

Simple proprioceptive somatosensory stimuli | |

|

• Seizures induced by movements | |

|

Complex proprioceptive stimuli | |

|

• Eating epilepsy | |

|

Visual stimuli | |

|

Simple visual stimuli | |

|

• Photosensitive epilepsies (including self-induced photosensitive epilepsy) | |

|

Complex visual stimuli and language processing (language-induced seizures) | |

|

• Reading epilepsy | |

|

Auditory, vestibular, olfactory, and gustatory stimuli | |

|

• Seizures induced by pure sounds or words | |

|

Seizures induced by high-level processes (cognitive, emotional, decision-making tasks, and other complex stimuli) | |

|

• Thinking (noogenic epilepsy) | |

|

| |

The concept of precipitating stimulus. Epileptic seizures are categorized as "reactive" when they occur in response to a temporary systemic disruption, like an intercurrent illness, sleep deprivation, or emotional stress. On the other hand, they are termed "reflex" if a specific sensory stimulus consistently triggers them. The stimulus evoking an epileptic seizure is specific for a given patient and may be extrinsic, intrinsic, or both.

The response to the stimulus consists of clinical and EEG manifestations, alone or in combination. EEG activation may be subclinical only, that is, without overt clinical manifestations. Conversely, ictal clinical manifestation...

Extrinsic stimuli can be simple, such as flashes of light, elimination of visual fixation, and tactile stimuli, or complex, such as reading or eating. The latency from the stimulus onset to the clinical or EEG response is typically short (1 to 3 seconds) with simple stimuli and long (usually many minutes) with complex stimuli. Intrinsic stimuli are elementary, such as movements, or elaborate, such as those involving higher brain function, emotions, and cognition (thinking, calculating, music, or decision-making).

Response to the stimulus. The response to the stimulus consists of clinical and EEG manifestations, alone or in combination. EEG activation may be subclinical only, that is, without overt clinical manifestations. Conversely, ictal clinical manifestations may be triggered without conspicuous surface EEG changes.

Reflex seizures may be generalized, such as absences, myoclonic jerks, or generalized tonic-clonic seizures, or they may be focal, such as visual, motor, or sensory. Reflex generalized seizures occur either independently or within the broad framework of certain epileptic syndromes. In response to the same specific stimulus, the same patient may have absences, myoclonic jerks, and GTCS alone or in various combinations. Usually, absences and myoclonic jerks precede the occurrence of GTCS. Patients may have reflex and spontaneous seizures. Myoclonic jerks are by far the most common and manifest in the limbs and trunk or regionally, such as in the jaw muscles (reading epilepsy) or the eyelids (eyelid myoclonia with absences). GTCS may occur ab initio, constituting the first clinical response, or more commonly, they follow a cluster of absences or myoclonic jerks. Focal aware or impaired awareness seizures and focal to bilateral seizures are much less common than primary GTCS. Reflex absence seizures are common, constituting the response to various specific stimuli, such as photic, pattern, fixation-off, proprioceptive, cognitive, emotional, or linguistic. It is recognized that absences are also common in self-induction. Reflex focal seizures are exclusively seen in certain types of reflex focal or lobular epilepsy, such as visual seizures of photosensitive lobe occipital epilepsy or focal impaired awareness temporal lobe seizures of musicogenic epilepsy.

The electroclinical events may be strictly limited to the stimulus-related receptive brain region only (such as photically induced EEG occipital spikes), spread to other cortical areas (such as in photosensitive focal seizures that propagate in extraoccipital regions), or become generalized (eg, in photoparoxysmal responses of idiopathic generalized epilepsy). Further, the electroclinical response to a specific stimulus may correspond to the activation of regions other than the relevant receptive area, such as in primary reading epilepsy, which manifests with jaw myoclonic jerks. Conversely, reading may elicit electroclinical events strictly confined to the brain regions subserving reading, such as alexia associated with focal ictal EEG paroxysms. There is significant variability in interindividual responses to the same stimulus.

Extrinsic and intrinsic seizure triggers and common mechanisms are discussed in a review article (78). Reflex seizures are typically associated with extrinsic sensory triggers; however, intrinsic cognitive or proprioceptive triggers have also been assessed. Emotional stress is the most frequent trigger in self-reported seizure triggers. Identifying a trigger underlying a seizure may be more difficult if it is intrinsic and complex and if triggering mechanisms are multifactorial. The authors concluded, “Since observability of triggers varies and triggers are also found in non-reflex seizures, the present concept of reflex seizures may be questioned.” They suggested “the possibility of a conceptual continuum between reflex and spontaneous seizures rather than a dichotomy” and discussed “evidence to the notion that to some extent most seizures might be triggered.”

The role of EEG is fundamental in establishing the precipitating stimulus in reflex epilepsies. It allows subclinical EEG, or minor clinical ictal events, to be reproduced on demand by application of the appropriate stimulus. However, there are cases in which the stimulus-seizure relationship is difficult to document, as in video game-induced seizures. Only 70% of these patients have EEG confirmation of photosensitivity with photoparoxysmal responses on intermittent photic stimulation; in the other 30%, seizures may be due to a single or a variety of other precipitating or facilitating stimuli. Sleep deprivation, mental concentration, fatigue, excitement, borderline threshold to photosensitivity, fixation-off sensitivity, proprioceptive stimuli (praxis), or more complex visual or auditory stimuli, alone or in combination, are all possibilities that are difficult to document objectively with EEG. There are also epileptic syndromes in which EEG “epileptogenic activity” is consistently elicited by a specific stimulus with no apparent clinical relevance. This is exemplified by certain cases of benign focal childhood seizures in which somatosensory (tapping) or visual (elimination of fixation and central vision) stimuli consistently elicit spike activity, though these children appear to have “unprovoked” seizures, which mainly occur during sleep.

The ictal manifestations of reflex seizures do not differ from those of spontaneous seizures of the same type, for example, absence seizures or myoclonic seizures. Thus, reflex seizures are often classified according to the triggering stimulus; this is reflected in an international classification proposal (34). However, some typical clinical associations exist; for example, seizures induced by thinking are almost always myoclonic or clinically GTCS (Tables 3 and 4). It may also be clinically useful to think of precipitating stimuli for reflex seizures grouped according to their association with clinically generalized or bilateral EEG abnormalities or focal EEG abnormalities. However, this distinction does not constitute an element of the currently proposed classification. This is also summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

|

Clinical seizure trigger and seizure type |

Typical effective stimuli |

Region or system subserving the trigger |

|

Photosensitivity: myoclonus, absence, hypermotor seizure |

Environmental flicker, screen content |

Occipital cortex |

|

Pattern sensitivity: myoclonus, absence, hypermotor seizure |

Striped patterns, screen content |

Occipital cortex (magnocellular system) |

|

Seizures induced by thinking: myoclonus, absence, hypermotor seizure |

Mental arithmetic, block design |

Parietal lobe (nondominant or biparietal network for nonverbal visuo-spatial thought) |

|

Praxis induction: myoclonus, rarely absence, hypermotor seizure |

Typing, using a knife, action programming |

Nondominant or biparietal network for nonverbal visuo-spatial thought and Rolandic areas |

|

Primary reading epilepsy: jaw jerks, typical, myoclonus, absence, hypermotor seizure |

Reading |

Temporoparietal, predominantly dominant, or bilateral |

|

| ||

|

Clinical trigger and seizure type: all may generalize secondarily |

Typical effective stimuli |

Region or system subserving the trigger |

|

Predominantly nonlimbic: | ||

|

Induction by somatosensory stimuli, “rub epilepsy”: tonic motor, usually with initial localized aura |

Touching, rubbing, or pricking skin, often with a well-defined trigger zone, typically unilateral |

Primary or secondary somatosensory cortex |

|

Startle epilepsy: sudden startle, altered tone, supplementary motor seizure, may fall |

Startle |

Gross or subtle perirolandic lesions |

|

Seizures with eating, tooth-brushing: aura, focal motor, or focal unaware seizure |

Eating, tooth-brushing, and other oral sensory stimuli |

Perisylvian lesions |

|

Seizures with proprioceptive stimuli: typically focal motor |

Walking, movement of limbs |

Postcentral or paracentral lesions |

|

Often limbic: | ||

|

Seizures with eating: focal unaware |

Eating, taste of food |

Temporal + frontal limbic |

|

Seizures induced by experiential thought: focal unaware, focal motor |

Recall of trigger thought |

Temporal limbic |

|

Musicogenic seizures: focal unaware, focal motor |

Music |

Temporal limbic and nonlimbic |

Idiopathic generalized epilepsy and isolated reflex epilepsy. Idiopathic generalized epilepsies collectively constitute 25% of all epilepsy syndromes (111). The four distinct idiopathic generalized epilepsies include childhood absence epilepsy, juvenile absence epilepsy, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, and generalized tonic-clonic seizures alone (68). In this context, this holds significant importance when discussing reflex seizures, as more than 21% of individuals diagnosed with idiopathic generalized epilepsies will also encounter concurrent reflex seizures (118). Generalized reflex seizures, in fact, commonly manifest within the framework of idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Consequently, viewing these cases as focal reflex seizure instances with rapid secondary generalization stemming from focal or multifocal hyperexcitable cortical regions is prudent. This dynamic facilitates generalized propagation through cortico-cortical or cortico-reticular pathways.

In rare instances, isolated or predominantly focal reflex epilepsy can manifest, including photosensitive occipital lobe epilepsy, primary reading epilepsy, and startle epilepsy. Photosensitive occipital lobe epilepsy, for instance, is characterized by seizures exclusively triggered by visual stimuli, coupled with interictal occipital epileptiform abnormalities facilitated by eye closure, intermittent photic stimulation, and normal physical examinations (156). Nonetheless, it has become increasingly apparent that a subset of patients may also experience infrequent myoclonic or generalized tonic-clonic seizures, particularly with prolonged stimulation. This observation suggests this clinical entity might be a continuum between focal and generalized events.

Extrinsic stimulus-induced reflex epileptic activity, often abbreviated as extrinsic reflex epilepsy, pertains to reflex seizures triggered by various specific exogenous stimuli that impact diverse sensory-perceptual systems. Extrinsic stimuli, in this context, are sensory stimuli originating from the external environment. These stimuli encompass a range of sensory modalities, including visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, and exteroceptive inputs.

Visually induced seizures and epilepsies. Visually induced seizures and epilepsies are detailed in the MedLink Neurology articles on Visual-sensitive epilepsies, Photosensitive occipital lobe epilepsy, and Eyelid myoclonia with or without absences. Briefly, visually induced seizures and epilepsies are the most common among reflex epilepsies and compromise 5% of reflex seizures (85). Thus, this variant of reflex seizures stands as the most prevalent among all its forms, exhibiting a prevalence rate ranging from 2% to 10% within the broader population of individuals diagnosed with epilepsy. Notably, among 7- to 19-year-olds, the incidence is more than five times as common. Additionally, it is noteworthy that this particular form of reflex seizures is approximately twice as prevalent among females compared to males (64).

Visual seizures are triggered by the physical characteristics of the visual stimuli and not by their cognitive effects. Photosensitivity and pattern sensitivity are the two main categories, which frequently overlap.

As previously mentioned, numerous idiopathic generalized epilepsies commonly manifest photosensitivity as a reflex trait. For instance, various studies have reported an incidence of photosensitivity in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy of up to 90%. On the other hand, childhood absence epilepsy frequently exhibits photosensitivity as a photoparoxysmal response in 15% to 21%, without clinical effect (68). Additionally, several other syndromes are frequently linked with photosensitivity. Notable examples include Dravet syndrome, with an estimated incidence of photosensitivity in approximately 70% of cases, and Unverricht-Lundborg disease, where photosensitivity is reported in as many as 90% of affected individuals. Moreover, photosensitivity is also commonly observed in other progressive myoclonic epilepsies, such as those associated with neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis featuring CLN6 mutations and Lafora disease (118).

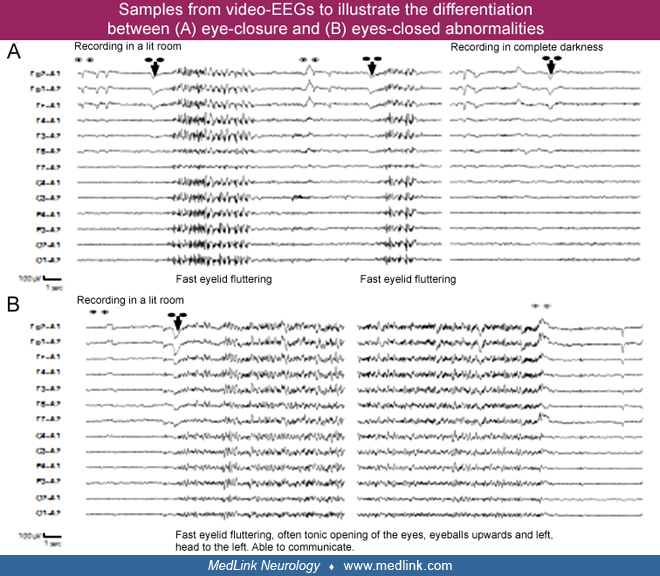

“Fixation-off sensitivity” is a term coined by Panayiotopoulos to denote the forms of epilepsy or EEG abnormalities elicited by eliminating central vision and fixation. Eliminating central vision and fixation is a specific precipitating stimulus, which, even in the presence of light, induces high-amplitude occipital or generalized paroxysmal discharges (122; 123; 124).

Photosensitive occipital lobe epilepsy. Photosensitivity is the distinguishing feature of photosensitive occipital lobe epilepsy and is much more frequent than originally appreciated after using intermittent photic stimulation in EEG testing. Photosensitivity may occur alone or progress to symptoms from other brain locations and GTCS. Extraoccipital focal seizures from the onset are exceptional. In this scenario, the primary reflex trait is video games rather than television. The symptomatology typically includes focal nonmotor seizures characterized by symptoms such as blurred vision, visual hallucinations, temporary blindness, head and eye deviation, and ictal vomiting.

Television-induced seizures. TV-induced seizures are the prevailing external stimulus responsible for provoking photosensitive seizures, and they represent the most prevalent form of photosensitive epilepsy. These seizures occur twice as frequently in females and primarily affect children between the ages of 10 and 12 years. Remarkably, around 10% of those affected by TV-induced seizures have a familial background of such seizures. Notably, 10% of individuals experiencing TV-induced seizures exhibit a phenomenon known as "compulsive attraction," wherein they are irresistibly drawn to the TV screen, almost like being pulled by a magnetic force, before progressing into a GTCS (118).

Video game-induced seizures. This phenomenon is more prevalent among boys and tends to affect individuals between the ages of 7 and 19 years. Notably, video game-induced seizures can occur not only in response to traditional TV monitors but also in association with handheld LCD displays, which suggests that the triggers for such seizures are not limited solely to television screens (124). Photosensitivity plays a dominant role in the induction of seizures triggered by video games, and it's worth noting that up to 70% of individuals experiencing video game-induced seizures exhibit genuine photosensitivity.

Seizures induced by reading and language. Epilepsy with reading-induced seizures has been recognized as a distinct reflex epilepsy syndrome in the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions paper that updated diagnostic criteria for epilepsy syndromes with variable age of onset (140). It is a rare combined generalized and focal epilepsy syndrome with age at onset in the late teens. This syndrome is characterized by reflex seizures triggered mainly by reading, but in some patients, it can also be triggered by other tasks related to language (language-induced seizures), such as talking or even writing. Spontaneous seizures are not expected.

Seizures induced by reading are detailed in the article on epilepsy with reading-induced seizures. A scoping review with a meta-analysis of reports from the last three decades has been published, including 101 case reports from 42 articles (132).

Briefly, seizures induced by reading primarily manifest with low-amplitude myoclonic jerks, mainly affecting the masticatory, oral, and perioral muscles, clinically seen as jaw myoclonus. The reading time to seizure onset varies, and if the patient continues to read, progression to generalized tonic-clonic seizure may occur. Apart from orofacial reflex myoclonus, which is present in two thirds of patients, symptoms such as visual, sensory, or cognitive, as well as the absence of seizures, can be observed. In most cases (75%), reading-induced seizures distinctly belong to reading epilepsy syndrome, although some patients have idiopathic generalized epilepsy or, alternatively, focal epilepsy. Most of the cases are males (sex ratio 2:1), and the average age of symptom onset is 18 years (132). Interictal EEG shows normal background with rare interictal discharges (133). Generalized ictal discharges are seen in approximately 75% of cases, whereas 25% show bilateral asymmetric or unilateral discharge lateralizing to the dominant hemisphere in all patients. When focal, discharges are temporo-parietal. Ictal EEG during myoclonic seizures a show short run of spikes or sharp waves, which may be of low voltage and, therefore, missed.

Many patients with reading epilepsy have similar seizures elicited by other linguistic tasks (93). Thus, reading epilepsy may be considered as a variety of more broadly defined reflex epilepsy involving a network for language (language-induced epilepsy) (93). Language-induced epilepsy encompasses seizure precipitation by speaking, reading, and writing (51). In an individual patient, the trigger may be very specific, like reading a specific language or having seizures only when reading silently and not aloud. If writing is a precipitating stimulus, hand myoclonic jerks are seen.

The seizures may be similar to those of primary reading epilepsy, and some patients report only a single effective trigger (eg, recitation alone) (66). Activation by reading and by other language tasks in the same patient can also occur in symptomatic epilepsies, as illustrated by video documentation by Canevini and colleagues (17). Language-induced epilepsy is not yet sufficiently defined to warrant classification as a separate syndrome independent of reading epilepsy. Reported cases are more heterogeneous than those of primary reading epilepsy. The prognosis is considered to be favorable with a good response to antiseizure medications. Only a minority have shown remission with age as the stimulus so important as reading can restrict daily functioning significantly.

Seizures induced by auditory stimuli and musicogenic epilepsy. The position statement by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions recognized another distinct epilepsy syndrome with a variable age of onset, in which some patients have reflex seizures precipitated by specific sounds (eg, a ringing telephone) or speech beside the spontaneous seizures (140; 16; 13). Formerly known as autosomal dominant lateral temporal lobe epilepsy or autosomal dominant partial epilepsy with auditory features, it now bears the name epilepsy with auditory features. It is a focal epilepsy syndrome with onset in previously healthy patients, typically between 10 and 30 years of age. Focal aware sensory (auditory) or cognitive seizures (receptive aphasia) are mandatory for the diagnosis. Auditory sensory symptoms are simple, unformed sounds like buzzing or ringing or less commonly complex sounds like voices or songs. Auditory distortions can also occur (alteration in the sound volume). Ictal receptive aphasia manifests as the inability to understand spoken language during a focal aware seizure. Rarely do patients report vision alteration, vertigo, or infrequent focal impaired awareness seizures or focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures. EEG is either normal or shows focal epileptiform discharges in temporal regions. Seizure outcomes range from mild seizures with early remission to drug-resistant epilepsy, especially in patients with structural lesions.

About 30% to 50% of people with autosomal dominant epilepsy with auditory features have LGI1 (leucine-rich glioma-inactivated 1) gene mutations (16; 109).

Brodtkorb reported a 23-year-old patient who had speech-induced seizures caused by an LGI1 mutation (16). He experienced short episodes of sensory aphasia in situations when he was suddenly verbally addressed. Voices became distorted, and he could not comprehend despite hearing words. During a video-EEG recording, the patient was suddenly asked for the names of his siblings. He answered but lost understanding of the further conversation and described how syllables floated together with an echoing character. With a versive movement to the right, another GTCS occurred. In the EEG, rhythmic 6-Hz activity built up in the frontotemporal areas, starting on the left side with bilateral and posterior spreading. Postictal slowing was symmetrical, and no aphasia was noted on awakening.

Additionally, an LGI1 mutation has also been reported in a patient with seizures triggered by answering the telephone (108). Telephone-induced seizures were reported in three patients who had onset during early adulthood of focal impaired awareness seizures and secondarily generalized seizures exclusively triggered by telephone answering (107). The seizures were stereotyped, with subjective auditory or vertiginous auras and an inability to speak or understand spoken voices. In one patient, a telephone-induced seizure arising from the dominant temporal lobe was recorded with video EEG. In the interictal EEGs, temporal abnormalities were detected in all cases. The patients had normal neurologic examinations and normal brain imaging.

Seizures induced by sounds or words (audiogenic epilepsy) are rare (29). Musicogenic epilepsy is the most common and best-studied form (192; 49; 84; 179; 153; 190; 131; 99; 106; 31; 37).

Musicogenic epilepsy is characterized by seizures induced by hearing certain sounds, typically music (25). Seizures have also been reported while a subject is exposed to the musical trigger during sleep or merely thinking about it. The effective stimulus can be stereotyped for each patient and at times is exquisitely specific but with no clear common pattern between patients. An affective component of the stimulus is evident in some patients. The seizures are of focal aware or impaired awareness type with interictal and ictal epileptiform activity recorded from temporal regions (147), usually the right. Most patients also have spontaneous seizures and reflex seizures that often begin over a year after the onset of spontaneous seizures (180). Musicogenic seizures have also been reported in infancy (97).

In a retrospective study of 1510 patients with epilepsy, three were found to have musicogenic epilepsy (0.0019%) (37). Significantly, two of these patients had autoimmune epilepsy with antibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase. Both patients had normal MRIs, but FDG-PET showed medial temporal lobe hypometabolism (unilateral or bilateral) in both and also in the insula in one of them. Video-EEG documented the onset of seizures from the right temporal lobe. The incidence of musicogenic epilepsy in patients with epilepsy and anti-GAD antibodies was 2 of 22 (9%). The authors concluded that the determination of anti-GAD antibodies should be carried out in all cases of musicogenic epilepsy, even those with normal structural MRI. A study by Morano and colleagues described the case of a 25-year-old man with extensive musical training who developed drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy after seronegative limbic encephalitis linked to non-Hodgkin lymphoma (110). In addition to experiencing spontaneous seizures, the patient later began to suffer from musicogenic seizures as the disease progressed.

Seizures induced by eating (eating epilepsy). Seizures induced by eating are very uncommon, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 1000 to 1 in 2000 individuals with epilepsy (112; 90), and they are characterized by seizures closely related to one or several aspects of eating (139; 90). Seizures induced by eating are usually focal motor seizures with or without impaired consciousness originating mainly from the temporal lobe, predominantly the right hemisphere, or insula or opercular region. Two different clinical types are suggested: temporolimbic, triggered by taste or smell, and extralimbic, triggered by chewing and swallowing (139) or even just thinking about the food (33; 159). Seizures originating from temporal regions have a shorter time between the act of eating and seizure onset than the seizures originating from the frontal lobe.

Eating-induced seizures are related to lesional as well as non-lesional epilepsies. Structural lesions have been previously described as more common in patients with extralimbic onset, but the latest single center study of eight consecutive patients with eating-induced seizures showed temporopolar encephalocele as the most frequent etiology (in four of eight patients) (112; 168).

Rarely, eating-induced epileptic spasms may occur (113). A boy carrying a maternally inherited MECP2 duplication had video-EEG confirmation of a cluster of eating-induced spasms, the only epileptic manifestation of the patient (26).

Rémillard and associates suggested that patients with temporolimbic seizures activated by eating have fewer spontaneous seizures and are more likely to have such episodes from the onset of their epilepsy than are patients with extralimbic, usually suprasylvian, seizure onset who have less constant activation by eating (139). Patients with suprasylvian seizure onset usually have more obvious extratemporal structural lesions and possible activation by specific thalamocortical afferents. They may also have seizures with other forms of buccal stimulation, such as toothbrushing or kissing. An unusually high occurrence of patients with eating epilepsy have been reported in two different areas of Sri Lanka by different investigators (149; 150). This could be related to genetic or ethnic factors and the bulky meals rich in carbohydrates consumed by the patients (150).

Besides MECP2 gene duplication, another genetic cause of eating-induced seizures has been described. von Stulpnagel and colleagues reported eight patients with a SYNGAP1 mutation and chewing- or eating-induced reflex seizures as a new phenotype and compared them to other patients with eating epilepsy and genetic mutations (177). They presented the clinical and anamnestic features and retrospective analysis of video-EEG data of a 4-year-old index patient with SYNGAP1 mutation and chewing- or eating-induced seizures. Clinical and anamnestic features and home videos of seven additional patients (four female; ages 4 to 14 years) with SYNGAP1 mutation and eating-induced reflex seizures were compared. All reflex seizures of the index patient showed similar focal ictal EEG patterns with high amplitude and irregular 3 Hz spike-waves with initiation from left temporo-occipital, right temporo-occipital, or bi-occipital or temporo-occipital regions, lasting 1 to 5 seconds. Eyelid myoclonia was the most common seizure type in all eight patients, and it was typically initiated by eating or other simple orofacial stimuli. In the index patient, eye closure preceded eating-induced eyelid myoclonia in most seizures (177). Ictal vomiting is a rare symptom of seizures induced by eating (163).

Orgasm-induced seizures. Also known as ictal orgasms, orgasm-induced seizures are exceedingly rare and predominantly affect women (79). These seizures are typically characterized by focal onset impaired awareness and predominantly originate from the right hemisphere. Most affected individuals experience both spontaneous and orgasm-induced seizures as part of localization-related epilepsy. These post-orgasmic seizures can manifest anywhere from minutes to hours after orgasm. Delayed seizures following climax are not associated with hyperventilation. Instead, it is believed that orgasm acts as a trigger for previously sensitized neurons within a network distributed across various regions of the brain, ultimately resulting in seizures (118).

Somatosensory stimulation-induced seizures. Seizures induced by exteroceptive somatosensory stimulation are typically triggered by touching, tapping, rubbing, or pricking body parts (102) or tooth-brushing (30). A localized or regional hypersensitive trigger zone can often be defined within the trigeminal and upper extremity somatosensory regions. The seizures are usually focal onset aware and begin with sensory symptoms (aura), followed by a sensory Jacksonian seizure with tonic motor manifestations. Subsequent generalizations may occur, but they are infrequent. Consciousness is preserved, at least at the onset.

Seizures induced by tapping, often by a single touch (“tap epilepsy”), manifest with brief reflex generalized myoclonic attacks associated with bilateral spike and wave EEG discharges (27; 171). These typically occur in otherwise normal infants and toddlers. Also, tapping is a typical and common stimulus to elicit giant somatosensory evoked responses (without clinical response) in EEG in children with SELECTs and other self-limited childhood focal epilepsies (165; 95; 126).

Seizures elicited by tapping or rubbing have been reported in some patients with cortical lesions localized in postrolandic and other regions (161; 91; 73), though normal brain MRI is more likely (83). Sala-Padro and colleagues have reported four adult patients with touch-induced seizures (142). They all had focal motor seizures after the stimuli, without impairment of awareness. Seizures were refractory to antiepileptic medication. Such seizures originated due to epileptic foci in the fronto-central regions associated with peri-central lesions on MRI.

Toothbrushing-induced seizures are a rare form of reflex seizures in patients with or without lesions (70; 117; 94; 19; 30; 65). Small lesions of the primary somatosensory cortex may be seen. Pathogenic variants in the synapsin-1 gene on chromosome X can be found in some patients (191; 143).

Stimulation of the external ear conduct (auricular epilepsy) may also elicit seizures (145). Compulsive somatosensory self-stimulation-inducing epileptic seizures have been documented in severe cases of infantile spasms (62; 164).

Diaper-changing-induced reflex seizures, although rare, are considered a possible variant of sensory reflex seizures that represent a subtype of “rub-evoked reflex epilepsy.” A case of diaper-changing-induced seizures has been described in a patient with CDKL5-related epilepsy (155) and in Dravet syndrome.

Hot water epilepsy. Hot water epilepsy, also known as “water immersion epilepsy” or “bathing epilepsy,” is detailed in the updated article on hot water epilepsy. It is not recognized as a distinct syndrome in the ILAE Classification papers published in 2022, although previously has been perceived by the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology core group as a new reflex epileptic syndrome with a relative confidence level of 2 (Table 1) (35).

Historically it was characterized by epileptic seizures elicited by pouring hot water over the head (138; 09; 125; 104; 105; 173). Two types of hot water epilepsies exist: (1) the classical hot water epilepsy seen in older children and adults and (2) a variant seen in infants now known as bathing epilepsy. Hot water-induced types of reflex seizures are among the most common reflex seizures in the pediatric population and are considered part of the same spectrum, even though clear clinical and genetic differences are recognized for each type.

Classical hot water epilepsy is known as a condition where seizures are induced by hot water (40°C to 50°C) being poured over the head and face in patients with otherwise normal development. It shows a clustering of cases in South India, although it is also reported from different countries worldwide. A significant proportion of these patients also have spontaneous seizures without a reflex component. Even though almost 20% of Indian patients have at least one family member affected by hot water epilepsy, the exact genetic mechanism is not known. The interictal EEG is usually normal; however, epileptiform abnormalities over the temporal region are observed in 20% to 25% of patients (187).

Another variant is seen in infants precipitated by immersion of the lower trunk in water with a temperature closer to body temperature (around 37.5°C). The elicited seizures have mainly autonomic features like apnea, pallor, and staring. It is worth mentioning that hot water epilepsy in infancy has been shown to have a strong clinical prediction for the future development of Dravet syndrome. Evidence suggests that bathing epilepsy is genetically distinct from the “adult” type, being caused mainly by synapsin 1 mutations.

The natural course is usually favorable as a majority of patients outgrow their epilepsy. In cases of severe early onset concomitant febrile seizures with reflex bathing seizures, the prognosis might be unfavorable if it turns out to be Dravet syndrome.

Appavu and associates described two boys with a unique form of bathing epilepsy characterized by the act of exiting water (06). The first patient had a positive family history, with a brother with frontal lobe epilepsy. He underwent an evaluation in the epilepsy monitoring unit, in which a reflex seizure was recorded while exiting the shower. This seizure was characterized by an ictal onset in the left frontal lobe and subsequent generalization. The second patient initially had nonreflex seizures from the left temporal lobe and developed reflex seizures on exiting water. For both patients, the precipitation of seizures was independent of water or environmental temperature, exposure of specific body parts, or duration of water immersion. Both children experienced a sensation of coldness, followed by convulsive or atonic activity.

Self-induced seizures. Self-induction has been well established as a mode of precipitation, but prevalence is disputed, ranging from a small number to as high as 30% of photosensitive patients. Self-induction is employed not only by intellectual disability, as it was initially reported, but also by patients of normal or above-average intelligence. Self-induction is more common in patients with photosensitive epilepsy but is also observed in other types of RE, such as hot water epilepsy. One well-known example is the “sunflower syndrome,” in which individuals gaze at a strong light source, often the sun, and deliberately move their outstretched fingers in front of their eyes. This activity generates optimal intermittent photic stimulation while also fostering a degree of pattern sensitivity. Additional self-induction practices encompass repetitive eye-opening and closing, precise head movements to induce a "rolling" effect on a TV screen, and rapid channel switching, among other actions. Patients get immense pleasure from induced seizures, which are usually absence seizures and less often myoclonic jerks. GTCS may occur due to this self-induced intermittent photic stimulation, which is probably an unwanted effect. Sexual pleasure and masturbation are exceptional. “It gives me the same pleasure as when I get a most precious Christmas gift” and “I love it, a release of tension” are common descriptions by the patients. Spontaneous seizures are not pleasurable, which indicates that the ictal enjoyment is due to the seizure-seeking behavior and maneuvers employed for self-stimulation.

Propioception-induced seizures. Simple proprioceptive stimuli (movement, including eye closure, micturition, and defecation) have been well-described as precipitants of reflex epileptic seizures. However, genuine movement-induced (kinesigenic) seizures elicited by active or passive movements are rare (28; 130; 45; 98; 172; 12; 71; 160; 39). These should be meticulously differentiated from non-epileptic paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (86; 154).

Seizure-inducing movements can involve one particular joint or a group of joints as well as the eyes, gait (gait epilepsy) (77), and, exceptionally, simple ideation of the movement. Primarily, seizures are brief, focal onset aware, and sensorimotor. This particular form manifests as a temporary occurrence in individuals with nonketotic hyperglycemia, often triggered by changes in posture or movement, and does not recur when the metabolic state improves, including insulin therapy (79). Moreover, they are described in patients with focal brain lesions in the parietal and sensorimotor cortex or supplementary motor area.

A patient with focal cortical dysplasia involving the left motor cortex had both spontaneous and arm-wrestling movement-induced, with right upper limb sensorimotor seizures with Jacksonian progression (160). Electroclinical seizure recording showed a progressive increase of spiking over the left central area, followed by recruiting rhythm and right tonic seizure. The patient became almost seizure-free after resection, without neurologic sequelae (160).

A case with video-EEG presentation was of a 78-year-old man who presented with abnormal right leg movements 2 days after mild traumatic brain injury (39). He displayed clonic movements of the right leg after a few seconds of voluntary movement of the same leg, lasting about 20 seconds. Brain MRI showed a small subarachnoid hemorrhage in the cerebral convexities. EEG at rest was normal but demonstrated robust epileptiform discharges in the left frontotemporal region figure after voluntary right leg movements.

Exceptional are seizures induced by micturition or defecation (157; 188; 53; 137; 02; 67; 178; 151; 141; 174). Seizures induced by defecation originate from the left temporal lobe (141).

Seizures induced by thinking. Seizures induced by thinking (“noogenic epilepsy”) are a rare form of reflex epilepsy and most frequently affect male adolescents (187). They occur in response to nonverbal higher cortical function and have been reported with a variety of stimuli, including arithmetic, thinking, drawing complex figures, playing cards or chess, decision-making, and solving a Rubik’s cube (182; 57; 05). Among the most consistent triggers of reflex seizures are mathematics or spatial tasks, affecting 72% of these patients (63). These seizures do not typically appear to be activated by reading, writing, or explicitly verbal tasks, but about 80% of patients are found to have more than one effective trigger. Unlike primary reading epilepsy, patients with noogenic epilepsy have spontaneous seizures.

The reflex and spontaneous seizures include bilateral myoclonus, absences, and generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Often, these begin after a period of myoclonic jerks. Still, myoclonic jerks occurred without a following GTCS in 76% of patients reviewed by Andermann and colleagues, and 60% of patients had absence seizures often associated with myoclonic jerks (05). In 68% of patients, EEG will demonstrate generalized epileptic discharges as bilateral synchronous multiple spikes and waves. Myoclonic jerks and absence seizures may be ignored or unreported until a generalized tonic-clonic seizure occurs, and the patient comes to medical attention.

Seizures induced by thinking usually occur in the context of generalized epilepsy. Focal aware seizures and clear focal EEG abnormalities have been reported, mostly right frontal or parietal regions, but are the exception (115). The essential component in the seizure trigger appears to be nonverbal thought, the processing of numeric or spatial information, and possibly sequential decision-making. One third of the patients also show photoparoxysmal discharges but not clinical photosensitivity. Studies provide more detail on the cerebral representation of calculation and spatial thought and document a bilateral functional network activated by such tasks (158). The parieto-occipital lobes might be partially involved in the neuronal network responsible for card game-induced reflex epilepsy (127). Self-induced neogenic seizures have also been reported (92).

Seizures induced by acute emotional states are relatively uncommon (136). These are usually limbic seizures with psychic aura originating in networks involved in the emotional process, with temporal lobe epilepsy being the most common, although without clear laterality or gender predominance (136). Sellal and colleagues documented a highly unusual form of epilepsy referred to as "Pinocchio syndrome," where seizures are provoked when the patient attempts to tell a lie (148).

Praxis-induced reflex seizures. The term “praxis-induction” was introduced by Japanese authors who described seizures triggered by thinking about “complicated spatial tasks in a sequential fashion, making decisions, and practically responding by using a part of the body” (75). Writing is reported to be a major precipitating factor, although reading is not (76). Hand or finger movements without “action-programming activity” (defined as “higher mental activity requiring hand movement” and apparently synonymous with praxis) are not effective triggers. Reflex upper-limb myoclonus occurs and may spread. This pattern occurs almost exclusively in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. It does not seem prominent in patients with thinking-induced seizures who do not also have prominent myoclonic reflex attacks. In its milder or most restricted forms, such as the morning myoclonic jerk of the arm manipulating a utensil, this phenomenon resembles cortical reflex myoclonus as part of a “continuum of epileptic activity centered on the sensorimotor cortex” (172). The motor component, imagined or performed, is crucial in praxis-induction. In contrast, seizures induced by thinking are activated by tasks such as purely mental calculation of orally presented arithmetic tasks with no motor component in either the stimulus or the response. Like praxis-induced seizures involving the limbs, perioral reflex myoclonias with activation of the EEG, originally believed to be significantly associated with reading epilepsy, are now recognized as typical of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (103). A patient presenting with praxis-induced myoclonic epilepsy at a late age has been reported with video-EEG documentation (54).

Startle-induced seizures and startle epilepsy. Briefly, startle epilepsy is characterized by seizures triggered by unexpected sudden sensory stimuli, usually sound or touch. In contrast to a pure sound, a sudden noise proves to be the most potent auditory stimulus. Most patients have intractable seizures, in the context of static encephalopathy, and neurologic deficits. Imaging is usually abnormal. The seizures exhibit characteristic features, typically beginning as focal onset aware seizures lasting less than 30 seconds. An initial startle response is followed by axial (central body) unilateral or bilateral tonic posturing, frequently causing falls, which can often be traumatic. Concurrent symptoms are frequently accompanied by associated autonomic phenomena, automatisms, laughter, and jerks. Less commonly, startle-induced seizures may be atonic or myoclonic, particularly in patients with cerebral anoxia. Seizures are frequent, occurring many times daily, and sometimes progressing to status epilepticus. The interictal EEG provides insights into the underlying structural brain lesion, revealing diffuse or focal abnormalities. On the other hand, the ictal EEG typically shows an initial vertex discharge, succeeded by a widespread decrease in electrical activity or the presence of low-voltage rhythmic activity at around 10 Hz (63). The prognosis is often poor, particularly for those with severe preexisting encephalopathies. Differentiation between startle-induced seizures and exaggerated startle responses can be challenging. Startle epilepsy should be differentiated from other nonepileptic disorders with abnormal responses to startling events and, mainly, hyperekplexia. Differentiation between seizures and exaggerated startle responses can be challenging. Startle epilepsy is often resistant to medical treatment. Epilepsy surgery may be beneficial to those with focal etiology of seizures.

A case of a patient with a history of generalized tonic seizures, occurring both spontaneously and in response to sudden auditory stimuli, describes possible surgery options (169). Despite multiple trials of anti-seizure medications, the condition remained refractory. The patient eventually underwent a one-stage complete callosotomy, which resulted in the remission of only the auditory-triggered seizures. Drawing from this case and the existing literature, the authors propose that the posterior corpus callosum—particularly the isthmus and anterior splenium—may play a role in seizures triggered by unexpected auditory stimuli.

The prognosis for these different seizure types depends on the underlying disorder, the degree to which stimuli can be modified or avoided, or the effect of treatment. Some patients may have only one or a few reflex seizures that can be entirely avoidable (eg, video game-induced seizures). In others, reflex seizures are controlled by avoiding precipitating factors or appropriate prophylactic medication (eg, reading epilepsy). Other reflex seizures may be lifelong and intractable (eg, progressive myoclonic epilepsies and most startle-induced seizures).

Complications are similar to those for other similar spontaneous seizures.

Researchers have investigated localization in reflex epilepsy to determine how distinct triggers correspond to specific brain areas or networks. Understanding these associations sheds light on the underlying neural mechanisms and helps identify the neuroanatomical substrates involved in different reflex seizures. Tables 3 and 4 delineate regionalizations and reflex seizures’ regional or functional triggers. The spatial distribution of physiological networks involved aligns with the posterior-to-anterior trajectory of brain development, indicating age-related alterations in brain excitability (88).

Photosensitive and pattern-sensitive reflex epilepsy involves the primary visual occipital cortex (121; 11). Subsequent studies utilizing functional MRI and magnetoencephalography have further supported the presence of regional occipital cortical hyperexcitability, distinctive regional activations, and abnormal neuronal synchronization in individuals exhibiting photosensitivity (38).

Somatosensory stimulation-induced seizures suggest a supplementary motor area seizure. Patients with tooth-brushing epilepsy have demonstrated hypoperfusion in the right mesial temporal lobe along with right hippocampal atrophy (187). Proprioceptive-induced seizures classically involve the rolandic sensorimotor area of the hemisphere contralateral to the clinical seizure onset (36).

Complex calculations have been described as the main triggers of thinking epilepsy. Simple calculations recruit only the dominant inferior frontal lobe and angular gyrus, whereas complex calculations recruit bilateral parietal lobes (79).

Reading-induced focal seizures with alexia seem to originate from the dominant supramarginal and angular gyrus (93; 48). Conversely, in primary reading epilepsy, localization may be in deep cortical and subcortical structures, particularly the left frontal piriform cortex (170). Musicogenic seizures commonly originate from the right temporal lobe (180; 50; 49).

Reflex seizures occur in epilepsies of varied etiologies, mainly genetic and structural. Traditionally, reflex seizures have been associated with idiopathic generalized epileptic syndromes where polygenic or multifactorial inheritance is suspected. Only a few causative single-gene variants have been identified in humans. Due to the improvement and availability of genetic testing, monogenic causes are increasingly recognized, and the data show that the genetic background of reflex seizures is highly heterogeneous (79; 80).

Italiano and associates published a comprehensive review of genetic determinants' role in humans and animal models of reflex seizures and epilepsies (80). The main finding was that autosomal dominant inheritance with reduced penetrance was proven in several families with photosensitivity. Molecular genetic studies on EEG photoparoxysmal response identified putative loci on chromosomes 6, 7, 13, and 16 that seem to correlate with peculiar seizure phenotypes. Autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance overlapping with a genetic background for idiopathic generalized epilepsy was also proposed for some families with primary reading epilepsy.

Musicogenic seizures usually occur in patients with focal symptomatic, mostly temporal lobe epilepsies. Occasionally, this has been reported in patients with Dravet syndrome caused by SCN1A gene mutations. Additionally, approximately 15% of patients with Dravet syndrome have photosensitivity, and photic stimuli can provoke different types of seizures. It is worth mentioning that bathing epilepsy has also been reported in patients with Dravet syndrome. Seizures triggered by hot water baths in infants have a strong association and can even be considered a clinical predictor for future Dravet syndrome. Therefore, early genetic testing for SNC1A mutations is relevant in such a clinical context.

Classical hot water epilepsy, known as a condition in which seizures are induced by hot water being poured over the head and face in patients with otherwise normal development, shows a clustering of cases in South India. However, cases have been reported from different countries worldwide.

Even though almost 20% of Indian patients have at least one family member affected by hot water epilepsy, the exact genetic mechanism is not known, and it is probably genetically heterogeneous. Autosomal dominant pedigree with reduced penetrance allowed mapping of two loci at chromosomes 4q24-q28 and 10q21.3-q22.3.

Bathing epilepsy is deemed a self-limiting type of hot water epilepsy with onset in infants. Evidence suggests that bathing epilepsy is genetically distinct from the “adult” type. It seems to be caused mainly by synapsin 1 (SYN1) mutations (01), affecting the function of this important regulatory protein in the process of neuronal exocytosis. Synapsin-1 epilepsy is frequently associated with the occurrence of reflex seizures, particularly with bathing or showering.

A four-generation family is described in the first original description of the SYN1-associated phenotype. Seven of the 10 affected male family members were of normal intelligence and had epilepsy, whereas others had various combinations of epilepsy, learning difficulties, and aggressive behavior. One of these patients with normal intelligence had episodes of “blackouts,” all occurring while in the bath. He even died in the bath, aged only 27 years (47). Later studies have proven the role of the SYN1 gene in patients with bathing epilepsy.

A distinct genetic epileptic syndrome was documented in a French-Canadian family where Q555X mutation of synapsin 1 (SYN1) gene on chromosome Xp11-q21. The syndrome was called “X-linked focal epilepsy with reflex bathing seizures.” Authors considered this phenotype to be distinctive from previously described hot water epilepsy cases due to the mode of inheritance that was clearly recessive X-linked as only male members developed epilepsy. Additionally, reflex bathing seizures also occurred out of the infancy age range; contact with water was common to all subjects, but the importance of water temperature varied, and some had seizures triggered by wiping the face with a cold wet cloth or washing the hands with tepid water. And finally, patients presented a spectrum of neuropsychological abnormalities such as dyslexia and pervasive developmental disorder (116). Pathogenic variants of SYN1 have also been reported in patients with toothbrushing and nail clipping, although less commonly (191; 143).