Epilepsy & Seizures

Tonic status epilepticus

Jan. 20, 2025

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Worddefinition

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas.

Panayiotopoulos syndrome, renamed “self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (SeLEAS)” by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions, is a common idiopathic, age- and self-limited, childhood-related, benign susceptibility to focal autonomic seizures and autonomic status epilepticus specific to childhood (117). It affects around 6% of children with nonfebrile seizures. Seizures manifest with a wide spectrum of ictal autonomic manifestations, mainly emesis, syncope-like epileptic seizures (ictal syncope), mydriasis, incontinence, and thermoregulatory and cardiorespiratory irregularities. Half of the seizures last for more than 60 minutes, often 2 to 3 hours, and, thus, constitute autonomic status epilepticus. There is marked variability of interictal EEG findings, from normal to multifocal spikes that also vary in serial EEGs. Ictal EEG onset is from the frontal or posterior regions. Seizures are infrequent in most patients; one third have a single seizure only, and half of them have two to five seizures. The remaining third of patients may have more than five seizures, and these may be frequent. Self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is a remarkably benign condition despite the high incidence of autonomic status epilepticus. Seizures are self-limiting, with remission typically occurring within a few years from onset, but probably 10% of patients may have more protracted active seizure periods. Prophylactic antiepileptic drug treatment may not be needed for most patients. Autonomic status epilepticus in the acute stage needs thorough evaluation; intravenous benzodiazepines in rectal, nasal, or buccal preparations are commonly used to terminate this nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Aggressive treatment should be avoided because of the risk of iatrogenic complications, including cardiorespiratory arrest. Self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is frequently misdiagnosed as encephalitis, atypical migraine, syncope, cyclic vomiting syndrome, and other epileptic or nonepileptic disorders. This erroneous diagnosis results in avoidable mismanagement, high morbidity, and costly hospital admissions. In this article, the author details the clinical and laboratory findings of the syndrome and provides practical guidance for appropriate diagnosis and management.

|

• Panayiotopoulos syndrome, renamed “self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures,” is a common self-limited childhood-related syndrome manifesting with infrequent autonomic seizures that often last for hours (autonomic status epilepticus). | |

|

• It is frequently unrecognized or misdiagnosed as encephalitis and other nonepileptic or epileptic disorders, which may result in avoidable mismanagement, morbidity, costly hospital admissions, and stress for child and family. | |

|

• EEG shows marked variability in the localization of spikes and may also be normal. | |

|

• Prophylactic antiepileptic treatment may not be needed. | |

|

• Out-of-hospital termination of impending autonomic status epilepticus, mainly with buccal/nasal midazolam, is highly recommended. | |

|

• Parental education is an integral and important part of management. |

Panayiotopoulos syndrome is best described as early-onset self-limited (benign) childhood seizure susceptibility syndrome with mainly autonomic seizures and autonomic status epilepticus. An expert consensus defines Panayiotopoulos syndrome "as a benign age-related focal seizure disorder occurring in early and mid-childhood. It is characterized by seizures, often prolonged, with predominantly autonomic symptoms, and by an EEG that shows shifting and/or multiple foci, often with occipital predominance" (35).

“Panayiotopoulos syndrome” was the formally approved term for this syndrome by the ILAE reports on classification (09; 19) and in the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence 2012). A number of previously used descriptive synonyms for Panayiotopoulos syndrome have been rightly abandoned, such as “early onset benign childhood epilepsy with occipital paroxysms,” “early onset benign childhood occipital epilepsy,” “nocturnal childhood occipital epilepsy.” The reason for this is that these descriptive terms are incorrect (22; 35; 14; 63; 77; 100; 99; 79; 115; 116; 129) because:

(1) Onset of seizures is mainly with autonomic symptoms, which are not occipital lobe manifestations.

(2) Of occipital symptoms, only deviation of the eyes may originate from the occipital regions, but this rarely occurs at onset. Visual symptoms are rare and not consistent in recurrent seizures.

(3) Interictal occipital spikes may never occur.

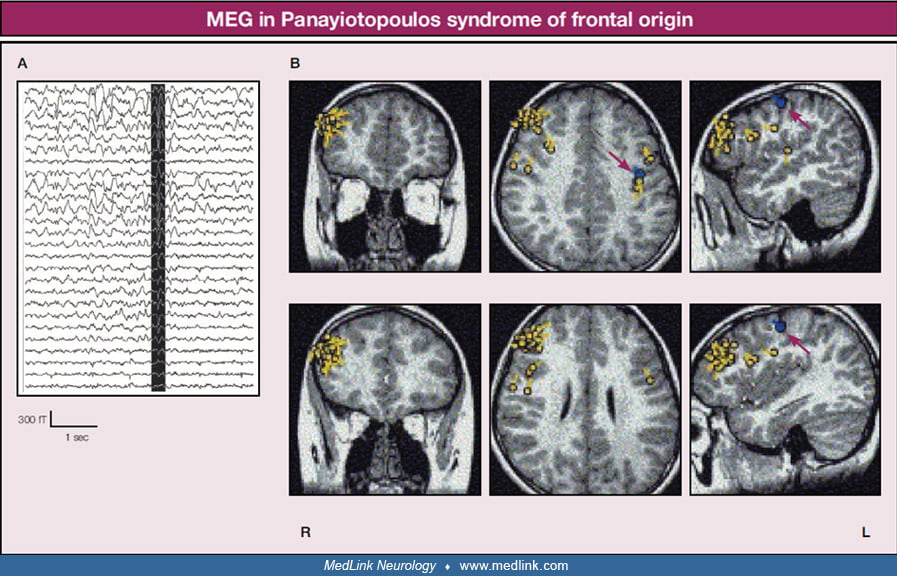

(4) Magnetoencephalography may show equivalent current dipoles clustering in the frontal areas (110) or other extraoccipital areas (55).

The patient had seizures typical of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures from the age of 4 years. EEGs initially showed occipital spikes, but at the age of 13, EEG had bifrontal spikes, and MEG was performed. The patie...

In rolandic epilepsy, equivalent current dipoles of spikes are located and concentrated in the rolandic regions and have regular directions. In self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, equivalent current dipoles of spikes...

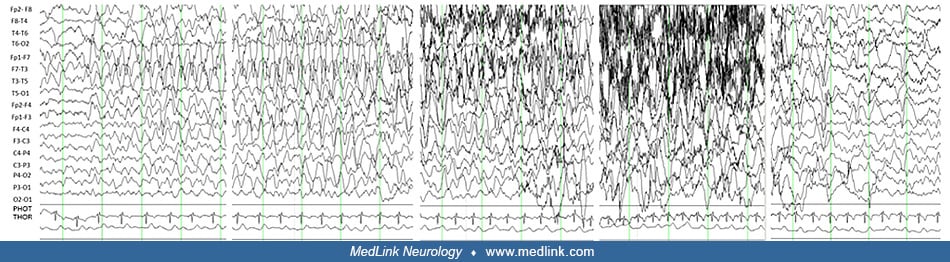

(5) Ictal EEG has documented variable onset from the posterior or anterior regions (07; 85; 128; 29; 66; 101; 53; 115; 116; 113).

(A) Spikes, spikes-slow waves are recorded frontally right more than left. (B) First clinical symptom with three to four coughs appeared 13 minutes from onset, concomitant with slow delta activity in the frontocentral regions. ...

As Martinovic pointed out, “insisting on the descriptive name ‘occipital epilepsy’ is misleading for electroencephalographers (who would seek occipital spikes that do not exist in 30% of the cases), clinicians (who would seek the conventional focal occipital seizure manifestations that do not exist in over 80% of the cases), and researchers on autonomic nervous system (who would be misinformed that the occipital lobes are the primary centers of the generations of autonomic manifestations)” (77).

Panayiotopoulos described this syndrome and autonomic status epilepticus particular to childhood in a 30-year prospective study that started in 1973 (96; 97). Initial publications included patients with EEG occipital paroxysms or occipital spikes that attracted the main attention (92; 94), but later it became apparent that the same clinical manifestations, and mainly ictal vomiting, could occur in children with EEG extraoccipital spikes or normal EEG (95).

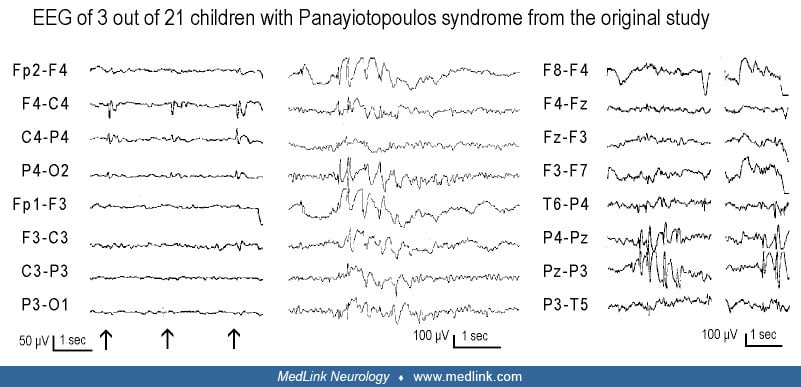

In Panayiotopoulos’ original study, ictal vomiting occurred in only 24 children out of 900 patients of all ages with epileptic seizures (93). Twenty-one were otherwise normal children (idiopathic cases constituting what is now considered self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures), and three had symptomatic epilepsies. Half of the seizures were lengthy, lasting for hours (autonomic status epilepticus). The EEGs of the 21 idiopathic cases showed great variations: 12 had occipital paroxysms or occipital spikes alone or with extraoccipital spikes; two had central spikes and giant somatosensory evoked spikes; two had midline spikes; one had frontal spikes; one had brief generalized discharges; and three had consistently normal EEG.

Extraoccipital spikes only or brief generalized discharges in three children from the original study of Panayiotopoulos (Panayiotopoulos 1988). Left: EEG for this child had centrotemporal spikes and giant somatosensory evoked s...

Subsequent attention was focused on the predominant group with occipital spikes, which was established as “early onset benign childhood epilepsy with occipital paroxysms” (94). The other group of nine children with extraoccipital spikes or normal EEGs was reevaluated much later (95); their clinical manifestations and outcomes were similar to those patients with occipital spikes. Based on these results, it has been concluded that these 21 children, despite different EEG manifestations, suffered from the same disease, which was designated as Panayiotopoulos syndrome to incorporate all cases irrespective of EEG localizations (39; 62; 63; 96; 97; 69; 86; 87; 24; 22; 23; 35; 77; 103; 100; 99; 115; 116; 80; 129; 28; 127; 78).

However, there was initial skepticism and resistance to these findings, including from influential epileptologists, for many reasons, as explained by Ferrie and Livingston (36):

• Ictal vomiting had been considered extremely rare and hitherto had been mainly described in neurosurgical series of adult patients. In children, it was generally not considered as having an epileptic origin. | |

• Autonomic status epilepticus was not recognized as a diagnostic entity; the proposition that it might be a common occurrence in a benign seizure disorder challenged orthodox concepts of status epilepticus. | |

• It implied that pediatricians had been failing to diagnose significant numbers of children with epilepsy, instead erroneously labeling them as having diverse nonepileptic disorders such as encephalitis, syncope, migraine, cyclic vomiting syndrome, and gastroenteritis (22). | |

• The characteristic EEG findings suggested alternative diagnoses. Occipital spikes suggested childhood epilepsy with occipital paroxysms of Gastaut; multifocal spikes suggested symptomatic epilepsies with poor prognosis. |

“The veracity of Panayiotopoulos’s initial descriptions has been confirmed over the last few decades in large and long-term studies from Europe, Japan and South America. The published database on which our knowledge of the syndrome is now based includes over 500 cases (79); few epilepsy syndromes are better characterized. What emerge are a remarkably uniform clinical picture and a diagnosis that is strikingly useful in helping predict prognosis and dictate management” (36).

Panayiotopoulos syndrome has been confirmed worldwide with a unique uniformity in all races and was the core theme of the June 2007 issue of Epilepsia (14; 38; 63; 72; 77; 97).

Autonomic status epilepticus, the more common type of nonfebrile status epilepticus in otherwise normal children (89), has been properly assessed in a consensus statement (38; 36).

Panayiotopoulos syndrome is detailed in the ILAE “epilepsy diagnosis” manual of the Commission and described as follows (19):

Overview. Self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (Panayiotopoulos syndrome) is characterized by the onset of autonomic seizures in early childhood that are often prolonged. The EEG commonly shows high-amplitude focal spikes and may be activated by sleep. Seizures are infrequent in most patients, with 25% only having a single seizure (which may be autonomic status epilepticus) and 50% having six seizures or less. Seizures are self-limiting, with remission typically occurring within a few years from onset.

Note. Self-limiting refers to a high likelihood of seizures spontaneously remitting at a predictable age. |

Clinical context. Self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (Panayiotopoulos syndrome) is characterized by onset of seizures between 1 and 14 years of age (majority between 3 and 6 years). Seizures are infrequent in most patients, with 25% having a single seizure (which may be autonomic status epilepticus) and 50% having six seizures or less. Frequent seizures can occur in some patients. Seizures usually resolve by 11 to 13 years of age. Both sexes are affected equally. Antecedent and birth history is normal. Head size and neurologic examination are usually normal. Development and cognition are normal. However, subtle neuropsychological deficits in language and executive functioning have been reported during active seizure periods. A history of febrile seizures is seen in 5% to 17% of patients.

Mandatory seizures. The mandatory seizure type for this syndrome is the presence of seizures with prominent autonomic features mainly emetic (nausea, retching, vomiting), but pupillary (mydriasis), circulatory (pallor, cyanosis), thermoregulatory, and cardiorespiratory (heart and respiratory rate disturbances) changes also occur. There may be incontinence and excessive salivation. Headache or cephalic auras may occur at onset. Apnea and cardiac asystole can occur, but only exceptionally are these severe. Two thirds of seizures start in sleep. Seizures are often prolonged (minutes to hours), constituting autonomic status epilepticus; however, the child recovers without residual neurologic or cognitive deficits. As the seizure evolves, loss of responsiveness, head and eye deviation, and hemiclonic activity (often with a Jacksonian march) may develop. Some seizures may have prominent fronto-parietal opercular features.

EEG background. The background EEG is normal.

Interictal EEG. A single routine EEG is normal in 10% of patients. Multifocal high voltage repetitive spikes or sharp and slow waves are seen in 90% of patients; these often are present in different focal areas on sequential EEGs. All focal brain regions may be affected, but abnormality in posterior regions is common, with occipital spikes seen on EEG in 60% of patients. Low voltage spikes and generalized discharges may be seen in a minority of cases.

Activation. Eye closure (elimination of central vision and fixation off sensitivity) may activate occipital spikes. EEG abnormality is enhanced by sleep deprivation and by sleep, when discharges often have a wilder field and may be bilaterally synchronous.

Ictal. Ictal patterns are unilateral, often having posterior onset, with rhythmic slow (theta or delta) activity intermixed with small spikes.

Imaging. Neuroimaging is normal. If the electroclinical diagnosis of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures has been made and there are no atypical features, neuroimaging is not mandatory.

Genetics. Reports of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures or other epilepsy syndromes in siblings and families suggest that genetic influences are likely complex (polygenic). There are no known genes.

Family history of seizures/epilepsy. There is usually no family history of epilepsy or febrile seizures; however, rare cases are reported with family members with epilepsy or febrile seizures.

• Familial focal epilepsy with variable foci | |

| |

The syndrome, self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (SeLEAS), formerly known as Panayiotopoulos syndrome, is childhood-related, idiopathic, self-limited susceptibility to focal, mainly autonomic seizures and autonomic status epilepticus. The children have a normal range of physical and neuropsychological development (69; 116).

Seizure characteristics. Seizures comprise an unusual constellation of autonomic, mainly emetic symptoms, often with unilateral deviation of the eyes and other more conventional ictal manifestations (39; 62; 63; 96; 97; 69; 86; 87; 22; 23; 35; 100; 99; 115; 116; 129; 133). In a typical presentation, the child looks pale, vomits, and is fully conscious, able to speak, and understand but complains of “feeling sick.” Two thirds of the seizures start in sleep; the child may wake up with similar complaints while still conscious or else may be found vomiting, conscious, confused, or unresponsive. The same child may have seizures during both sleep and awake (22; 23).

The full emetic triad (nausea, retching, vomiting) culminates in vomiting in 74% of the seizures (22; 23); in others only nausea or retching occur, and in a few, emesis may not be apparent.

Other autonomic manifestations may occur concurrently or appear later in the course of the ictus. These include pallor and less often flushing or cyanosis, mydriasis, and even less often miosis, coughing, cardiorespiratory (breathing and heart rate), circulatory (eg, pallor, cyanosis), and thermoregulatory alterations, incontinence of urine or feces, penile erection, and modifications of intestinal motility (23). Hypersalivation (probably a concurrent rolandic symptom) may occur. Headache and more often cephalic auras that may be autonomic manifestations occur, particularly at onset. Apnea and cardiac asystole may be common, but cardiorespiratory arrest is exceptional, probably occurring in up to 1 per 200 individuals with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (96; 98; 126; 35; 38; 68; 81; 31; 135). Ictal priapism has been documented in a neurologically normal 13-month-old boy in two attacks of autonomic status epilepticus of Panayiotopoulos syndrome (13).

More conventional seizure symptoms often ensue. The child gradually or suddenly becomes confused or unresponsive; exceptionally, consciousness may be preserved (6%). Eyes and often the head deviate to one side (60%), or eyes gaze widely open (12%). Other symptoms in order of prevalence are speech arrest (8%), hemifacial spasms (6%), visual hallucinations (6%), oropharyngolaryngeal movements (3%), unilateral drooping of the mouth (3%), eyelid jerks (1%), myoclonic jerks (1%), ictal nystagmus, and automatisms (1%). The seizures commonly end with hemiconvulsions, often with Jacksonian march (19%) or generalized convulsions (21%). Hemiconvulsive (2%) or generalized convulsive status (2%) is exceptional (96). However, in a report from Italy, Verrotti and colleagues identified 37 patients with convulsive or hemiconvulsive status epilepticus at the onset of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures between 1993 and 2012 (127). During the same period, 72 children with autonomic symptoms of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures without convulsive status epilepticus were found. The first episode of convulsive status epilepticus occurred at a mean age of 6.5 years. Generalized clonic seizures were the most common ictal event, and one-third of the patients required admission to an intensive care unit. Interictal EEGs showed occipital spike activity in 31 (83.7%) subjects. Only 14 (37.8%) patients were treated with valproic acid, and it was necessary to administer other drugs to two (5.40%) of them. There were no intractable cases. The overall prognosis was excellent. After the first event, 15 patients (40.54%) experienced at least another typical autonomic seizure, but all patients were seizure-free at the last follow-up (127).

Syncope-like epileptic seizures (ictal syncope) are intriguing and important ictal features of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (65). Syncope-like epileptic seizures (SLES) are defined as self-terminating events of sudden loss of postural tone and unresponsiveness, occurring either concurrently with other ictal autonomic symptoms and signs that characterize self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (AS plus SLES) or on their own (pure SLES). The child becomes “completely unresponsive and flaccid like a rag doll” before convulsions and often without convulsions or in isolation (96; 22; 23; 35; 38; 14; 65). In a report of a 6-year prospective study of children aged 1 to 15 years referred for an EEG, self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures was diagnosed in 33 of 394 consecutive children with at least one afebrile seizure (8.4%) (65). Syncope-like epileptic seizures occurred at least once in 17 of 33 children (51.5%); 12 children presented SLES in all their autonomic seizures, and five also had autonomic seizures without SLES (65). Overall, 53 of 74 autonomic seizures manifested with SLES (71.6%); 25 were AS plus SLES, and 28 were pure SLES. The latter occurred in seven children suddenly and without premonition or obvious triggers while standing, sitting, lying down, or asleep, did not resolve in the horizontal position, and were not associated with stiffening or any involuntary movements, even when longer than a few minutes. Concurrent autonomic symptoms in AS plus SLES included emesis, incontinence, mydriasis, miosis, and cardiorespiratory abnormalities.

The same child may have seizures with marked autonomic manifestations and seizures in which autonomic manifestations may be inconspicuous. The clinical seizure manifestations are roughly the same irrespective of EEG localizations, though there may be slightly less autonomic and slightly more focal motor features at onset in children without occipital spikes.

Duration of seizures. The duration of the seizures is usually longer than 10 minutes (96; 24; 35). Nearly half (44%) of the seizures last for more than 30 minutes and up to 7 hours (mean, approximately 2 hours), constituting autonomic status epilepticus (93; 16; 96; 25; 69; 86; 112; 24; 35). These seizures may sometimes persist for many hours, and the majority of these children are admitted unnecessarily to the intensive care unit, and fully investigated for metabolic and nonmetabolic disorders associated with coma (23). Of the other half (54%), duration varies from 1 to 30 minutes, with a mean of 9 minutes. Lengthy seizures are equally common in sleep and wakefulness. Even after the most severe seizures and status epilepticus, the patient is normal after a few hours' sleep (22). There is no record of residual neurologic or mental abnormalities. The same child may have brief and lengthy seizures.

Circadian distribution. In two thirds (66%) of affected children, seizures occur only during sleep, particularly the first hour of sleep. In one fifth (17.5%), seizures start while the child is awake. The remaining 16.5% have seizures both during sleep and awake. These figures may change with the inclusion of less typical cases, such as those patients who manifest with mainly ictal syncope.

Age at onset and sex. Range is from 1 year to 14 years with a consistent median around the age of 5 years (mean ± SD= 4.7±1.7 years). Three quarters (76%) occur between the ages of 3 and 6 years (96; 24; 22). Boys and girls are equally affected.

The prognosis of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures syndrome formerly known as Panayiotopoulos syndrome has been established in large-scale independent and long-term (over 5 to 20 years) prospective studies (94; 95; 96; 85; 69; 14; 33; 87; 115; 127).

Self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is a condition with a very good prognosis despite high incidence of autonomic status epilepticus (96; 35; 14; 33; 116). One quarter of patients have a single seizure or autonomic status epilepticus, and half have up to six seizures. Only 25% of cases have frequent seizures that are occasionally difficult to treat, but all have good evolution (23). Remission often occurs within 1 to 2 years of onset, but probably 10% of patients may have more protracted active seizure periods. Cumulative probability of recurrence was 57.6%, 45.6%, 35.1%, and 11.7% at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively, after the first seizure (116). The risk of developing epilepsy in adult life is probably no more than that of the general population. However, one fifth (21%) may develop other types of infrequent, usually Rolandic (13%) seizures during childhood and early teens (96). These are also age-related and remit before the age of 16 years. In 2003, it was reported for the first time that clinical manifestations of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures may occur in children with centrotemporal spikes alone, and children with Rolandic epilepsy may have seizures with concurrent ictus emeticus, indicating a close link between the two syndromes (25). Atypical evolution of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, similar to that of Rolandic epilepsy, with absences, drop attacks, and EEG continuous spike and wave during slow-wave sleep, are exceptional (15; 40; 14; 114). One fifth of children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures develop Rolandic (13%) and, less often, occipital seizures during childhood and the early teen years, but these also remit by the age of 16 years. However, though the syndrome is self-limited in terms of its seizure evolution, autonomic seizures are potentially life-threatening in the rare context of cardiorespiratory arrest (35), though all reported patients with cardiorespiratory arrest had complete recovery (31; 135). Enoki and colleagues reported four patients who originally presented with clinical features of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures in childhood and later showed development of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy in adolescence (34). Age at onset ranged from 4 to 8 years for self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and 11 to 14 years for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Whether one causes the other or whether a shared pathology is involved remains unclear.

In one report, prognostic factors for frequent seizure recurrences were studied in 79 children fulfilling the criteria of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures who were monitored for longer than 2 years (51). Medical records and EEG were analyzed retrospectively. The total number of seizures in each patient at the final follow-up ranged from 1 to 22. The 79 patients were classified into three groups: typical self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (seizure recurrence = one to five times, n = 45), borderline (six to nine times, n = 16), and atypical (more than 10 times, n = 18). Data analyzed included family history of seizure disorders, peri- and postnatal complications, previous seizure histories, age at epilepsy onset, clinical seizure manifestations, the frequency of status epilepticus, interictal electroencephalographic patterns, and the possible association of neurobehavioral disorders among the three groups. An association with preexisting neurobehavioral disorders was significantly more frequent in the atypical than in the typical group (P < 0.05), but not significantly different between the typical and borderline or between the borderline and atypical patients (P > 0.05). The authors concluded that in patients with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and preexisting mild neurobehavioral disorders, seizures tend to be pharmacoresistant and to repeat more than 10 times. However, all patients experience seizure remission by 12 years of age (51).

In one publication, An and colleagues reported the coexistence of two age-dependent focal epilepsies (one epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes; the other self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures) with an underlying brain pathology as white matter injury, not affecting the cerebral cortex, in the case of children with impaired motor skills (cerebral palsy) (03). The authors stress the importance of precisely diagnosing self-limited focal epilepsies in patients with cerebral palsy and exclusively white matter lesions. This will help to review therapeutic strategy regarding such patients and advocate for either no antiseizure or consideration of early weaning after 2 years of seizure freedom (03).

It is obvious that some children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and a very good prognosis do have neurologic and MRI abnormalities that may be as coincidental as in self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (23), or in 10% to 20% of cases, MRI may reveal structural lesions that alter diagnosis, treatment, and evolution (90).

Prognosis of cognitive function in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures was reported good, even for patients with atypical evolutions (14).

In light of the attention and emphasis on cognitive and behavioral abnormalities attributed to rolandic epilepsy and the EEG spike abnormalities (09), it is reassuring to know that the majority of children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures do not have a particularly significant risk of developing such aberrations. In a review of seven studies on neuropsychological assessments in patients with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, the overall conclusions were that children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures have normal IQ; some minor statistically significant differences were found in arithmetic, comprehension, picture arrangement, attention, and memory (116). Subtle neuropsychological deficits in some children during the active phase (46) may be syndrome-related symptoms in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, but they may also reflect the effects of antiepileptic drugs (most of the children were on antiepileptic drugs, including phenobarbital and vigabatrin) or other contributing factors. In one of the most complete investigations of visual and visuoperceptual function in 28 children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, such abnormalities were mild and uncommon (30). Bedoin and colleagues assessed voluntary orientation and reorientation of visuospatial attention in 313 healthy 6- to 22-year-old participants, 30 children suffering from rolandic epilepsy, and 13 children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (08). They found that disengagement and inhibition of visual-spatial attention were differently impaired in children with rolandic epilepsy and self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures. Children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures failed to diffuse inhibition, except in the nearest area outside the attentional focus. This deficit could be attributed to the typical occipital-to-frontal spreading of the spikes in this syndrome. Lopes and colleagues studied 19 patients (aged 6 to 12) with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (75). All patients showed normal IQ but had subtle and consistent neurocognitive impairments, such as in the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure copy task and in the Narrative Memory Test. There was no correlation between neuropsychological impairments with spike activity and hemispheric spike lateralization. The N170 face-evoked event-related potential (ERP) was normal in all patients except for one. The authors concluded that these neuropsychological findings, demonstrating impairments in visual-perceptual abilities and in semantic processing in the absence of occipital lobe dysfunction in all neuropsychological studies of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures performed to this date, support the existence of parietal lobe dysfunction. In another case study of three patients with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, it was found that they had notable impairments in visual memory tasks (x = 78), especially in comparison to verbal memory (x = 92) (52). All three patients showed increased difficulty with picture memory, suggesting difficulty retaining information from a crowded visual field. Two of the three subjects showed weakness in visual processing speed (x = 78.5), which may account for weaker retention of complex visual stimuli. Abilities involving attention were normal for all patients, suggesting that inattention is not responsible for these visual deficits. Intellectually, two of three patients had IQ's within the normal range. Academically, the patients were weak in numerical operations (x = 81) and spelling (x = 80.5), which are skills that rely on visual memory and that may affect achievement in these areas (52).

A publication provides a cross-epileptic syndromes comparison reporting on the cognitive and behavioral profile of a cohort of 32 children with childhood epilepsy centrotemporal spikes (CECTS, n = 14), childhood absence epilepsy (CAE, n = 10) and Panayiotopoulos syndrome (PS, n = 8), aged 6 to 15 years old (06). Frequent, although often subclinical cognitive difficulties involving attention, executive functions, and academic abilities were found in childhood epilepsy centro-temporal spikes and childhood absence epilepsy, and to a lesser extent in Panayiotopoulos syndrome. Internalizing symptoms (particularly anxiety) were more common in the Panayiotopoulos syndrome group compared to childhood epilepsy centro-temporal spikes and childhood absence epilepsy based on parental reports. Correlational analysis revealed a significant correlation between phonemic fluency and seizure-free interval at the time of evaluation, suggesting a beneficial effect of epilepsy remission on this executive function measure in all three groups (06).

Kanemura and associates found that status epilepticus in three children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome (two of them had convulsive status epilepticus) was associated with retarded prefrontal lobe volume growth and cognitive dysfunctions (56). No such abnormalities were observed in another three children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome but without status epilepticus.

It was reported that the neuropsychological profile of patients with Panayiotopoulos syndrome is distinctly different and worse than of those with idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut (01). Cognitive dysfunction was a more prominent and widespread feature of patients with Panayiotopoulos syndrome, whereas patients with idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut had only milder and isolated cognitive problems.

In one report, the neurocognitive functioning and behavior of 18 children (10 females, 8 males; mean age 4 years 7 months) diagnosed with Panayiotopoulos syndrome between 2010 and 2017 were analyzed retrospectively (130). They demonstrated diffuse cognitive dysfunction in full-scale IQ, performance IQ, visual attention, visual-motor integration, and verbal memory. A high incidence of internalizing behavioral problems was reported. This strongly suggests neuropsychological and behavioral comorbidity in children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome (130). Furthermore, in a study of 23 patients diagnosed with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures from a developing country, 65% reported focal seizures, 30% presented with status epilepticus, and 17% (4 of 23) had poor scholastic performance on follow-up, warranting long term follow up (67). In another retrospective study of 18 children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, 65.2% had focal seizures, and 30% had a history of status epilepticus (04). Ictal or postictal emesis was observed in all patients. Occipital spikes on electroencephalography were seen in 78%. Four children (22%) had poor scholastic performance. Although considered benign, the occurrence of status epilepticus and poor scholastic performance among some patients suggests that caution may be appropriate while prognosticating such patients (04). Seizures were well controlled with monotherapy.

However, despite the growing body of evidence supporting impairment in areas such as language, attention, and executive functions before seizures resolve, research suggests these patients are rarely referred for neuropsychological evaluation (10).

It appears that all children presenting with an epileptic event, including those with self-limited epilepsy, need an appropriate baseline assessment for a possible neurocognitive comorbidity or academic underachievement and followed-up for early intervention. Using EEG in addition to a detailed history, it is possible to distinguish self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures from nonepileptic events, acute encephalopathy, and other epileptic seizures.

Using neuroimaging techniques, particularly functional magnetic resonance imaging, could improve the accuracy of diagnosis by revealing concomitant underlying pathology and recognizing possible dysfunction of the central autonomic network. The hyperactivation of the autonomic nervous system through the central autonomic network is presumably responsible for the autonomic seizure manifestations. Identifying children prone to developing these abnormalities is crucial for the value of prediction and educational and rehabilitation procedures (142).

Case 1. This is the second of the first two cases in the original studies of Panayiotopoulos, illustrating the key and lengthy symptoms as well as the benign course of this syndrome (92; 96). A girl had two nocturnal seizures at 6 years of age. In the first fit, she was found vomiting vigorously, eyes turned to one side, pale, and unresponsive. Her condition remained unchanged for 3 hours before she developed generalized tonic-clonic seizures. She gradually improved, and by the next morning, she was normal. The second seizure occurred 4 months later. She awoke and told her mother that she wanted to vomit, and then vomited. Within minutes, her eyes turned to the right. Her mother, on her left, asked, "Where am I?" "There, there," the child replied, indicating to the right. Ten minutes later, she closed her eyes and became unresponsive. Generalized convulsions occurred 1 hour from onset. Thereafter, she recovered quickly. Her EEGs showed occipital paroxysms, but this normalized by the age of 10 years.

The patient had infrequent vasovagal syncopal episodes (retrospectively, the possibility of ictal syncope should have been considered). At last communication with her, she was 29 years of age and following a successful professional career.

Case 2. This case involved diurnal autonomic status epilepticus with behavioral disturbances that would be difficult to attribute to seizure activity before the motor partial ictal events. A 6-year-old normal boy had a seizure at 4 years of age while traveling on a train with his parents, who vividly described the event:

|

He was happily playing and asking questions when he started complaining that he was feeling sick, became very pale, and quiet. He did not want to drink or eat. Gradually, he was getting more and more pale, kept complaining that he felt sick, and became restless and frightened. Ten minutes from the onset, his head and eyes slowly turned to the left. The eyes were opened but fixed to the left upper corner. We called his name but he was unresponsive. He had completely gone. We tried to move his head but this was fixed to the left. There were no convulsions. This lasted for another 15 minutes, when his head and eyes returned to normal and he looked better, although he was droopy and really not there. At this stage he vomited once. In the ambulance, approximately 35 minutes from the onset, he was still not aware of what was going on, although he was able to answer simple questions with yes or no. In the hospital he slept for three quarters of an hour and gradually came around, but it took him another half to an hour before he became normal again. |

EEG showed occipital paroxysms and MRI was normal. A similar prolonged episode, preceded by behavioral changes, occurred 8 months later at school. He received no medication. Since then he has been well.

Case 3. Nocturnal and diurnal autonomic seizures: self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures. A 5.5-year-old female had her first episode during sleep when she vomited three times and then appeared to have gone to sleep again. Two hours later, the mother tried to wake her, but she was not responding, her eyes were turned fixed to the right, and her face was expressionless and pale. She recovered completely about half an hour later on the way to the hospital. One month later, she started having many daily episodes of tachycardia, flushed face, mydriasis, vague wondering expression, and retrosternal discomfort lasting less than a minute. During the cardiological assessment, she was found to have sinus tachycardia. During an episode, a deepening of Q wave was noticed, which was gradually returning to initial size after the episode. She was recorded by Holter, but no cardiological problems were found during the episodes. Twenty-four hour urine excretion of catecholamines was normal. During the cardiological assessment, while she was sitting, she had an episode during which she became pale and had a vague look with dilated pupils, tight mouth, and a tonic spasm that was interrupted with rectal diazepam. She was referred and assessed neurologically. The neurologic assessment was normal. During a prolonged sleep-awake video-EEG, electroclinical episodes were recorded that were compatible with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures.

A 5.5-year-old female had her first episode during sleep when she vomited three times and then appeared to have gone to sleep again. Two hours later, the mother tried to wake the child, but she was nonresponsive; her eyes were ...

An excellent homemade video shows a child with Panayiotopoulos syndrome having a seizure while traveling in a car with his family.

Case 4. This case involved seizures manifesting mainly with syncope-like epileptic seizures (96; 65). A 7-year-old boy had from 5 years of age approximately 12 episodes of collapse at school. All episodes were stereotyped but of variable duration from 2 to 35 minutes. While standing or sitting, he slumped forward, fell on his desk or the floor, and became unresponsive as if in “deep sleep.” There were no convulsions or other discernible ictal or postictal symptoms.

Four EEGs consistently showed frequent multifocal spikes predominating in the frontal regions.

Case 5. This case involved diurnal seizure with inconspicuous onset progressing to more dramatic events after sleep. A 5-year-old girl was pale and feeling unwell before leaving for school. Later that morning, her parents were informed that she was sick and retching. At home, after a brief natural sleep, she awoke with coughing and retching and asked for a glass of water. Within 10 minutes, she became unresponsive. Her eyes opened widely, and she began convulsing. Convulsions were controlled 30 minutes later with intravenous administration of diazepam. She was back to normal the next morning. EEG showed random occipital and central spikes.

Subsequently, she had an atypical evolution, as reported elsewhere (40).

Case 6. This case demonstrates that self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures can also occur with consistently normal interictal EEGs (115). At the age of 2 years, a girl had an autonomic status epilepticus during sleep. This was characterized by pallor, progressive impairment of consciousness, and vomiting that lasted 45 minutes. A second episode occurred after 11 months, during sleep, and consisted of impairment of consciousness, hypotonia, deviation of the eyes to the right, hypersalivation, and right-sided clonic convulsions. It was terminated after 45 minutes with rectal diazepam. Treatment with carbamazepine was initiated. After 6 months, she had a third episode similar to the previous ones, but shorter. At the age of 4 years 9 months, during an ambulatory EEG, she had another autonomic seizure with marked ictal EEG abnormalities, but again, the interictal did not show any spikes. Carbamazepine was replaced with phenobarbital. All 12 interictal EEGs during the active seizure period, six of them during sleep, were normal. At the last follow-up at the age of 16 years, she was well, a good student, unmedicated, and seizure-free for 11 years. See ictal EEG details in Case 4 of Specchio and colleagues’ study (115).

Case 7. A 7-year-old girl presented with a history of weekly episodes during sleep of retching occasionally culminating in vomiting or associated with incontinence of urine. During a video-EEG recording while sleeping, she had the following conventional seizure characteristic of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures: while she was sleeping lying on the left side, two seconds before seizure onset (a) she raised her head from the bed, bringing the right hand between her right ear and eyes for 2 seconds; (b) her eyes opened and turned concomitant with her head toward the left side by 180 degrees and her body by 90 degrees; (c) about 1 minute 19 seconds from the start, nausea and mild salivation were noticed; (d) and after 1 minute 40 seconds some infrequent eyelid blinking was noticed; (e) rectal diazepam was introduced at 1 minute 57 seconds, and the electroclinical symptoms seized after 9 seconds; and (f) the whole episode lasted 2 minutes and 6 seconds.

Ictal eye and head deviation with concomitant autonomic features in a 7-year-old girl with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (Panayiotopoulos syndrome). Occipital paroxysms progressively become generalized, more pre...

Self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, formerly known as Panayiotopoulos syndrome, is probably genetically determined, though conventional genetic influences may be less important than other mechanisms (121). Usually, there is no family history of similar seizures, although siblings with the same syndrome or in conjunction with rolandic epilepsy or, less commonly, with idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut have been reported (37; 25; 69; 14; 121; 91). There is a high prevalence of febrile seizures (about 17%) (96; 28). In a study of 30 patients with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, one third of them (36%) had at least one autonomic seizure triggered by fever (20). A case of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures evolving to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy has also been reported (34).

SCN1A mutations have been reported in a child (49) and in two siblings (74) with relatively early onset of seizures, prolonged time over which many seizures have occurred, and strong association with febrile precipitants even after the age of 5 years. Furthermore, a report described the variable clinical phenotypes that include the self-limited focal epilepsies of childhood, present in a large genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) family, segregating a heterozygous SCN1A missense variant (59). Sixteen of the 18 variant-positive family members were affected (88% penetrance): eight with febrile seizures, two with febrile seizures plus, one with unclassified seizures, and five with self-limited focal epilepsy of childhood. Of these, one was diagnosed with atypical childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes and four with Panayiotopoulos syndrome. This study highlights the complex genotype-phenotype correlations associated with SCN1A-related epilepsies (59). However, no such mutations were found in (a) a couple of siblings (Livingston J, personal communication), (b) homozygous twins (76) with typical self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and no febrile seizure precipitants, and (c) in 10 patients with at least one seizure of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures triggered by fever (20). These data indicate that SCN1A mutations are rare in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and, when found, contribute to a more severe clinical phenotype.

Clinical, EEG, and MEG findings of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures indicate that there is a diffuse multifocal cortical hyperexcitability, which is maturation-related (100). This diffuse epileptogenicity may be unequally distributed, predominating in one area, which is often posterior. Epileptic discharges in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, irrespective of their location at onset, activate emetic and autonomic centers prior to any other conventional neocortical seizure manifestations. An explanation for this is that children are susceptible to autonomic disorders as illustrated by the cyclic vomiting syndrome, which is a nonepileptic condition specific to childhood.

An important study from the United States assessed cardiovascular and neuroendocrine features of Panayiotopoulos syndrome in three siblings (47). Patient 1, a 12-year-old girl, had a history of involuntary lacrimation, abdominal pain, and recurrent episodes of loss of muscle tone and unresponsiveness (syncope-like epileptic seizures) followed by somnolence. Her EEG revealed bilateral frontotemporal spikes. Patient 2, a 10-year-old boy, had episodic headaches with pinpoint pupils; skin flushing of the face, trunk, and extremities; purple discoloration of hands and feet; diaphoresis; nausea; and vomiting. Tilt testing triggered a typical seizure after 9 minutes; there was a small increase in blood pressure (+5/4 mm Hg, systolic/diastolic) and pronounced increases in heart rate (+59 bpm) and norepinephrine (+242 pg/mL), epinephrine (+175 pg/mL), and vasopressin (+22.1 pg/mL) plasma concentrations. Serum glucose was elevated (206 mg/dL). His EEG revealed right temporal and parietal spikes. Patient 3, an 8-year-old boy, had a history of restless legs at night, enuresis, night terrors, visual hallucinations, cyclic abdominal pain, and nausea. His EEG showed bitemporal spikes. The authors concluded that hypertension, tachycardia, and the release of vasopressin suggest activation of the central autonomic network during seizures in familial self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (47). Secretion of vasopressin may account for the nausea and vomiting. Also, the psychomotor agitation at seizure onset likely coincides with the release of epinephrine and, to a lesser extent, norepinephrine. These ictal changes with important diagnostic and pathogenetic implications should be assessed and verified in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, considering that autonomic status epilepticus is common and often lasts for hours. See also the companion editorial by (64).

Self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and all other self-limited focal epilepsy syndromes, with rolandic epilepsy as their main representative, are probably linked due to a common, genetically determined, mild, and reversible functional derangement of the brain cortical maturational process that Panayiotopoulos proposed as "benign childhood seizure susceptibility syndrome" (95; 96; 98). The various EEG and seizure manifestations often follow an age- (maturation-) related localization (96; 98; 32). Self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is probably the early onset and rolandic epilepsy, the late onset phenotype of the “self-limited childhood focal seizure susceptibility syndrome.”

The pathogenetic links between self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and rolandic epilepsy are indicated by clinical, EEG, and MEG data (94; 95; 96; 37; 16; 14; 25; 69; 86; 55; 54; 115; 116; 113; 91). Thus, in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures:

|

• Children may also suffer from rolandic seizures either at the same or a later age. | |

|

• Seizures often have concurrent symptoms of rolandic epilepsy. | |

|

• Occipital and centrotemporal spikes, or functional spikes in other locations, may occur in the same EEG or, more often, in a subsequent EEG. On other occasions, only extraoccipital spikes are recorded. |

This child had four Panayiotopoulos-type seizures from the ages of 5 to 7 years. EEG showed occipital and other spikes with brief generalized discharges that were asymptomatic. His first two seizures were diagnosed as gastroent...

In rolandic epilepsy, equivalent current dipoles of spikes are located and concentrated in the rolandic regions and have regular directions. In self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, equivalent current dipoles of spikes...

Sakagami and colleagues described the findings in a 7-year-old girl with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures whose MRI and MR angiography were normal (111). Interictal SPECT using 99 mTc-ethyl-cysteinate dimer revealed decreased cerebral blood flow in the right occipital region corresponding to the epileptogenic focus on EEG, suggesting a focal seizure generator.

Gaddam and colleagues presented a 6-year-old female with clinical symptoms and EEG spike and wave discharges, predominantly seen over the bilateral occipital derivations occurring synchronously and occasionally independently consistent with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and diffusion tensor imaging of her brain showing attenuation of fibers over the right temporal-occipital area and decreased thickness of the right occipital lobe (42). Noncontrast brain MRI was unremarkable.

Koutroumanidis proposed that self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is a good model of "system" (nonsymptomatic) epilepsies (63).

Approximately 22% of children have self-limited (benign) focal seizures, and self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is half as common after Rolandic epilepsy (23).

Prevalence of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is around 13% of children 3 to 6 years old with one or more nonfebrile seizures and 6% of the age group of 1 to 15 years; 76% start between 3 and 6 years (96; 24; 22; 23). Of the general population of children, two to three per thousand may be affected. Boys and girls of all races are equally affected. These figures are low in epidemiological studies, probably reflecting diagnostic difficulties, misdiagnosing autonomic seizures as nonepileptic symptoms, and not including cases with atypical clinical presentations (96; 98).

In the United Kingdom, annually, there may be 751 new rolandic epilepsy cases and 233 cases of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (78).

However, contrary to all other reports, a study from North West England and North Wales found (1) the incidence of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and rolandic epilepsy to be 0.8 and 6.1 per 100,000 children younger than16 years of age, respectively, and (2) the ages at seizure onset and diagnosis were similar for both of these syndromes (131).

A report from Spain found that of 827 patients with one or more unprovoked seizures, 27 cases (3.3%) had self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (106).

Despite sound clinico-EEG manifestations, self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures escaped recognition for many years for many reasons. The main explanation for misdiagnosis is that emetic and other autonomic manifestations are often considered as nonseizure events, which is the reason for the belated recognition of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (23). Brief ictal autonomic symptoms may be misdiagnosed as atypical migraine, gastroenteritis, motion sickness, syncope, or sleep disorder (22). When these symptoms are prolonged and severe and associated with a deteriorating level of consciousness followed by convulsions, encephalitis, or other acute cerebral insults, including first epileptic event, are the prevailing diagnoses at the acute stage. Parisi and colleagues described 12 children (aged from 10 months to 6 years at the onset of the symptoms) with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures misdiagnosed as gastroesophageal reflux disease (102). Also, Carbonari and associates described four children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, 10 with temporal lobe epilepsy, and seven with West syndrome misdiagnosed as gastrointestinal disorders (18).

Roa and colleagues described an 8-year-old boy brought to the emergency department due to symptoms that began 30 minutes prior to the consultation, consisting of generalized diaphoresis, mucocutaneous paleness and dizziness, dysarthria, incoherent speech, no eye contact, and no other neurologic symptoms (loss of consciousness, abnormal movements, or sphincter relaxation) (107). At the end of the episode, which lasted 10 minutes, he presented with frontal location headache, at an intensity of 5 out of 10 with persistent nausea. Family members denied the use of toxic substances or medication; 18 months ago, he had presented a similar event, which was diagnosed as migraine. Past and family history of epilepsy were noncontributory. The neurodevelopmental milestones were according to his age. He recovered completely after 20 minutes, but during the first hours of hospitalization, he presented three consecutive and self-limited emetic events and headache that gradually improved after the administration of diclofenac 45 mg intravenously in a single dose. Hematological and biochemical profile were normal. Brain MRI was normal. A 12-hour video electroencephalogram (EEG) starting 18 hours after admission showed spike-wave complexes at 1.5 to 3 Hz with predominance in bilateral occipital regions without correlation with clinical activity. The final diagnosis was self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (107).

Katsaras and colleagues also reported a 5-year-old girl that was admitted to the pediatric emergency room (ER) due to a reported episode of vomiting during her sleep, followed by central cyanosis perorally of sort duration (< 5′), a right turn of her head, and gaze fixation with right eye deviation (57). She was dismissed after being 1-day hospitalization free of symptoms. A month later, the patient was admitted to the pediatric ER of a tertiary health unit due to a similar episode. The patient underwent EEG, which revealed pathologic paroxysmal abnormalities of high-amplitude sharp waves and spike-wave complexes in temporal-occipital areas of the left hemisphere, followed by enhancement of focal abnormalities in temporal-occipital areas of the left hemisphere during sleep. The patient was diagnosed with SeLEAS (57). Both cases stress once more the diagnostic pitfalls of the syndrome self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures formerly known as Panayiotopoulos syndrome (22; 23).

Only lately has ictal syncope been recognized as an important clinical manifestation of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures; ictal syncope may be misdiagnosed as cardiogenic syncope, pseudoseizure, or a more severe encephalopathic state (112; 22; 23; 14; 96; 2010; 103). Severe cases of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures may imitate septic shock (141).

It is alarming that physicians still may be unfamiliar with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures as indicated by the accounts of parents on the related websites (21).

Graziosi and colleagues detailed the multiple reasons and causes of misdiagnosis and pitfalls in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (48). Srivastava and Mishra reported a 5.5-year-old boy with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures who was assessed for head injury followed by vomiting, seizures, and prolonged unresponsiveness (118). Neuroimaging was normal. On detailed subsequent history, it was realized that autonomic symptoms preceded the head injury, and the interictal EEG showed bilateral occipital spikes and wave discharges with characteristic “fixation-off sensitivity.” The detailed history of events and the EEG helped to avoid misdiagnosis.

Self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is easy to diagnose because of the characteristic clustering of clinical seizure semiology, which is often supported by interictal EEG findings. The main problem is to recognize emetic and other autonomic manifestations as seizure events and not dismiss them or erroneously consider them unrelated to the ictus and a feature of encephalitis, migraine, syncope, or gastroenteritis.

This child had four Panayiotopoulos-type seizures from the ages of 5 to 7 years. EEG showed occipital and other spikes with brief generalized discharges that were asymptomatic. His first two seizures were diagnosed as gastroent...

Self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is also frequently misdiagnosed as idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut or self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (21; 100), though there is a clear distinction between them despite some overlapping clinical and EEG features (22; 23).

(1) self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut have entirely different clinical manifestations as statistically documented despite common interictal EEG when occipital paroxysms occur (Table 1). Differentiating idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut from self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures may be difficult (45; 121) when emphasis is unduly placed on individual symptoms that may overlap rather than a comprehensive synthetic analysis of their quality, chronological sequence, and other clustering features in the respective electroclinical phenotypes, which is the basis for precise differential diagnosis in clinical practice (21; 100). If any other diagnostic approach is followed, then even nonepileptic disorders, such as migraine with aura, could be deemed as overlapping with idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut (visual hallucinations and headache), self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (lengthy duration and vomiting), or both (age and family history of epilepsies). It may be because of these limitations and the retrospective character of their study that Taylor and colleagues found that only one of their 16 patients was typical in all respects of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and that idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut was as frequent as self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, which contrasts all previous prospective studies detailed in this assessment (121). Such a discrepancy may indicate that self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is still unrecognized and that the study does not represent most typical self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures patients. Further, the commonly quoted argument that self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is not essentially different from idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut, considering that “the younger the children are, the less likely they are to describe visual symptoms” (05) is not tenable: (1) more than two thirds of children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures are older than 4 years and, therefore, can describe their visual experiences and (2) there is no difference in seizure presentation between younger and older children with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures. A few patients with either self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures or rolandic epilepsy may later develop purely occipital seizures as of idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut (92; 96; 104). These cases are easy to diagnose and indicate the intimate links of these disorders within the framework of benign childhood seizure susceptibility. A 6-year-old girl presented following an episode where she brought both hands over her closed eyes and while crying she said, “I can’t, I see colors.” On the way to the hospital she vomited and then recovered. The EEG showed slow spike-wave 2 to 3 Hz in the right occipital region on eye closure, rarely on eye opening, with some spread to the left occipital region of lower amplitude. Past and family history were noncontributory. No treatment was given. The next 3 months she had a cluster of two to three episodes per cluster within half an hour, per month. She complained of seeing colors or horizontal or vertical lines in the right visual field. For the subsequent 8 months, she was free of any episode, when she relapsed again with similar episodes. During a sleep-awake video EEG, an episode was recorded. Two phases of the episode evolution are shown on video (a) and video (b).

(2) Rolandic seizures have different clinical manifestations (Table 1). Covanis and colleagues reported 24 children with EEG centrotemporal spikes and ictal emesis (25). Twenty (83%) of the 24 patients had ictal semiology typical of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, but five also had concurrent rolandic symptoms, and four later developed pure rolandic seizures. The other four patients (17%) had typical rolandic seizures with concurrent ictus emeticus. Ohtsu and colleagues found that in early-onset rolandic epilepsy vomiting usually happened in the middle of the ictus, and seizures and neurocognitive and behavioral abnormalities were more frequent, whereas focal status epilepticus and prolonged seizures were less common than in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (87).

Useful clinical note. The diagnosis of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is suspected in: (a) any child presenting with ictal emesis or other paroxysmal autonomic manifestations, particularly if prolonged; (b) any atypical, particularly nonconvulsive, febrile seizure; (c) any quick recovery after admission with the diagnosis of encephalitis; and (d) in any EEG with frequent multifocal foci from a normal child with infrequent seizures (23).

(3) In symptomatic causes of similar autonomic seizures and autonomic status epilepticus in children, there is often abnormal neurologic or mental symptomatology, abnormal brain imaging, and EEG background abnormalities. Tata and colleagues compared clinical and EEG characteristics between 24 patients with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures and 23 children with lesional symptomatic occipital epilepsy (120). Autonomic seizures (p=0.001) and ictal syncope (p=0.055) were more frequent in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures than in symptomatic occipital lobe epilepsy (87.5% and 37.5% vs. 43.5% and 13%, respectively). The age at seizure onset was significantly younger in patients with symptomatic occipital lobe epilepsy than in those with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (mean age at onset: 3.4 vs. 5.6 years, respectively; p=0.044). The interictal spike-wave activity increased significantly during non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) sleep in both groups. The spike waves in non-REM seen in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures tended to spread mainly to central and centrotemporal regions (120). A case of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis masquerading as self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures has been published (02).

Furthermore, autonomic seizures mimicking self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures may occur in children with fragile X syndrome (12) and 22q11 deletion syndrome (11).

(4) Cases of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures may be diagnosed as febrile seizures when seizures occur when the child has a febrile illness or because of ictal thermoregulatory changes.

(5) Photosensitive occipital seizures may have similar symptoms of autonomic disturbances and ictal vomiting, but elementary visual hallucinations and other manifestations of visual seizures usually precede these (50; 105).

|

Panayiotopoulos syndrome |

Rolandic epilepsy |

Gastaut-type idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy | |

|

Prevalence in children aged 1 to 15 years with afebrile seizures (%) |

6% |

15% |

approximately 1% |

|

Mean age at onset (range), years |

4 to 5 (1 to 15) |

7 to 8 (1 to 15) |

10 to 11 (4 to 17) |

|

Male/female ratio |

1 |

1.5 |

1 |

|

Main seizure symptoms at onset |

Emesis and/or other autonomic disturbances |

Facial sensorimotor, speech arrest |

Elementary visual hallucinations or blindness |

|

Common duration of seizures |

> 9 min |

1 to 3 min |

Seconds to < 1 min |

|

Total number of seizures in most patients (% single) |

1 to 5 (30) |

1 to 10 (20) |

Hundreds (0) |

|

Circadian distribution (%) |

Nocturnal (64%) |

Nocturnal (70%) |

Diurnal (100%) |

|

Focal nonconvulsive status epilepticus (> 30 min), % |

40% |

Exceptional |

Exceptional |

|

Febrile convulsions, % |

17% |

10% to 20% |

Unknown |

|

Common interictal EEG spike location |

Multifocal |

Centro temporal |

Occipital |

|

Onset of ictal EEG |

Posterior or anterior brain regions |

Lower part of pre and postcentral gyrus |

Occipital |

|

Prognosis |

Excellent |

Excellent |

Unpredictable: 70% remit |

Improving diagnostic yield. Seizure clinical manifestations are probably more important than EEG (21; 116). By increasing awareness, diagnosis is expected to improve (21; 48). Referrals are often vague and include encephalitis, atypical migraine, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastroenteritis, or first prolonged seizure. The contribution of EEG technologists is crucial (112). In an ongoing prospective study at the end of 3 years, 228 consecutive children aged 1 to 14 years had one or more epileptic seizures. Fourteen patients (6.1%) had self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures diagnosed mainly on clinical grounds. This did not include 11 additional patients with possible self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, either with atypical clinical and EEG features or inadequate information. Of the 14 children with typical self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, only three were appropriately diagnosed on referral. Alarmingly, nine patients were suspected of suffering from encephalitis, a diagnosis that demanded further invasive procedures such as lumbar puncture, erroneous treatment, and costly hospital admissions. For most of the patients, the correct diagnosis and management was prompted by the EEG technologist who obtained the appropriate history through a simple questionnaire while preparing the patient for an EEG (112).

The diagnosis of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures is based on the history, the presented symptoms, and the support of a sleep-awake (video) EEG after sleep deprivation. The EEG will also help to differentiate self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures from other syndromes and also nonepileptic events.

However, because of its high prevalence, self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures may incidentally occur in children with neurocognitive deficits or abnormal brain scans (134; 36; 136; 71). The most useful laboratory test is EEG, particularly a sleep-awake EEG combined with a detailed history (96; 22; 14; 63; 87; 100). Implementing functional neuroimaging techniques could improve the accuracy of the diagnostic process because in some rare cases, causal brain injuries will be detected (90; 27; 44).

In one publication, An and colleagues reported the coexistence of two age-dependent focal epilepsies (one epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, the other self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures), with an underlying brain pathology as white matter injury, not affecting the cerebral cortex, in the case of children with impaired motor skills (cerebral palsy) (03). The authors stress the importance of precise diagnosing of self-limited focal epilepsies in patients with cerebral palsy and exclusively white matter lesions. This will help to review therapeutic strategy regarding such patients and advocate for either no antiseizure medication or consideration of early weaning after 2 years of seizure freedom (03).

The main determinant of the neurodiagnostic procedures is the state of the child at the time of first medical attendance:

(1) The child has a brief or lengthy seizure of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures but fully recovers prior to arriving in the accident and emergency department or being seen by a physician. A child with the distinctive clinical features of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, particularly ictus emeticus and lengthy seizures, may not need any investigations other than EEG. However, because approximately 10% to 20% of children with similar seizures may have brain pathology, an MRI may be needed.

(2) The child with a typical lengthy seizure of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures partially recovers while still in a postictal stage, tired, mildly confused, and drowsy on arrival to the accident and emergency department or when seen by a physician. The child should be kept under medical supervision until fully recovered, usually after a few hours of sleep. The guidelines are the same as in (1) above.

(3) The child is brought to the accident and emergency department or is seen by a physician while ictal symptoms continue. This is the most difficult and challenging situation. Dramatic symptoms may accumulate in succession, demanding rigorous and experienced evaluation. A history of a previous similar seizure is reassuring and may prevent further procedures.

Electroencephalography. EEG commonly (90%) reveals functional, mainly multifocal, high amplitude, sharp and slow wave complexes. Sleep typically attenuates spike abnormalities. EEG is indispensable in diagnosing patients with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures if clinical information is inadequate or emetic manifestations are inconspicuous.

Electroencephalographers should be alerted by frequent multifocal spikes of a normal child with one or a few seizures.

Extraoccipital spikes only or brief generalized discharges in three children from the original study of Panayiotopoulos (Panayiotopoulos 1988). Left: EEG for this child had centrotemporal spikes and giant somatosensory evoked s...

This child had four Panayiotopoulos-type seizures from the ages of 5 to 7 years. EEG showed occipital and other spikes with brief generalized discharges that were asymptomatic. His first two seizures were diagnosed as gastroent...

There is a great EEG variability of functional focal spikes at various electrode locations (93; 95; 96; 85; 25; 69; 86; 112; 14; 61; 115; 116). All brain regions are involved, though the posterior regions predominate. Occipital paroxysms prevail but do not occur in a third of patients. In a study of 43 cases with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, occipital spike localization was recorded in 29 (67%) patients, nine (21%) patients with typical clinical features had completely normal EEGs despite two to four repeated recordings per patient performed during sleep and wakefulness, and the remaining five patients (12%) never had occipital spikes despite three to six EEGs per patient. Instead, there were rolandic spikes in two patients or rare, brief bursts of generalized 3- to 3.5-Hz spike-and-wave discharges and photosensitivity in three patients (69).

In another study of 47 cases with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, two thirds (68%) had at least one EEG with occipital spikes, which were often (64%) concurrent with extraoccipital spikes also in at least one EEG. The other third (32%) never show occipital spikes; instead they have extraoccipital spikes (21%) only, consistently normal EEG (9%), or brief generalized discharges only (2%). EEG with multifocal spikes in more than two and often many brain locations occur in one third (30%) of the patients; single spike foci are rare (9%) (96). Clone-like repetitive multifocal spike-wave complexes may be characteristic features when they occur (19%) and may be frequent in certain cases with only few autonomic seizures or autonomic status epilepticus and do not affect cognition (96).

In routine EEG, these spikes appear to occur simultaneously at various locations in one or both hemispheres, but usually they are driven (secondarily activated) by a primary spike generator, which is predominantly posterior; they may lead the other spikes by a few milliseconds and may also be the smallest of all or inconspicuous (96; 72; 70; 61). These are probably pathognomonic of the syndrome if recorded from otherwise normal children with a few epileptic seizures (96; 132). They have never been studied or reported before in idiopathic epilepsies. On the contrary, multifocal repetitive spikes are considered to indicate a bad prognosis and a symptomatic etiology. Cloned-like repetitive multifocal spike-wave complexes do not determine prognosis as they equally occur in children with one or more seizures.

A study examined the spatiotemporal course of interictal spikes, particularly whether seemingly independent extraoccipital spikes are truly autonomous or secondary, triggered by occipital spikes (61). It was found that the patterns of spatial and temporal dynamics of the interictal spikes were not stereotypical for any brain area, including the occipital lobe. Some anterior and posterior spikes remained focal or showed little spread, but others appeared to propagate to the opposite direction (occipital to frontal and vice versa). The authors concluded that in self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, all cerebral locations can spontaneously and independently generate and propagate interictal spikes, indicating that this is a multifocal epileptic syndrome.

Spikes are usually of high amplitude and morphologically similar to the centrogyral (rolandic) spikes. They often show stable dipoles in the occipital regions (140; 139; 138). However, small and inconspicuous spikes may appear in the same or previous EEG of children with giant spikes. Though rare, small positive spikes or other unusual EEG spike configurations may occur.

In more than half of patients with self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures, a small positive spike precedes either the rolandic or occipital spikes, and this may indicate increased levels of epileptogenicity, but this needs further studies (137). Similarly, it has been found that spike-related high-frequency oscillations (mainly in the ascending phase of the spikes) occur during the period of active seizures in rolandic epilepsy and self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (60; 88).

Brief generalized discharges intermixed with small spikes may occur either alone (4%) or, more often, with focal spikes (15%). In a report, Caraballo and associates found that 9 of 150 children with typical clinical features of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures had on EEG only diffuse paroxysms at onset that continued along the course of the syndrome. From a clinical point of view, other features were otherwise unremarkable. Diffuse spike-and-wave discharges were observed in all patients when awake and during sleep (100%). Later, three children also had focal spikes during sleep, which were occipital in one, frontal in one, and temporooccipital in the remaining patient. Spikes were activated by sleep in all three cases. During disease evolution, no particular electroclinical pattern was observed. The course was benign. Clinical features and evolution were similar to those of typical cases of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (17).

The EEG spikes may be stimulus sensitive; occipital paroxysms are commonly (47%) activated by elimination of central vision and fixation, whereas centrogyral spikes may be elicited by somatosensory stimuli. Coexistence of fixation-off sensitivity and inverted fixation-off sensitivity is extremely rare (108). Occipital photosensitivity is an exceptional finding.

Functional spikes in whatever location are accentuated by sleep. If a routine EEG is normal, a sleep EEG should be performed. There is no particular relationship between the likelihood of an abnormal EEG and the interval since the last seizure. EEGs shortly or long after a seizure are equally likely to manifest with functional spikes that may occur only once in serial routine and sleep EEGs.

The background EEG is usually normal, but diffuse or localized slow-wave abnormality may also occur in at least one EEG of 20% of patients, especially postictally.