Epilepsy & Seizures

Tonic status epilepticus

Jan. 20, 2025

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Worddefinition

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas.

In this article, the author describes the clinical characteristics of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder. Sleep-related rhythmic movements are common in infants and children. The pathogenesis of sleep-related rhythmic disorder is likely to be multifactorial, possibly involving emotional, vestibular, and sleep-related emergence of archaic motor pattern activity through the activation of the central motor pattern generators in the brainstem. These factors may prevail over one other in the different forms of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder and with respect to the stage during which the disorder arises (sleep/wake transition, NREM sleep, or REM sleep).

At times, these movements are excessive and may disrupt sleep, resulting in daytime sleepiness or injury. In these cases, the movements are classified by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition (ICSD-3), as a sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder.

|

• Sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder consists of repetitive, stereotyped, and rhythmic motor behaviors (not tremor) that involve large muscle groups, such as in head banging and rocking or rolling of the head or body, with a rate range of 0.5 to 2 per second. | |

|

• Sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder is distinguished from developmentally normal sleep-related rhythmic movements by the presence of associated sleep disturbance, impairment of daytime function, or self-inflicted bodily injury. | |

|

• The movements occur at bedtime or near naptime when the patient is drowsy or may occur during any stage of sleep, including REM sleep. | |

|

• Sleep-related movements usually occur in infants and young children. However, cases of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder have also been reported in adults, both as adult-onset forms or relapse forms of prior infantile sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder. | |

|

• Although there are no well-established therapies, there are case reports of significant improvement of rhythmic movements and sleep quality with the use of benzodiazepines, antidepressants, behavioral interventions, hypnosis, and/or sleep restriction. |

Repetitive head banging during sleep was first described by Zappert in 1905 and termed “jactatio capitis nocturna.” At the same time, Cruchet of France termed it “rhythmie du sommeil.” The terms “head banging,” ‘head rolling,” body rocking,” “body rolling,” and jactatio corporis nocturna” have also been applied to describe the movements. This condition was named “rhythmic movement disorder” by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) in 1990 to include the different rhythmic movements that occur in sleep (06). It was initially classified in the parasomnia section under the subcategory of sleep-wake transition disorders because the movements were thought to occur exclusively during the transition between wake and sleep.

In 2005, the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition (ICSD-2) renamed the condition “sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder” or “RMD” to stress that these movements are associated with sleep and to avoid confusion with the stereotypic rhythmic movements or “stereotypic movement disorder” (DSM 4 and proposed DSM 5) that occur during the daytime (05; 03). Stereotypic movement disorder consists of daytime potentially injurious, repetitive, seemingly driven, and apparently purposeless motor behaviors, such as handshaking, waving, body rocking, head banging, and self-biting, that cause clinically significant distress and impairment of function. The compulsions seen in obsessive-compulsive disorder, tics seen in tic disorder, and stereotypies seen in children with autistic disorder are not classified as either stereotypic movement disorder or sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder.

In 2005, ICSD-2 also reclassified sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder under the nosological category of “sleep-related movement disorders,” which includes restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, sleep-related bruxism, sleep-related leg cramps, unspecified sleep-related movement disorder, and sleep-related movement disorder due to drug or substance or due to medical condition. ICSD-3 (04) expands “sleep-related movement disorders” to also include benign sleep myoclonus of infancy and propriospinal myoclonus at sleep onset.

Interestingly, in 1937, almost 60 years before sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder was recognized by the ICSD, it was depicted in Walt Disney’s film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (32). One of the seven dwarfs, Dopey, is noted to have repeated rhythmic back-and-forth myoclonus-like thrusting movements of the head, accompanied by soft vocalizations, after laying down to sleep. When he is touched, the movement subsides as he opens his eyes, and he goes back to sleep with a happy sigh.

Sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder is characterized by repetitive, stereotyped, and rhythmic motor behaviors (not tremor) of large muscle groups with a rate of 0.5 to 2 per second, which occur during drowsiness or sleep. These movements are common in infants and young children and are thought to be related to the soothing effect of vestibular stimulation caused by the rhythmic movements. The presence of significant clinical consequences such as interference with normal sleep, significant impairment in daytime function, or self-inflicted bodily injury that requires medical treatment (or would result in injury if preventable measures were not used) is what differentiates sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder from normal sleep-related movements (04).

Subtypes of movements include the following:

|

• Body rocking usually involves the entire body with the child on hands and knees, or it may involve only the torso with the child sitting and rocking back and forth. | |

|

• Head banging usually occurs with the child lying prone and involves lifting of the head and, at times, the upper torso and then forcibly banging the head down on the pillow or mattress. The child may also sit with his back to the wall or headboard and repeatedly bang the occiput back and forth. | |

|

• Head rolling consists of side-to-side head movements, usually with the child lying supine. | |

|

• The combined type involves two or more of the individual types. For example, body rocking and head banging may also be combined so that the child rocks back and forth and bangs the head simultaneously. | |

|

• Other movements include body rolling, leg banging, or leg rolling. Hand banging has also been reported but is less common. Different types of rhythmic movements may occasionally occur in the same individual during the same night (31; 47; 58). |

A case of an atypical form of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder consisting of head banging with punching or slapping the head with a hand has been reported (34). This case is very similar to the three reported by Yeh and Schenck in 2012 (70).

The episodes usually last less than 15 minutes, but the duration may vary from a few minutes to an hour, with a frequency of 0.5 to 2 per second. Rhythmic humming may be heard along with the movements (03). The movements and the associated sounds may be loud. Environmental noise or distractions during the movements may lead to cessation of the event. These movements are usually more concerning and bothersome for the family and bed partner than for the patients themselves. The patient is usually unresponsive during the events and may have no recollection on awakening.

Episodes of sleep-related rhythmic movements were initially reported to occur when drowsy near sleep onset and during transitions between sleep and wake. However, this was before polysomnographic studies were done. It is now known that movements associated with sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder may occur during quiet wakeful activities, such as listening to music or riding in a vehicle, and during any stage of sleep (03; 04). Sleep-related movements arising from an unstable, difficult-to-define NREM stage were reported in a case of rhythmic movement disorder and sleep terror comorbidity in a 3-year-old boy (46). Sleep state-specific associations with rhythmic movement subtype have been reported (51), with rolling movements being significantly associated with REM sleep stage and rocking movements with superficial NREM sleep, independently of age.

In 2002, Koyhama and colleagues summarized literature from previous polysomnographic studies from 33 patients with sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder and reported that sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder occurred during all stages of sleep, including slow-wave sleep and REM sleep (36; 07). Eighteen of the patients had episodes in REM sleep, with the episodes occurring exclusively during REM sleep in eight of them. The authors also reported two children in their study that manifested episodes during all sleep stages. Sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder has also been strongly linked with the A phase of cyclic alternating pattern during NREM sleep stage N2 (44).

Typical cases of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder in infants and toddlers are not associated with a significant risk of injury. When injury occurs, it is noted mostly in headbangers and can be variable in type. “Headbanger tumor” describes soft tissue swelling that occurs at the forehead. MRI changes in headbangers have been reported, including enlargement of the diploic space in the parietal and occipital bones with loss of adjacent gray matter (12).

There are several case reports of nocturnal tongue biting, including a 2-year-old girl with recurrent nocturnal tongue biting associated with rhythmic jaw movements (63). When tongue biting is present, frontal lobe seizures should be considered in the differential diagnosis (64). There is also a case report of Hirayama disease associated with severe rhythmic flexion movements of the neck in a 10-year-old girl (33). Hirayama disease is a flexion myelopathy resulting from compressive flattening of the lower cervical cord and forward displacement of the cervical dural sac and spinal cord caused by neck flexion. Finally, an odontoid fracture was diagnosed by neck x-rays in a 65-year-old woman with head banging and osteopenia complaining of neck pain (71).

Roethlisberger and Zubler reported a case of isolated mandibular sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder (53).

Most individuals with sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder are otherwise normal children and adults. However, sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder has been found to be associated with sleepwalking and daytime sleepiness in school-aged children (49). Significant daytime sleepiness may also be seen in adults with frequent episodes (16). There are reports of an increased association of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder with temper tantrums and attention deficit disorder in Spanish school-aged children, especially those with low ferritin levels and headaches (09; 61; 62; 67; 17). One study showed that college students who engage in body rocking have higher levels of general distress and a higher prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder (52). Body rocking in these individuals usually started in childhood. Several studies link sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder persisting into adulthood with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, restless legs syndrome, and sleep apnea (56; 15; 23; 65). A case series of five adults with sleep apnea-related rhythmic movement disorder has been reported (14). Sleep-related rhythmic movements mostly occurred in association with obstructive respiratory events, especially during stage REM sleep, and they proved to recover in one patient after continuous positive airway pressure therapy. The hypothesis was that sleep apneas may trigger rhythmic motor events through a respiratory-related arousal mechanism in genetically predisposed subjects.

In a questionnaire-based and 3-night home video polysomonographic plus 5-night actigraphic study, Kose and colleagues found a significantly higher prevalence of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder in Down syndrome subjects compared to healthy controls (37). In Down syndrome with sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder, sleep proved to be of poor quality and low efficiency. The link between sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder and Down syndrome is of uncertain origin, though neurocognitive impairment and developmental delay are thought to play a role.

Vitello and colleagues reported a 44-year-old patient with a history of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder that persisted into adulthood consisting of rhythmic movements of the limbs, head rolling, and severe body rocking associated with groaning that caused him to sleep alone (65). He also reported typical restless legs symptoms since childhood, including an urge to move the legs that was relieved by movement. He reported a family history of restless legs syndrome but not sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder. He was not sure whether restless legs syndrome or sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder started first but felt that his rhythmic movements helped him relieve his restless legs syndrome symptoms. He was treated with clonazepam without success but responded to a trial of pramipexole.

In a retrospective study of 50 patients with rhythmic movement disorder, Laganière and colleagues reported a high rate of complaints of disturbed nocturnal sleep (82%) as well as comorbidities (92%) (39). Polysomnography documented altered sleep continuity, low sleep efficiency, increased wake time after sleep onset, and frequent periodic leg movements and apnea events, with the severity of rhythmic movements being associated with the degree of disrupted nighttime sleep after controlling for comorbid motor and respiratory events.

There are also reports of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder associated with REM sleep behavior disorder. In one case, the patient had a childhood history of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder and later developed idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder as an adult (69). The rhythmic movements were seen predominantly in REM sleep and persisted despite successful treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder with clonazepam. In the other two cases, rhythmic movements in REM sleep were observed in two adults as an integral part of motor manifestations of REM sleep behavior disorder episodes (43). Both patients had no childhood history of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder. Although the association is unclear, the mesencephalon, pons, and spinal cord are the sites of loss of muscle control seen in REM sleep behavior disorder. This is also the site of the so-called central pattern generators (24). Central pattern generators are a genetically programmed network of neurons that may be involved in generating motor patterns seen in sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder.

A reappraisal of the clinical and pathophysiological features of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder has been done (27). The developmental course of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder is stressed, with typical forms of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder starting in infancy and spontaneously resolving in early childhood and some forms being associated with neurodevelopmental disorders, namely attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The need for understanding the pathophysiology of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder forms with persistence or relapse in adult life is underlined.

Sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder typically occurs in infants and toddlers, and it usually resolves in the second or third year of life with a prevalence of 5% by 5 years of age (04). Even when the disorder persists into adolescence or adulthood, complications are rare, other than embarrassment. However, sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder has been found to be associated with sleep-onset insomnia, sleepwalking, and daytime sleepiness in both children and adults (16; 49). As described earlier, injuries have also been reported, especially in headbangers, including minor head trauma, headbanger tumor, tongue injury, odontoid fracture, and Hirayama disease (63; 12; 33; 71). Recurrent subdural hematoma was reported to occur in a case of headbanging (50).

When sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder persists in older children and adults, it is more likely to be associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, headaches in school-aged children, temper tantrums, restless legs syndrome, REM sleep behavior disorder, and sleep apnea (09; 56; 61; 67; 23; 69; 65).

In a systematic review including seven manuscripts (n = 32 individuals), Michalek-Zrabkowska and colleagues reported that clinical manifestations of body or head rolling predominated in most of the cases and that insomnia, restless legs syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea, ischemic stroke, epilepsy, hypertension, alcohol and drug dependency, mild depression, and diabetes mellitus were not infrequently comorbid with rhythmic movement disorder (48).

A 5-year-old boy presented to the sleep medicine clinic with complaints of restless sleep, irritability, growing pains, and body rolling. The mother stated that the movements started with head rolling at 6 months of age, occurred during sleep onset, and occurred 10 to 12 times throughout the night. More recently, body rocking and rolling movements occurred during sleep onset for up to an hour, with nocturnal awakenings. The movements had resulted in bruising in the past; subsequently, the mother routinely put extra pillows around his bed so that he would not injure himself against the wall or headboard. The mother was concerned that her son was sleep-deprived, and the grandmother was concerned about epilepsy.

The child was born full-term and did not have other medical problems. He was developmentally on track, socially appropriate, and growing well with a normal appetite. On further questioning, he described leg and arm discomfort (“feels like soda”) at night, which was relieved with movement.

His vitals were normal. His height and weight were at the 50th percentile for age. The physical exam was normal, including an absence of bruising or signs of injury. Neurologic examination was normal.

Laboratory findings included a ferritin level of 28 ng/mL (low, but within laboratory normal range). Polysomnogram revealed an absence of sleep-disordered breathing, the presence of periodic limb movements with frequent awakenings, an absence of EEG abnormalities, and repeated episodes of body rocking.

The patient was diagnosed with restless legs syndrome and sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder because of daytime impairment and a history of injury. He was given supplemental iron treatment for the restless legs syndrome. The family was given reassurance that he did not have a seizure disorder. Treatment options, including a short course of benzodiazepine therapy, were discussed with the family.

At follow-up, the mother reported an improvement in the child’s sleep, including improved sleep onset within 15 minutes and fewer nocturnal awakenings. The patient also reported an improvement in his symptoms of restless legs. His daytime irritability had also improved. He continued to have body rocking, which was of shorter duration and occurred less frequently. The mother was reassured that the body rocking would continue to resolve with increasing age.

Although the exact cause of rhythmic movement disorder is unknown, it has been suggested that it may be a part of normal development. Other suggested etiologies include a kinesthetic drive, tension-releasing maneuver, attention-seeking device, response to restricted activity, a consequence of emotional deprivation, and the result of acute illness (40). Developmental disorders and perinatal risk factors have been reported in association with both sleep-related rhythmic movements and rhythmic movement disorder in children and young adults; when sleep-related rhythmic movements significantly interfere with sleep or affect daytime functioning, potentially resulting in injury, rhythmic movement disorder is diagnosed (51).

A familial history, although uncommon, has been reported (45; 08). Attarian and colleagues reported a multigenerational family in which 50% of the family members had insomnia or insomnia and sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder that persisted into adulthood (08).

The role of genetic factors has been suspected in some cases. Hayward-Koennecke and colleagues reported monozygotic female triplets affected by cystic fibrosis who presented with a rolling subtype of rhythmic movement disorder (30).

No neuropathologic lesion has been described, although an abnormality of the basal ganglia has been suggested. Motor stereotypies generally seem dependent on some kind of basal ganglia circuitry involving the striatum or the substantia nigra (11; 21). Stereotypic behaviors performed by captive and domesticated animals housed in barren environments resemble rhythmic movement disorder and are thought to reflect disinhibition of the behavioral control mechanisms of the dorsal basal ganglia (22). The release of a central pattern generator has also been suggested to account for the occurrence of rhythmic movements in both physiological and pathologic conditions (42). The presence of subcortical central pattern generators has been proposed to account for the similarities in movements observed between frontolimbic epileptic seizures, parasomnias, and sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder (60). In addition, the presence of a central pattern generator in the mesencephalic, pontine, and spinal cord regions has also been suggested to explain the case reports of rhythmic movements seen in cases of idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder (24).

Some authors have proposed different pathogenetic mechanisms for the rhythmic movements seen in NREM versus REM sleep. Manni and colleagues reported the association between sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder and cyclic alternating pattern (CAP) (44). They reported a 9-year-old boy with a history of repetitive, sometimes violent, nocturnal movements since 6 months of age. Video-polysomnographic recording revealed a close association between the rhythmic movements and CAP. In addition, the CAP score at 40% was higher than the mean normative data for children of similar age (33%). Due to the child’s report of nonrestorative sleep, poor daytime function, and occasional mild injury of the head or soft tissues of the face, a trial of clonazepam was conducted. With this treatment, the sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder resolved, and the CAP score was reduced to 26% (44).

Rhythmic movements are very common in infants. At 9 months of age, 59% of infants are observed to have rhythmic movements of some sort, including body rocking (43%), head banging (22%), and head rolling (24%). The overall prevalence of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder at 18 months is 33%, and by 5 years is only 5%. Gender differences have not been demonstrated in most pediatric studies (03; 04); however, male preponderance was reported in adult forms of rhythmic movement disorder (04).

Generally, the behavior ends spontaneously by 4 years of age (40). However, persistence beyond childhood into adolescence and adulthood is recognized and documented (29; 70). In a 2023 paper consisting of a case series of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder diagnosed on video-polysomnography in subjects in a sleep neurologic clinic and of an updated review of all papers published on the topic since the year 2000, Al Sa'idi and colleagues reported sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder in nine patients (two females) 9 to 62 years of age, with associated comorbid primary sleep disorders in five subjects and neurodevelopmental disorders in four (01).

Movements in sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder can be reduced in some individuals by preventing or reducing emotional stress or stressors. In addition, injury may be reduced by creating a safe environment, including padding on the bed.

Even though sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder is easily diagnosed based on clinical history in most cases, a few sleep-related disorders may be misdiagnosed as rhythmic movement disorder. These include seizures, periodic limb movements, self-stimulatory behavior (masturbation), hypnagogic foot tremor, alternating leg movements of sleep, or hypnic jerk (sleep start). When tongue biting is present, or when the movement includes a tonic phase (when muscles are stiff during part of the movement), seizures need to be considered in the differential diagnosis (64). In addition, sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder may be confused with bruxism, thumb sucking, rhythmic sucking of a pacifier, and other such movements. The limb movements seen with periodic limb movement disorder or restless legs syndrome may sometimes appear rhythmic. Patients with restless legs syndrome will usually report discomfort in their body and other classic symptoms of restless legs syndrome. Autoerotic or masturbatory behavior in sleep may appear rhythmic but is primarily focused on the genital area and should not be termed as sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder (55). Hypnagogic foot tremor is a rhythmic movement of the feet occurring every second or so for several minutes (68). It is seen before sleep onset or during light sleep. Alternating leg movements of sleep may represent that same disorder and involve brief contraction of the anterior tibialis in one leg alternating with the other during sleep (13). It is unclear if these two conditions are separate entities or a variant of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder. Sleep starts are brief jerks that occur during sleep-wake transitions and, when recurrent, may appear rhythmic.

Although the movements seen in patients with REM sleep behavior disorder and NREM parasomnias are complex, the associated movements may sometimes appear rhythmic and should also be differentiated from sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder.

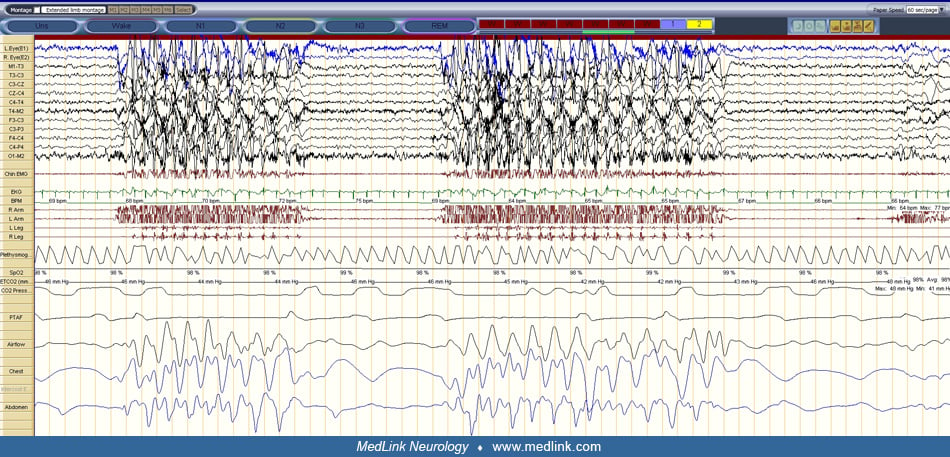

The clinical history and features of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder are typical, and no further work-up is usually needed. However, when epilepsy is suspected video-EEG monitoring should be performed to evaluate for possible seizures. Polysomnography with time-locked video monitoring may also be useful in visualizing and differentiating the different types of sleep-related movements (28).

If injury occurs, standard testing to evaluate for physical injury is indicated. This may include CT scans and x-rays if deemed clinically appropriate.

Young infants or children with sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder require no treatment as the condition usually resolves spontaneously. Parents should be advised that neurologic damage is unlikely and that the child will outgrow the problem. If the condition persists into adolescence and adulthood, treatment may be considered. Both behavioral and pharmacologic therapies have been tried. Behavioral therapies include habit reversal, which consists of immediate detection of the movement followed by feedback for the behavior, such as verbal feedback by night observers or the use of a light or audible alarm attached to the bed (41). Also, because the rhythmic movements are highly conditioned to the sleep-onset process, teaching replacement behaviors such as sleeping on one’s back or mild rocking from side to side as opposed to violent head banging has also been tried (18; 59). Straus and colleagues were successful in treating a 7-year-old girl with head banging by teaching her to repeatedly stop her head movement just before striking the bed and then calmly lying down (57). There is also a case report of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder being treated with hypnosis (54).

Pharmacological therapy has also been successfully tried for this disorder. Most of the evidence is based on case studies (38). Both short-acting benzodiazepines and long-acting benzodiazepines, including clonazepam, have been found beneficial (16; 29; 35; 26). In addition, clonazepam effectively curtailed sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder consisting of multiple types of rhythmic movements seen in the same night in young patients (31; 47). Citalopram and imipramine have also been successfully tried (25; 19; 02; 66). In addition, Etzioni and colleagues reported that 3 weeks of controlled sleep restriction, with hypnotic administration in the first week, resulted in almost complete resolution of the rhythmic movements in six children (20).

Finally, when rhythmic movement disorder is found to be associated with periodic arousal in sleep resulting from obstructive sleep apnea, a trial of continuous positive airway pressure may be worthwhile (15; 23).

To the authors’ knowledge, there are no reported cases of sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder during pregnancy. More common complaints, such as sleep-related leg cramps or pregnancy-related secondary restless legs syndrome, should be considered.

There is a case report of a 10-year-old girl who developed rhythmic movement disorder after outpatient foot surgery (10). When emerging from general anesthesia, she started to develop jerking movements of her arms and torso whenever she drifted off to sleep. The movements initially lasted only several seconds, but as the day progressed, they developed into rhythmic shaking of the upper body and head and lasted several minutes. She was easily arousable during these events and was oriented but was not aware of the events. The symptoms improved slowly over the next several days.

All contributors' financial relationships have been reviewed and mitigated to ensure that this and every other article is free from commercial bias.

Raffaele Manni MD

Dr. Manni of the National Institute of Neurology, IRCCS C Mondino Foundation has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

See Profile

Antonio Culebras MD FAAN FAHA FAASM

Dr. Culebras of SUNY Upstate Medical University at Syracuse has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

See ProfileNearly 3,000 illustrations, including video clips of neurologic disorders.

Every article is reviewed by our esteemed Editorial Board for accuracy and currency.

Full spectrum of neurology in 1,200 comprehensive articles.

Listen to MedLink on the go with Audio versions of each article.

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Epilepsy & Seizures

Jan. 20, 2025

Movement Disorders

Jan. 20, 2025

Sleep Disorders

Jan. 18, 2025

Neuro-Oncology

Jan. 14, 2025

Neuro-Oncology

Jan. 14, 2025

Neuro-Oncology

Jan. 14, 2025

Neuro-Oncology

Jan. 14, 2025

Neuro-Oncology

Jan. 14, 2025